Crispin Andrews talked to Peter McAllister to find out just who could beat whom in today’s sports scene. Here’s what he found out:

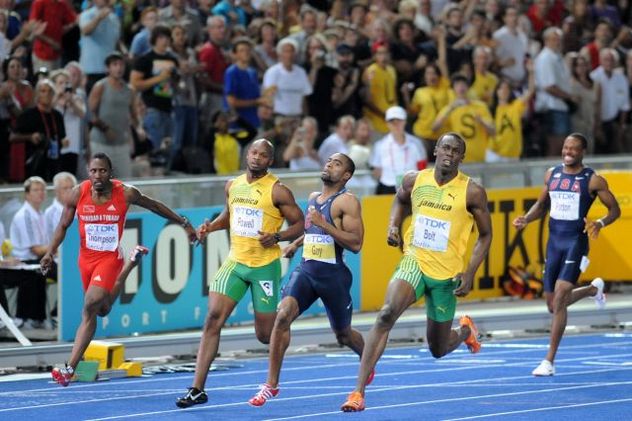

10Usain Bolt vs. Ancient Australians

Usain Bolt ran 100 meters (328 ft) in 9.69 seconds to break the world record at the Beijing Olympics. That’s 42 kilometers per hour (26 mph) for the world’s fastest man. But 20,000-year-old fossilized tracks from Australia show that, back then, ordinary people could manage 37 kilometers per hour (23 mph)—running in soft mud, barefoot. With spikes, a running track, and training, they’d have managed speeds of up to 45 kilometers per hour (28 mph). These ancient Aussies had long limbs and robust leg bones that were 40 percent denser and stronger than those of modern humans. Being nomadic hunters who had to catch their own food, they had a need for speed. Kangaroos and emus were no slouches when running for their lives. Fossilized footprints are extremely rare, and the ones discovered are unlikely to have been left by prehistoric Australia’s fastest runner. The average modern human can run 24 kilometers per hour (15 mph), which is 18 kilometers per hour (11 mph) slower than Bolt. Let’s say that the ancient tracks were left by a runner of average speed. The Pleistocene Aussie equivalent of Usain Bolt would have reached speeds of 63 kilometers per hour (39 mph).

9Samuel Wanjiru vs. Native Americans

Kenyan runner Samuel Wanjiru broke the Olympic marathon record in Beijing in 2008, when he ran it in 2 hours, 6 minutes, and 32 seconds. Had a Mojave Native American from the late 19th century been in the field, Wanjiru would have most definitely been celebrating silver. Back then, the Mojave played a game called kickball. They’d run through the desert all day along the Colorado River, kicking a wooden ball in front of them. By playing this game, an average Mojave expended 17,000 calories of effort in a single day, almost twice the amount lost by riders in the Tour de France. One Mojave man is said to have run 322 kilometers (200 mi) in 24 hours. Greek athlete Yiannis Kouros holds the world record for 24-hour running. In 1997, he managed only 304 kilometers (189 mi)—and he was running in spikes, on a track, and didn’t have to watch out for wolves and rattlesnakes.

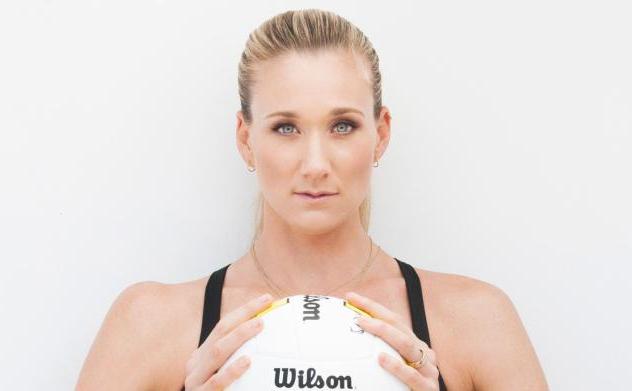

8Kerri Walsh Jennings vs. Pleistocene Aborigines

The Pleistocene Aborigines would have also made great volleyball players. And not just for their Usain Bolt–like speed or their gangly physique that basketball players and fast cricket bowlers would have loved. No, these prehistoric Aussies would have had yet another advantage in a game of volleyball: long arms. On average, they had an extra 10 centimeters (4 in) at the wrist. For a volleyball player, like Kerri Walsh Jennings, long arms are a must. Serve underhand, and those long arms create more speed to propel the ball over the net with power, accuracy, and grace. Longer arms place more force on the server’s elbow and shoulder joints. More force on the joints transfers to a faster serve. Serve overhand, and long arms produce faster speed, which reduces the amount of time the ball spends in the air. Long arms also mean a longer reach, which is crucial for returning opposition serves.

