10 Chupacabras

Chances are, you’ve probably already heard of these gruesome vampires. Every night, they prowl through the arid landscape to fasten their fangs into livestock and drain their bodies dry. According to most, they possess long claws, terrifying red eyes, and a row of spikes running down their spines . . . or do they? There is no actual footage of their existence, but there are a handful of photos with images of the alleged creatures. Dead ones, at least. With bulging gray eyes and dry, hairless bodies, it’s easy to see how someone could mistake them for monsters. The legend of the chupacabra began circulating in Puerto Rico and Mexico after reports that dead sheep were found drained dry with puncture wounds. Then came sightings of the goatsuckers, which were described as being like dogs, rodents, or reptiles. However, according to science, the real chupacabras could be nothing more than wild dogs afflicted with severe mange. Mange is a disease that causes extreme hair loss. As mites burrow underneath the skin, inflammation thickens the skin, cuts off the blood supply to the hair follicles, and leaves the animal hairless and leathery. And since mange leaves animals greatly weakened, it would be easier for them to attack livestock than to hunt down faster prey, such as rabbits. In short, the legendary goatsuckers are nothing more than a pack of mite-infested coyotes.

9 Cattle Mutilation

In a widespread phenomenon stretching across America, cattle are turning up dead with their tongues and reproductive organs missing. Although more sensible people have blamed it on your everyday predators, there are some details in the corpses that don’t make sense. According to a veterinarian that had examined one of the bodies, there is just no way that a predator could be the culprit. The cuts were clean, almost surgical, with no blood or other bodily fluids surrounding the area. Furthermore, footprints around the corpses were completely missing, almost as if the cow had dropped from the sky. These mutilations are not new, either. They have been happening since 1972. Could extraterrestrial beings or mysterious cults be the culprit? There may be a more logical answer. Scavengers such as foxes can make off with a bit of the carcass’s flesh, thus answering the question of missing organs. Flies and their larvae will then feast on the softer body parts, such as the reproductive organs and tongues, making the wounds appear precise and surgical. Furthermore, a body lying in the sun will eventually burst open, leading to more surgical-looking tears. The blood that gathers at the bottom will be consumed by maggots. To top it all off, an Arkansas sheriff named Herb Marshall proved this by filming a cow decomposing in the sun, with the end result similar to the mutilations.

8 Zebra Riddles

You can often witness these black-and-white animals galloping across the African savanna with their unique coats dazzling in the sun. But just what do they need those stripes for? For the longest time, scientists have hypothesized that they are used as camouflage or perhaps to confuse predators. At the University of Calgary and UC Davis, scientists have carried out experiments to measure the distances at which predators and the zebras themselves can distinguish the stripes at different times of the day. Their discoveries were different than what many scientists had expected. For example, zebra stripes cannot possibly be used as an effective form of camouflage. Even if lions can’t see them, they would be able to smell them instead. The experiment showed that beyond 50 meters (165 ft) in daylight or 30 meters (100 ft) at twilight, when predators are active, the stripes are hard for them to distinguish. On moonless nights, all animals have difficulty seeing the stripes beyond 9 meters (30 ft), proving that they’re pretty much useless in blending in with trees or tall grass. Additionally, in treeless areas, lions could detect the outlines of zebras just as easily as they could see other grazing prey such as buffalo or deer. So what are the stripes really used for? Instead of warding off jaguars or lions, the stripes are actually effective in protecting against a different opponent: bloodsucking flies. The pattern of narrow stripes makes them unattractive to the insects due to waves of light bouncing off the zebra’s coat. In a different study, flies were shown to be more attracted to horses of a dark color rather than white because of the type of light waves bouncing off them. It turns out that the zebra’s array of zigzagging stripes boasts a startling way of combating their bloodsucking foes.

