Disney often displayed his innovations at the annual New York World’s Fair. His attractions drew record crowds that spilled out from the waiting areas inside the pavilions and onto the fairgrounds. The implementation of switch-back lines (lines that fold in on themselves instead of remaining straight) allowed more people to be condensed into a smaller area in an efficient and organized fashion. Switch-back lines today can be seen in banks, airports, and of course, Disney theme parks. Disney later took the “waiting in line” concept to an entirely new level with the introduction of interactive lines. These are lines that actually become part of the ride itself. For example, Disney attractions like the Haunted Mansion, Tower of Terror, and Midway Mania (pictured above) all feature unique interactive lines.

Disney was responsible for many hugely influential innovations in his lifetime, some of them even unintentionally. Main Street, USA in Disneyland is widely recognized as the world’s first indoor shopping mall. Shops on either side of the street have openings which allow you to walk from one shop to the next, all under cover, from one end of the street to the other. The design may not have been done with malls in mind, but businesses have certainly taken the idea and run with it.

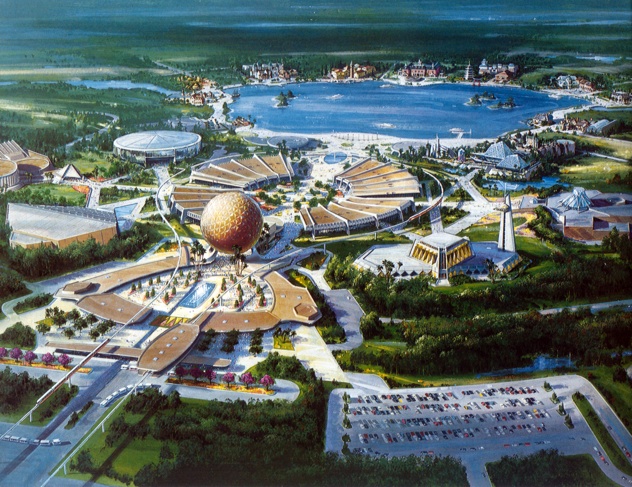

Moving large groups of people quickly and efficiently were some of the main tenets of Epcot (back in the days when Epcot was going to be a model city of the future). Disney pioneered the use of the all-electric PeopleMover system, which was planned to shuttle residents around Epcot. Also on the drawing board was the use of monorails for mass transportation of residents to and from the urban section of the city. Both systems are still in use today. The PeopleMover is located in the Magic Kingdom and actually passes through Space Mountain where a portion of the model of Epcot can be seen. The monorail is located in and around both the Magic Kingdom and Epcot. Disney’s monorail was America’s first daily-operating Monorail system.

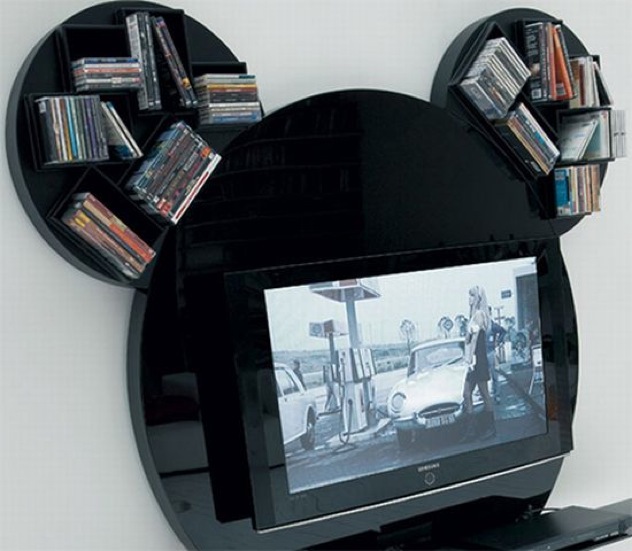

Disney was a trailblazer in merchandising. He understood early on that the right merchandise could become an effective tool to promote Disney movies and TV shows. As soon as Mickey Mouse became popular, Disney manufacturers flooded him with ideas to cash in on the phenomenon. Disney only wanted the best products to bear Mickey’s name and image however. The studio negotiated a 2.5-5 percent royalty on all items, and at the depth of the Great Depression consumers bought hundreds of thousands of items from toys and ice cream cones to the famous Mickey Mouse watches. In the early 50’s the Disneyland television program aired the show Davy Crockett. A trade embargo with China led to surpluses of raccoon skins and inspired Disney to negotiate a deal for coonskin hats like the one worn by Crockett on the show. Demand exceeded expectations and the hats sold by the millions. Composer George Burns put together a song titled “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” for the show. The track quickly became a hit, selling ten million copies and spending a month at #1. Even though we take merchandising for granted these days, in Disney’s time these fresh innovations helped change American entertainment.

Long before a television sat in every living room, Disney understood their power. During the early stages of planning Disneyland, Walt and his brother Roy knew they needed money to help fund such an ambitious project. Roy traveled to New York to meet with network executives to discuss TV’s ability to finance and promote the park. ABC agreed to a weekly Disney series. The series debuted in 1954 with major success. The studio used the series to hype the theme park and promote Disney films. Walt insisted on filming as many segments as possible in color, even though most televisions still used black and white, because he believed color would become the new standard. A few years later, he moved his show to NBC, where the entire program was broadcast in color and retitled “Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color.” With this 1961 television series, Disney Studios became the first ever to provide regular color programming for television. Disney clearly saw the value of the then infantile medium of television. He was aware of the power of promotion through TV and he used it to connect with the public in an entirely new way.

