Scattered across the globe, fossils are traces of organisms from a past geologic age that have been embedded and preserved in the Earth’s crust. But despite fossils’ wide range, the Sahara Desert contains many of the oldest, biggest, and most unusual fossils ever found. These ancient relics grant insight into the history of our planet and many creatures, including humans.

10 Giant Catfish

An ancient relative of the well-known catfish was plucked from the sands of Egypt in 2017. The new species was named Qarmoutus hitanensis and is believed to have lived roughly 37 million years ago. At about 2 meters (6.5 ft) long, this specimen would be on the upper end of the catfish size scale. Qarmoutus hitanensis represents an entirely new genus and species, making it an intriguing early branch on the catfish family tree. According to John Lundberg from Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences, the ancient fossil is more like the modern-day catfish than one would expect. “Even though the fossil is relatively old in the way we ordinarily think of ages in millions of years, it is still essentially anatomically modern and directly comparable to living catfishes,” said Lundberg. “It’s one of the best preserved and oldest of its family.”[1]

9 Massive Crocodile

In 2014, paleontologists discovered the remains of one of the biggest crocodiles ever found. Named Machimosaurus rex, this prehistoric beast was twice the size of any crocodiles seen today. It would have weighed at least 2,993 kilograms (6,600 lb) and been around 9.8 meters (32 ft) long. The fossil was buried in Tunisia on the edge of the Sahara Desert. The Machimosaurus rex was likely a top predator in what was then an ocean that separated Africa from Europe about 130 million years ago. “The skull itself is as big as I am,” explained Federico Fanti from the University of Bologna who was part of the team that made the discovery. “Just the skull is more than five feet long. It’s a massive crocodile. He was so big and so powerful that it was absolutely at the top of the food chain.”[2] Besides its size, this find is also significant because these crocodiles were believed to have died out in a mass extinction event between the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods about 150 million years ago. The discovery suggests that the extinction event was not as widespread as some paleontologists thought. “Everyone thought this group of crocodiles went extinct in the Jurassic, but we found it well into the Cretaceous,” said Fanti. “We simply extended the temporal range of the animals. Twenty million years is a lot of time.”

8 Spinosaurus Fossil

Spinosaurus is well-known in the scientific community as one of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs to have ever lived. But one giant fossil unearthed in 2014 in the Sahara Desert has given scientists an unprecedented look at the creature. The 95-million-year-old remains confirmed a theory that this is the first swimming dinosaur that we know of. Scientists say that the beast had flat, paddle-like feet and nostrils on top of its crocodilian head that would allow it to submerge with ease. Other ancient creatures that lived in the water, such as the plesiosaur and mosasaur, were marine reptiles rather than dinosaurs, making Spinosaurus the only known semiaquatic dinosaur. Nizar Ibrahim, a paleontologist from the University of Chicago, said: It is a really bizarre dinosaur—there’s no real blueprint for it. It has a long neck, a long trunk, a long tail, [a 2.13-meter (7 ft) sail] on its back, and a snout like a crocodile. And when we look at the body proportions, the animal was clearly not as agile on land as other dinosaurs were, so I think it spent a substantial amount of time in the water. Although the first Spinosaurus remains were discovered around 100 years ago in Egypt, they were destroyed during World War II when an Allied bomb hit a museum in Munich, Germany. A few drawings of the fossil survived, but only fragments of Spinosaurus bones were found ever since. The new fossil extracted in eastern Morocco has provided scientists with a more detailed look at the dinosaur. “For the very first time, we can piece together the information we have from the drawings of the old skeleton, the fragments of bones, and now this new fossil, and reconstruct this dinosaur,” said Ibrahim. “The hind limbs were shorter than in other predatory dinosaurs, the foot claws were quite wide, and the feet almost paddle-shaped.” As time went on, the scientists continued to find more proof of the creature’s aquatic life. Ibrahim noted: The snout is very similar to that of fish-eating crocodiles, with interlocking cone-shaped teeth. And even the bones look more like those of aquatic animals than of other dinosaurs. They are very dense and that is something you see in animals like penguins or sea cows, and that is important for buoyancy in the water.[3]