7Olympic Rowers vs. Athenian Oarsmen

If you think today’s Olympic rowers are the best there have ever been, think again. Olympic rowers might be able to move their boats through the water quicker than any previous Olympians. But 2,500 years ago, oarsmen who could beat any modern-day rower were a dime a dozen. In 427 B.C., an Athenian warship, called a “trireme,” managed the 340-kilometer (211 mi) voyage to Lesbos in 24 hours. When modern-day rowers had a go in a reconstructed trireme, they could only manage that speed for a few seconds. Over distance, their top speed was 9 kilometers per hour (5.6 mph). According to one ancient writer, even a moderate Athenian crew could top that. At that time, Athens had 200 triremes and 34,000 oarsmen. After measuring their metabolic rates, scientists concluded that sustained speeds of 14 kilometers per hour (8.7 mph) were beyond the aerobic capacity of modern-day rowers. Athenian rowers, they deduced, must have had a greater built-in capacity for aerobic exercise.

6Wladimir Klitschko vs. Australopithecus

Wladimir Klitschko might look pretty mean—and he certainly is—but the multi-time world heavyweight boxing champion would have come out second best to our earliest ancestor. And that’s despite the fact that the tiny Australopithecus was, on average, a whole 60 centimeters (2’0″) shorter than Klitschko. It’s all about punch force. Chimpanzees have similar physiology to Australopithecus, and they have four times as much muscle strength as humans. They are known to deadlift 272 kilograms (600 lb), and one female chimp has been recorded pulling 572 kilograms (1,261 lb) with one hand. Get into the boxing ring with a chimp, and the chimp wouldn’t need to knock you out; it would just throw you over the top rope. Australopithecus were fast and agile, too. They would have gotten their best shots in while Marciano and Klitschko, lumbering heavyweights by comparison, staggered to defeat.

5Jan Zelezny vs. Ancient Greeks

Matthias de Zordo might sound like a B movie villain from the ’60s, but the 24-year-old German is, in fact, the former world javelin champion. Although his 86.27-meter (283 ft) throw was way short of Jan Zelezny’s 1996 world record of 98.48 meters (323.1 ft). But not even the great Czech, Zelezny, could have matched the ancient Greeks when it came to javelin throwing. The earliest Olympic champions threw over 150 meters (492 ft). Although, to be fair to their modern-day successors, they did use lighter javelins and had a leather throwing thong that added an extra 10–25 percent to the throw. In the early 19th century, Australian aboriginal men of the Dalleburra tribe could throw their hardwood spears 110 meters (361 ft), unaided. British sports educator, Lieutenant Colonel F. A. M. Webster—himself a national championship–winning javelin thrower—reported that in the early 1900s, Turkana men of East Africa regularly outthrew him by meters using their traditional spears.

4Viktor Ruban vs. Mongol Archers

To win gold in Beijing, Ukrainian archer Viktor Ruban shot five of his 12 arrows into the bull’s-eye. And that’s from 70 meters (230 ft). Back when archery meant life or death, Genghis Khan’s warriors could hit a tiny red flag at 150 meters (492 ft). One of the Mongol horde’s best bowmen brought down a flying duck with a single arrow through its neck. Another is said to have been able to hit a target 536 meters (1,759 ft) away. Carib archers of the 17th century could hit an English half crown coin at 76 meters (250 ft). Today, an average Olympic archer trains 40 hours a week. Mongol archers trained for 80 hours. They started at two years of age. It takes 10,000 hours of practice to reach elite level. By the time they turned 17, Mongol archers would have been practicing for 64,000 hours. Modern Olympic archers use high-tech, carbon-fiber recurve bows with sights and stabilizing weights. Mongol archers learned to shoot on horseback.