7 Dolphins Decoded

Who knows what these marine mammals are trying to say with their sly smiles and high-pitched clicks? Actually, for the first time, their whistles have been decoded by a computer. Dolphins are complex, social creatures that express their feelings through movements and sounds. Dr. Denise Herzing built a translator—called the Cetacean Hearing and Telemetry device—that was able to decode a whistle into a human word that we know. So what was this specific dolphin trying to say? The machine translated the whistle as Sargassum, a type of seaweed, although it is uncertain whether the dolphin actually saw the seaweed or was merely communicating with another family member. Herzing hopes that the machine will continue to help the team understand more of the dolphins’ exclusive language.

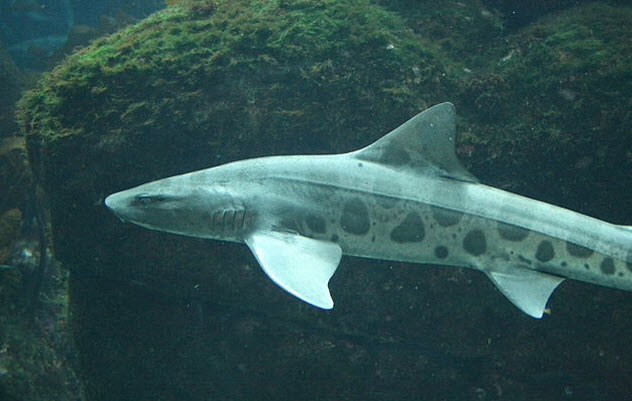

6 Shark Navigation

The ocean is vast and mysterious, spanning much of the world’s surface. So how do sharks manage to find their way through the unyielding seas? Scientists once believed that it might be through their sense of smell or magnetic fields, but no one knew for sure. To find the answer, researchers gathered some wild leopard sharks and led them about 10 kilometers (6 mi) away from their homes. Some of the sharks had their nostrils stuffed with cotton balls, and some did not. Then all the sharks were let loose to see how well they managed to find their way back. After heading the wrong way for 30 minutes, the unclogged sharks were eventually able to swim back to their shores. It was likely that they had sniffed out the increasingly higher doses of chemical molecules found near land. The sharks with the clogged nostrils, however, moved slowly and aimlessly. But how are we sure? How do we know that the slower sharks weren’t just distracted by the cotton balls shoved up their snouts? More studies found it unlikely that the sharks were following a scent that grew stronger near land. Instead, they may have used water temperature or light levels to guide them. While the mystery isn’t fully solved, this could be one step in finding the answer.

5 Deep-Sea Monster

The Tully monster is odd, to say the least. Fossils show that it had teeth at the end of a rodlike appendage on top of its head, eyes on either side of a rigid bar, and a stiffened notochord to support its body. Scientists have finally been able to identify the strange specimen after more than 50 years. Found in masses of hard rock, the 300-million-year-old fossils are only 0.3 meters (1.0 ft) long. With more advanced equipment, researchers were able to see the creature’s physical features by mapping out its chemistry. Although much of its lifestyle remains a mystery, we can conclude that it was a predator due to its many teeth. Still, we don’t have a clue when the Tully monster first appeared on the face of the Earth or when it became extinct.