7 Legged Whales

Wadi Al-Hitan (“Whale Valley”) is a paleontological site in the Al Fayyum Governorate of Egypt around 150 kilometers (93.2 mi) southwest of Cairo. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005 after hundreds of amazing fossils were discovered in the area. The valley got its name due to an incredibly high concentration of high-quality marine fossils. The most important discovery at the site is believed to be an extinct suborder of whales called Archaeoceti. These fossils represent a key piece in the story of evolution—the emergence of the whale as an ocean-going mammal from a previous life as a land-based creature. The first whale skeletons were discovered in 1902. Initially, the site attracted relatively little interest because it was difficult to reach. That changed when four-wheel-drive vehicles became more readily available in the 1980s. The largest skeleton found reached 21 meters (69 ft) in length, with well-developed five-fingered flippers on the forelimbs and the unexpected presence of hind legs, feet, and toes not known previously in any Archaeoceti. Besides whales, hundreds of other marine creatures such as crocodiles, turtles, sharks, and rays have been uncovered. Some fossils are so well-preserved that their stomach contents are still intact. The incredible quality and quantity of the remains make it possible for scientists to reconstruct the surrounding environmental and ecological conditions of the time.[4]

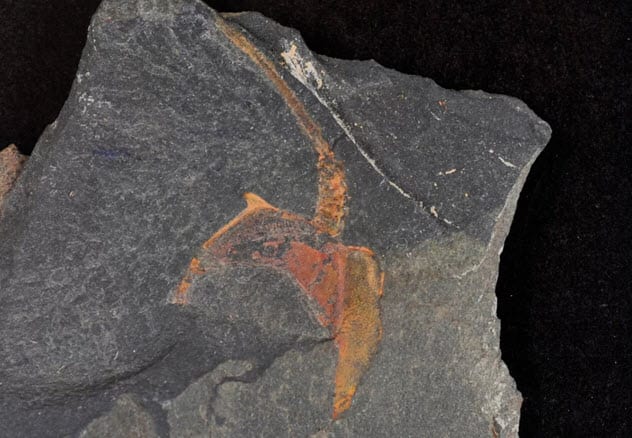

6 480-Million-Year-Old Mystery Creature

A mysterious creature that lived hundreds of millions of years ago was hotly debated by scientists for 150 years since its initial discovery in the 1850s. The mystery was finally unraveled in early 2019 when new stunningly detailed fossils discovered in Morocco allowed paleontologists to identify the bizarre creature. These life-forms, known as stylophorans, looked like flat armored wall decorations with a long arm poking off their sides. Previously, scientists were not even sure if they fit in the animal family tree. However, the new study revealed that the creatures were echinoderms—ancient relatives of animals such as starfish, sea lilies, sea urchins, feather stars, and sea cucumbers. Lead researcher Bertrand Lefebvre said that the findings were possible thanks to fossils with “unequivocal evidence for exceptionally preserved soft parts, both in the appendage and in the body of stylophorans.” Although the incredible fossils were unearthed along the edge of the Sahara Desert in 2014, researchers didn’t immediately realize that some of the 450 excavated stylophoran specimens included preserved soft tissues. “This discovery is of particular importance because it brings to an end a 150-year-old debate about the position of these bizarre-looking fossils in the tree of life,” Lefebvre said.[5]

5 World’s Oldest Biological Color

A team of scientists discovered the oldest color in the geological record beneath the Sahara Desert in 2018. The excavated fossils appeared to have a variety of colors. Originally green, the fossils became bloodred to deep purple in their concentrated form. However, once diluted, the fossils revealed a bright pink pigment in an oil form. This bright pink pigment is believed to be 1.1 billion years old. According to Nur Gueneli from The Australian National University, the ancient pigment was extracted from marine black shales of the Taoudeni Basin in Mauritania, West Africa. Gueneli said that the pigment resulted from molecular fossils of chlorophyll that were processed by ancient photosynthetic organisms that used to rule the oceans. “Of course, you might say that everything has some color,” said senior lead researcher Jochen Brocks. He compared the discovery to finding an ancient T. rex bone. “It would also have a color, it would be gray or brown, but it would tell you nothing about what kind of skin color a T. rex had.” Brocks continued, “If you would now find preserved, fossilized skin of a T. rex, so that skin still has the original color of a T. rex, say it’s blue or green, that would be amazing.” Then he concluded, “That’s in principle what we’ve discovered . . . only 10 times older than the typical T. rex. And the molecules we’ve found were not from a large creature but microscopic organisms because animals didn’t exist at that time. That’s the amazing thing.”[6]

4 New Pterosaur And Unknown Sauropod

The discovery of a new dinosaur species is a rare occurrence, but discovering two new species in one expedition is any paleontologist’s dream. One team of paleontologists made that dream a reality in 2008 when they unearthed a new pterosaur and a previously unknown sauropod dinosaur in the Sahara Desert. The pterosaur was identified by a large fragment of the flying reptile’s beak, while the sauropod was represented by a long bone measuring more than 0.9 meters (3 ft) long. It indicated an herbivore, nearly 20 meters (65 ft) in length. Both these extinct giants would have lived almost 100 million years ago. Pterosaur remains are particularly uncommon because their light and flimsy bones, optimized for flight, are rarely found in a well-preserved state. Nizar Ibrahim, then a graduate student at University College Dublin who led the expedition, stated: “Most pterosaur discoveries are just fragments of teeth and bone, so it was thrilling to find a large part of a beak, and this was enough to tell us we probably have a new species.”[7]

