10Oriens Rises

In October 2013, the 1-meter (3 ft), lead-lined coffin of a Roman child was discovered by a treasure hunter with a metal detector in a Leicestershire field. So as not to refer to the child as “it,” the public voted to call her “Oriens,” which means “to rise (as the Sun).” It’s believed that Oriens was buried around the third or fourth century. We don’t know her age yet, but bangles found with the child suggest she’s a girl. Oriens must have come from a wealthy or high-status family to have had a lead coffin, which was rare in the Roman world, especially for a child. Most children of that time were buried in the ground with only a shroud. Only a few bone fragments remain of Oriens. Even so, archaeologists can piece together some details of her story, including the society in which she lived. They learned a lot just from some resins in her coffin. As Stuart Palmer from Archaeology Warwickshire explains, “The presence of frankincense, olive oil, and pistachio nut resin in the soil found in Oriens’ coffin places the child as one of only a very small number of Roman burials that indicate a high-status individual, buried using very expensive Mediterranean and Middle-Eastern burial customs.” These resins masked the odor of a decaying body while funeral rites were performed and eased her transition to the afterlife. From a societal standpoint, it also shows that residents of Roman Britain continued to use continental burial rites that required them to import resins from the Middle East.

9Secrets Of A Child Singing Star

Almost 3,000 years ago, seven-year-old Tjayasetimu was a singing star in the temple choir that performed for the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Although some of the little girl’s secrets were taken to the grave, curators at the British Museum, where her mummy was exhibited in 2014, were able to discover some telling details about her. We don’t know exactly where she lived or worked because the British Museum bought the mummy from a dealer in 1888. But Tjayasetimu’s body was incredibly well preserved. In the 1970s, a restoration project revealed hieroglyphics and paintings under the blackened oil that covered her bandages. The inscription gave her name and job title. Tjayasetimu’s name, which means “the goddess Isis shall seize them,” protects against evil spirits. Her job, “singer of the interior,” was an elevated position in the temple for the god Amun. No one knows if she received that job because of her voice or family connections. But she must have been important to be mummified with a golden mask placed over her face. In 2013, CT scans revealed that that her body, including her face and shoulder-length hair, was still well preserved. With no signs of long-term illness or trauma, she is believed to have died from a short illness like cholera.

8The Mystery Of The Sewer Babies

In the Roman Empire, infanticide was commonly practiced to limit family size because no reliable birth control methods were available. It also helped to conserve scarce resources and improve the lives of other family members. Babies under six months old were not considered human in Roman society. Even so, a particularly ghastly discovery was made in 1988 at Ashkelon on Israel’s southern coast. There, archaeologists found a mass grave of almost 100 infants in the ancient sewer beneath the site of a Roman bathhouse. With most of the bones intact from each area of their skeletons, scientists believe the babies were tossed into the drain shortly after death. Given their similar ages and no evidence of disease, the cause of death is almost surely infanticide. Although Romans preferred male children, researchers couldn’t find evidence that Romans deliberately killed more female than male infants on a consistent basis. That was true at the Ashkelon bathhouse as well. Some archaeologists believe the bathhouse also served as a brothel. They theorize that the infants were the unwanted children of prostitutes who worked there. Some female infants may have been spared so they could become courtesans as they grew older. Although both men and women were prostitutes in the Roman Empire, some historians believe that women were more in demand.

7The Extraordinary Child Metal Workers

Around 4,000 years ago in prehistoric Britain, children were tasked with decorating jewelry and weapons with tiny gold studs as thin as human hairs. In some cases, the studs were placed at over 1,000 per square centimeter (6,500/in2) of wood. Scientists discovered this after fragments from the ornate handle of a wooden dagger were excavated in the early 1800s from the Bush Barrow burial mound near Stonehenge. The work is so detailed that it’s hard to see with the naked eye. As a result, scientists deduced that teenagers and children as young as 10 must have been responsible for the extraordinary craftsmanship on the dagger handle. Without a magnifying glass, normal adult eyesight wouldn’t be sharp enough. As early as age 21, an adult’s eyesight begins to deteriorate. Although these children would have used simple tools, they had a sophisticated grasp of design and geometry. But their beautiful handiwork came at a high personal price. Their eyesight would have been damaged quickly, with the possibility of extreme myopathy by age 15 or even partial blindness by age 20. That would have rendered them unfit for other work, forcing them to rely on their communities for support.