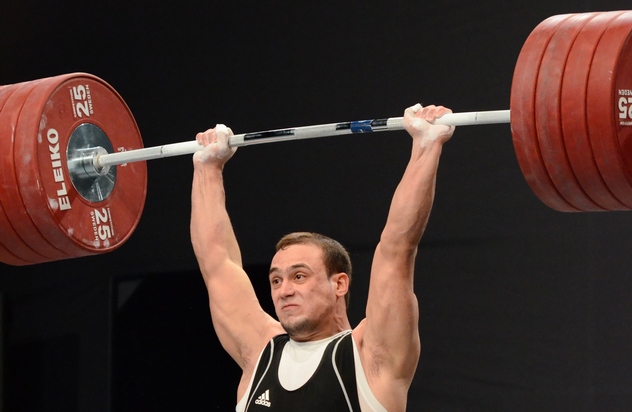

3Ilya Ilyin vs. Neanderthals

Kazakhstan isn’t just famous for inspiring British comedians to dress in dodgy green speedos and sing strange songs about potassium. Kazakh weightlifters are pretty good, too. Ilya Ilyin won gold in the 2014 World Championships. But no way would he have beaten a Neanderthal. With 20 percent more muscle mass than modern humans, male Neanderthals were 126–138 percent stronger than we are. Ilyin lifted 242 kilograms (534 lb) in the “clean and jerk.” His combined total was 432 kilograms (952 lb). With the same training, the strongest Neanderthal would have managed 309 kilograms (681 lb) and 554 kilograms (1,221 lb), respectively. In the women’s competition, China’s Zhou Lulu broke the 75-kilogram (165 lb) world record with a combined score of 328 kilograms (723 lb). The strongest female Neanderthal would have lifted 475 kilograms (1,047 lb), beating the current world record in the heaviest men’s class. Neanderthal women were 145 percent stronger than today’s ladies and had 10 percent more body mass than the average European man. They had shorter arms, so they could have lifted even more.

2Javier Castellano vs. Mongol Riders

Javier Castellano has earned more money than any other jockey in 2014—over $25 million. In 2013, the Venezuelan earned over $26 million. Genghis Khan’s Mongol warriors didn’t earn that much, but they could have beaten any of today’s jockeys in a straight race. For the nomadic people who lived on the Mongolian steppes back then, riding was like walking. A fully fledged warrior could ride 130 kilometers (81 mi) in a single day, traveling over mountains and deserts. Genghis Khan used the riders to send messages around his empire. When his grandson, Khublai Khan, lost favor with the nomads, the Mongols lost their empire.

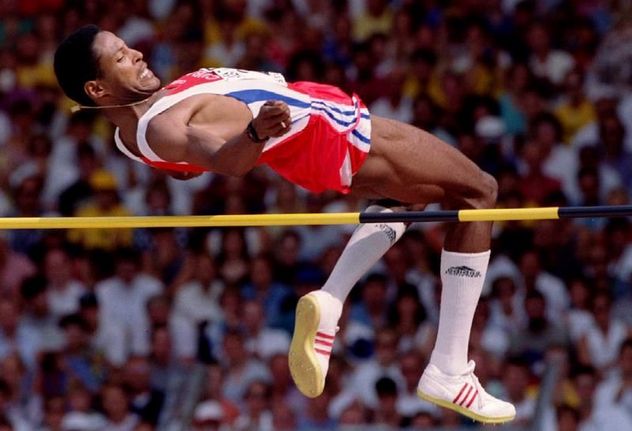

1Javier Sotomayor vs. Tutsi Men

High jumper Javier Sotomayor managed to clear a world record of 2.45 meters (8’0″) in 1993—pretty good for back then and too good for the world’s best since. But Sotomayor’s jump was nothing compared to the heights Rwandan Tutsi men were jumping daily during the 19th century. Olympic high jumpers battle for personal glory and team success. For the Tutsi, high jumping was more important than that. In their culture, you were only considered a real man if you could jump your own height. And many of these guys were tall enough to make NBA scouts drool. Frequently, Tutsis jumped over 2 meters (6’7″). One is said to have managed 2.52 meters (8’3″)—and that’s without any training or technique coaching. Teach him the Fosbury Flop—the midair wiggle that’s supposed to add extra height to a jump—and he’d have managed over 3 meters (9’10”). Crispin Andrews is a freelance writer from England. He writes about science, technology, popular culture history, sports, and the unexplained.