The 1965 New York World’s Fair saw Disney successfully introduce a number of never-before-seen ride innovations. Traditionally, theme park attractions included outdoor rides and perhaps a fun house / haunted house walkthrough. Disney radically changed this model, creating the standard for what we now consider “theme park rides.” When Disney was working on the “It’s a Small World” attraction, it was planned to be a walk-through attraction. Disney realized however, that he couldn’t handle enough people using a walk-through format. So, the attraction became a boat ride, where flat-bottomed boats were gently pushed along by underwater jets. The ride system was so successful that the Pirates of the Caribbean, originally meant to be a walk-through, was changed to a more realistic boat ride. Rides like Matterhorn Mountain, the world’s first enclosed steel roller coaster, and “Soarin” in Epcot, also fall into the parameters of “fitting into the theme of the show.” The Omni-mover ride system, where ride vehicles glide along on a continuously moving track, was developed for the World’s Fair and was used on the Ford Magic Skyway attraction. Rides like the Haunted Mansion in the Magic Kingdom (the fabled doom buggies) and Spaceship Earth in Epcot still employ the system.

Walt Disney dreamed of creating the first entertainment enterprise where children and parents could have fun together. While we may take such a concept for granted today, the idea was truly novel back in the mid-20th century. Traditionally, amusement parks only catered to children, leaving tag along parents with nothing to do. Walt envisioned a place where parents and children could share fun experiences with each other. Disneyland, which opened on July 17, 1955, was that place. Disney also surrounded his innovative park with an earthen barrier to insulate his guests from the intrusions of the outside world and place them in a reassuring atmosphere. Disney emphasized that the parks are about reassurance, that the world can be OK, that you can talk to a stranger in a public place, and that a public place can be clean.

Hastened by Disney’s participation in the World’s Fair, audio-animatronics became one of the most significant breakthroughs in the history of theme park entertainment. Attractions like The Carousel of Progress, Ford’s Magic Skyway, and Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln all featured Disney’s never-before-seen robots. The audio-animatronic figures moved and talked, grunted and gesticulated like real, live beings. It was a new toy for Disney’s creative staff, and a new way to tell stories in three-dimensional fashion. While the Carousel of Progress and the Magic Skyway featured rather anonymous characters, the Lincoln figure recreated the famed US president in jaw dropping fashion. It turned out, in hindsight, to be a radical machine; the first time the world was ever going to see a really believable animated figure. The latest and most sophisticated audio-animatronic figures continue to play prominent roles throughout the Disney entertainment world.

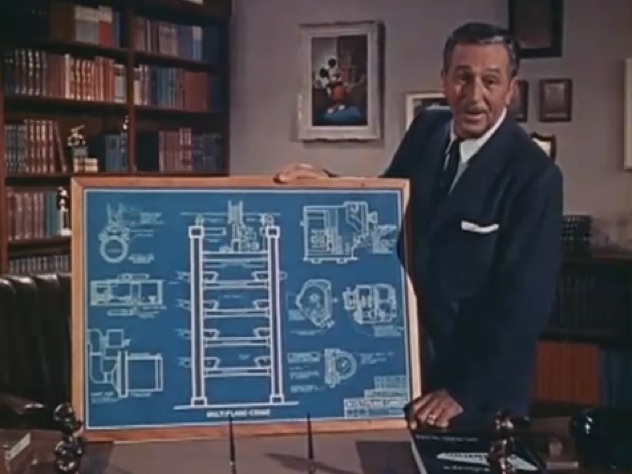

It is hard to imagine any aspect of animation that was not influenced by Walt. He created the first cartoon to successfully synchronize sound and picture (Steamboat Willie, 1928). He was responsible for the first feature length animated film (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, 1937). He pioneered the use of the Circle Vision filming technique, which allowed him to shoot and present movies in 360 degrees, surrounding the audience. He was even the first to develop an optical printer that could combine live-action and animation together (The Three Caballeros, 1945). And as if this wasn’t enough, perhaps his largest contribution to the world of animation was his invention of the multi-plane camera, pictured above (Patent No. 2,201,689). The multi-plane camera is a special motion picture camera which allowed Disney to transform flat, one-dimensional animation into layered shots with depth and movement. Various parts of the artwork layers are left transparent, to allow other layers to be seen behind them. The movements are calculated and photographed frame-by-frame, with the result being an illusion of depth by having several layers of artwork moving at different speeds. It transformed animation in much the same way that computer graphics did years later.

EPCOT stands for “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow.” No one can say just when the idea of creating a model city of the future occurred to Walt Disney, but as early as 1964, operating in secrecy, Disney began planning a true city of the future; a development combining the latest technologies and materials with time-tested concepts about livable communities. Epcot’s radial design surrounded a high-density urban core with low-density neighborhoods; at its center was a 50-acre downtown area housing hotels, apartments, convention centers and offices, and shopping and entertainment venues. Towering above was the spire of a cosmopolitan 30-story hotel, providing guests with a panoramic view of Walt’s sleek metropolis. Transportation was important to Walt’s Epcot; the layout of the city was designed to discourage car use. Facilities could be accessed via PeopleMover, or, for those who did drive, an intricate system of roads allowed motorists to travel around the city without gridlock or even stoplights. An enclosed downtown Transportation Lobby enabled transfers between the city’s PeopleMover system and monorails linking to other parts of the planned Disney World development. Walt said Epcot would constantly be updated to project a vision of “optimum patterns of urban living” 25 years in the future, and was designed to be a dynamic environment that would “always be introducing and testing and demonstrating new materials and new systems.” Sadly, Walt Disney died in 1966, before Epcot could be realized. Walt’s brother Roy decided to suspend master planning in favor of focusing all efforts on finishing the Magic Kingdom. The vision of Epcot still lives on today however, as one of four theme parks in Walt Disney World. Ross is a patent agent and long time Listverse fan.