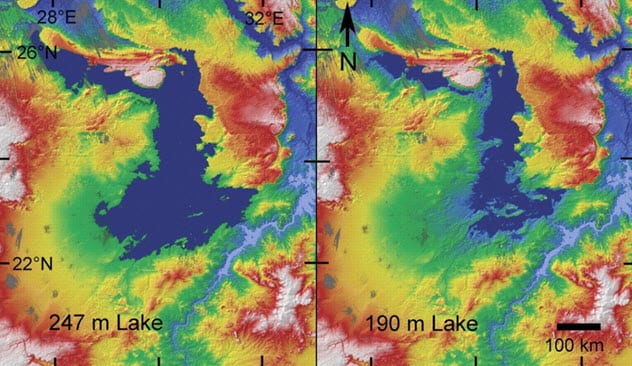

3 Fish Fossils Lead To Ancient Mega-Lake Discovery

In 2010, scientists discovered evidence of a prehistoric mega-lake that had formed beneath the sands of the Sahara around 250,000 years ago when the Nile River flooded the eastern Sahara. At its highest level, the lake covered over 108,780 square kilometers (42,000 mi2) and reached a height of 247 meters (810 ft) above sea level. Scientists estimate that the Nile once flooded the entire Kiseiba-Tushka depression of Egypt and created the massive lake. Deposits of fish fossils found about 402 kilometers (250 mi) west of the Nile played an important part in the discovery and were used as a sea-level marker of the lake’s highest shoreline. Researchers also used radar data of Egypt taken by the Space Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Geologists pieced together the profile of the mega-lake by using images of windblown sediments, sediments produced by running water, and bedrock beneath the desert sands.[8] A different set of archaeological sites near Bir Kiseiba, 150 kilometers (93 mi) west of the Nile, suggests a second level of the lake at 190 meters (623 ft) above sea level. The lower-level lake is believed to have covered 48,174 square kilometers (18,600 mi2). It adds to growing evidence of numerous Early and Middle Pleistocene lakes across North Africa, which could have supported human migration patterns.

2 Holy Grail Of Dinosaur Fossils

In 2013, a team of scientists from the Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology (MUVP) unearthed what has been described as the holy grail of dinosaur fossils—a near-complete, school-bus-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous era. The well-preserved remains belong to a titanosaurian sauropod, a type of long-necked, herbivorous dinosaur that lived around 94 to 66 million years ago. The dinosaur, dubbed Mansourasaurus shahinae gen, was discovered in the Quseir formations of the Dakhla Oasis in Egypt’s Western Desert. It was the sixth and youngest dinosaur to be discovered in Egypt. According to Hesham Sallam, lead author of the study, the fossils represent the most complete remains belonging to a dinosaur of this era in the entire African continent. “The discovery and extraction of Mansourasaurus was such an amazing experience for the MUVP team,” said Sallam. “It was thrilling for my students to uncover bone after bone, as each new element we recovered helped to reveal who this giant dinosaur was.”[9]

1 Oldest Fossils Of Homo sapiens

Miners in Morocco dug up a few skull pieces at a site called Jebel Irhoud in 1961. A few more bones were found in later digs along with flint blades and charcoal, indicating the use of a campfire. Researchers initially estimated the remains to be 40,000 years old until a paleoanthropologist named Jean-Jacques Hublin inspected one jawbone in the 1980s. While the teeth were similar to those of living humans, the jawbone’s shape seemed strangely primitive. “It did not make sense,” Dr. Hublin recalled in an interview. In 2004, Dr. Hublin and his colleagues started working through layers of rocks on a desert hillside at Jebel Irhoud. Since then, they have found many fossils including skull bones from five individuals who had all died around the same time. The scientists also discovered important flint blades in the same sedimentary layer as the skulls. People of Jebel Irhoud probably lit fires to cook food, heating discarded blades buried in the ground below. This made it possible to use the flints as historical clocks. Through a method called thermoluminescence, Dr. Hublin and his colleagues calculated that the blades were burned roughly 300,000 years ago. As the skulls were discovered in the same rock layer, they must have been around the same age. Despite their old age, anatomical details showed that the teeth and jaws belonged to Homo sapiens, not another hominin group such as the Neanderthals.[10] However, the researcher’s claim is controversial. Anthropologists are still debating what exact physical features distinguish modern humans from our ancestors. The previous oldest-known bones widely recognized as Homo sapiens are around 200,000 years old. The new discovery pushes the date of the emergence of our species back another 100,000 years.