6The Surprisingly Good Parents

Believing that Neanderthals have been misjudged, some archaeologists from the University of York want to rewrite the story of these prehistoric people. Until recently, the prevailing viewpoint has been that Neanderthal children lived dangerous, difficult, and short lives. But the York team reached a different conclusion after studying the social and cultural evidence at Neanderthal sites throughout Europe. “The reputation of the Neanderthals is changing,” said Dr. Penny Spikins, the lead researcher. “Partly, that’s because they have been shown to have bred with us—and that implies similarities to us—but also because of the emerging evidence of how they lived. There is a critical distinction to be made between a harsh childhood and a childhood lived in a harsh environment.” Spikins thinks that Neanderthal children experienced strong bonds within close-knit families. She also believes they were schooled in crafting tools. At two sites in different countries, the York team discovered stones that were well crafted among others that were roughly chipped, as if children were learning from adults how to make hand axes. Although there isn’t any hard evidence to prove it, Spikins feels that these prehistoric youngsters played peek-a-boo because great apes and humans play this type of game. When studying the graves of Neanderthal infants and children, Spikins found that Neanderthal parents buried their young with great care. Artifacts were more likely to be discovered with the skeletons of children than adults. The York team claims there’s also evidence that Neanderthal parents cared for their sick or injured children, sometimes for years.

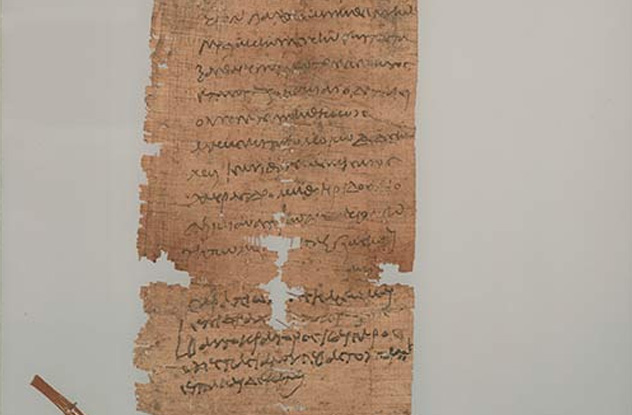

5The Roman Egypt Boy Scouts

To learn about ancient childhood in the town of Oxyrhynchos in Roman Egypt, historians are examining about 7,500 documents believed to be from the sixth century and earlier. With over 25,000 residents, Oxyrhynchos functioned as the Roman administrative center for its area. The town was also a powerhouse for the weaving industry in Egypt. From papyri excavated from an Oxyrhynchos garbage dump a century ago, historians found that Roman Egypt had its own version of the Boy Scouts, a youth organization known as a “gymnasium” where young men were taught to become good citizens. Boys from free-born Egyptian, Greek, and Roman families were qualified to join. Back then, that demographic was wealthy, limiting membership in the gymnasium to boys from about 10–25 percent of the town’s families. For the boys who were eligible, enrollment in the gymnasium represented the start of their transition to adulthood. Men became full adults when they got married in their early twenties. Women, who usually married in their late teenage years, prepared for their roles by working in their homes. Boys of free-born citizens who didn’t qualify for the gymnasium might begin working as preteens, possibly as apprentices under contract for two to four years. Many of the contracts were in the weaving industry. The historians did find one apprenticeship contract for a girl. But they believe her situation was unique in that she was an orphan who needed to pay off her late father’s debts. Slave children were able to have the same types of apprenticeship contracts as free-born boys. But unlike free-born boys, who lived with their families, slave children could be sold. They would live with their owners or masters, even if that separated the children from their parents. Documents revealed that some slave children were sold at just two years old.

4The Mystery Of The Moose Geoglyph

In this story, our discovery of the past came from our curiosity about the future. Images taken from space in 2011 revealed a giant moose geoglyph in the Ural Mountains that’s believed to predate the famous Nazca Lines in Peru by thousands of years. The type of stonework, known as “lithic chipping,” suggests that this structure may have been built as long ago as 3000 or 4000 B.C. The structure is around 275 meters (900 ft) long with two antlers, four legs, and a long muzzle. Facing north, the geoglyph could have been seen from a nearby ridge in prehistoric times as a shiny, white figure against a green grass background. Currently, it’s coated with soil. Excavators have been amazed by the elaborate construction. “The hoof is made of small crushed stones and clay,” explained Stanislav Grigoriev of the Russian Academy of Sciences. “It seems to me there were very low walls and narrow passages among them. The same situation in the area of a muzzle: crushed stones and clay, four small broad walls, and three passages.” Researchers also uncovered evidence of two fireplaces at the site, each used just once. They believe these fireplaces may have been used in an important ritual. But there are so many unanswered questions, such as who built this geoglyph and why. There’s no archaeological proof of a culture advanced enough to build such a structure at that time in this region. But the researchers think their most interesting discovery concerns children. Excavators found over 150 tools at the site, 2–17 centimeters (1–7 in) long. They believe that children, working alongside the adults in a community project, helped to build the moose geoglyph. It doesn’t appear to be child slave labor but rather a joint effort with shared values to achieve an important goal.

3The Children Of The Clouds

We know very little about the Chachapoya and their children because they left no written language. But Spanish documents of the 1500s portray them as fierce warriors. Pedro Cieza de Leon, who chronicled the history of Peru, also described their appearance: “They are the whitest and most handsome of all the people that I have seen in Indies, and their wives were so beautiful that because of their gentleness, many of them deserved to be the Incas’ wives and to also be taken to the Sun Temple.” But these warriors of the clouds did leave one remnant of their culture: their mummified dead, left in fascinatingly strange sarcophagi placed on high ledges overlooking the valleys below. The clay coffins were placed upright and decorated to look like people with paint, feathered tunics, jewelry, and even trophy skulls. But no one knows why the children were buried in their own cemetery, separate from the adults. It’s also unclear why all the small sarcophagi are facing west, which is not normal for a Chachapoya cemetery.

2Gifts For The Lake Gods

Ancient villages from the Bronze Age were scattered around the Alpine lakes of Germany and Switzerland. When some of these areas were excavated in the 1970s and 1980s, archaeologists found over 160 houses 2,600–3,800 years old. These lakefront homes often flooded. To escape the rising waters, lake dwellers would move to dry land. When conditions improved, they’d return to the lakefronts. But these lake dwellers did adapt their lakefront properties for the flooding threat. First, they built their houses on stilts or strong foundations of wood. Second, they enclosed their houses with wooden fences. Third, they surrounded their villages at the edges of the fences with children’s skulls and skeletons. According to archaeologists, these skulls may have been gifts for the lake gods to prevent flooding. Some of the skulls revealed head trauma from clubs or axes. But researchers don’t believe the children were live sacrifices. They believe the kids died a lot earlier, perhaps in warfare, and then were offered to the gods later. At one site, these children, most of whom were younger than 10 years old, were buried at the high-water mark of a flood. But researchers haven’t found the graves of most of the lake dwellers, so they don’t know how a typical burial looks.

1The Infant Who Waits For Eternity

Over 40 years ago, two brothers were hunting in Greenland when they stumbled upon the grave sites of 500-year-old mummies, naturally preserved by the Arctic environment, from the old Inuit settlement of Qilakitsoq. Beneath an outcrop of rock, two separate graves contained eight bodies in all—six women and two young children—each of whom were dressed for hunting. Inuit beliefs at that time required their people to be ready to hunt even after they died. The “Greenland Mummies,” as they’re called, revealed a lot of information about the people’s lifestyles but still left us with many questions. Archaeologists established familial relationships between some of the group. But they weren’t buried according to family lines, which is the first mystery. They were also buried without men, which is another mystery because it’s against Inuit custom. All but one of the women had tattoos, which was fashionable at that time. They had all been well fed before their deaths, with most of their diet coming from the sea. The conditions of their bodies revealed that the women worked with animal skins and sinew. The causes of death appeared to be illness for the older child and two of the women. But it wasn’t clear how the other adults died or if they died at the same time. But it’s the youngest child, the six-month-old baby boy, who has the most poignant story. He appears to have been buried alive, his face upturned as though waiting for the mother who would never reach for him again. The custom of the Inuit at that time was to bury a child alive or suffocate him if another woman wasn’t available to care for him after his mother’s death. By burying the child with his mother, it was believed that they would travel together to the afterlife.