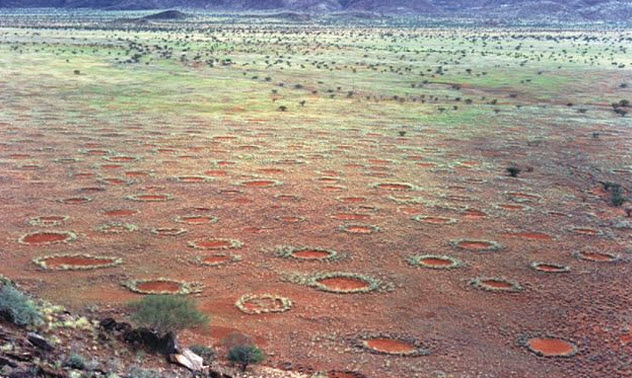

4 Desert Fairies

Fairy circles—round circles of bare sand surrounded by grass—are born in deserts and vanish in an eternal life cycle. The Himba bushmen living nearby believe them to be the footprints of gods, or perhaps they are indicators of a dragon’s underground burrow, the grass poisoned by its smoky breath. Maybe these impossibly perfect circles are the work of aliens or burrowing bugs. But the answer could be much simpler. The cause is neither dragons nor gods but quite possibly the plants themselves. With little water in a desert, it is impossible for grass to grow and carpet the entire area. Instead, the plants organize into clumps. These clumps can soak up water from the ground even months after the last rain. This also explains how vegetation can flourish around the circles even when the land surrounding them is dry and arid. Rainwater is greedily pulled from all directions by the desert’s thirsty plants. Certain spots become drier than others, and these areas become bare and impermeable. When it rains again, the water skims over the areas of dried clay toward the places where plants are growing. The plants survive and increase the size of their roots, pulling more of the rain away from their weaker neighbors. The smaller plants wither and die, resulting in a bare spot that becomes bigger over time. As individual plants compete randomly for water, a pattern is repeated all across a vast landscape. This process is known as the self-organizing theory because the plants formed the circles on their own without outside help.

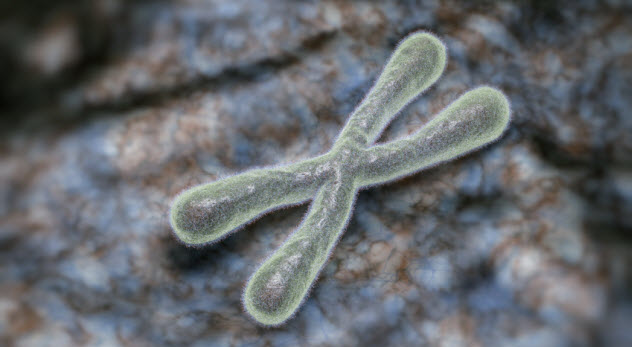

3 Path To Immortality

There are many animals that have lived well over a century. This includes Ming, a clam that died at age 507 and saw the fall of the Ming dynasty, as well as Charles Darwin’s pet tortoise, Harriet, that lived to age 176. Some tortoises have been known to live even longer. So what is the secret to their healthy, seemingly endless lives? The answer may lie in the enzyme telomerase, which keeps chromosomes from wearing out. But this leads to more questions than answers because we don’t even know how to keep ourselves alive for more than one century. It is uncertain how increasing telomerase activity can relate to aging and disease. Although there are correlations between the size of telomeres and longevity in shellfish, many types of cancer cells grow because they increase the length of their telomeres. Unfortunately, the long lives of these animals can be drastically cut short. Shark liver oil is a real product that is sold because sharks are believed to be immune to cancer(they’re not). However, there are no studies showing that it prevents cancer in humans. Additionally, tortoises can live for more than 200 years while staying cancer free. Still, it’s not possible to absorb their powers by consuming them.

2 Dodo Brains

The paintings of these long-dead birds have probably drawn an inaccurate picture in your mind. According to many, dodos are overweight and stubby, and they do not possess the brightest brains in the flock. What we know about them, however, could be wrong. A CT scan of a rare dodo skull suggests that they actually had the body type and size of our typical modern pigeon. Dodos probably also had the intelligence of a pigeon, which makes dodos a lot smarter than we once thought. Pigeons are capable of memorizing human faces and have mathematical abilities that are comparable to rhesus monkeys. The plump dodo that you see in paintings is probably the result of being confined to a cage and eating human food. Wild dodos are a lot thinner. According to the CT scan, the olfactory bulb of the brain suggests that dodos had a keener sense of smell than pigeons. It seems that these extinct birds deserve a lot more credit.

1 The 3,200-Kilometer (2,000 Mi) Journey

Every year, monarch butterflies soar toward the Rio Grande and travel a staggering distance to central Mexico. Even though the population has fallen due to the disappearance of the milkweed plant, their sole source of food, their journey continues generation after generation. How do they manage to travel that far without getting lost? Scientists have found a compass in their brains. It tells them two pieces of information: the time of day and the Sun’s position. The butterflies combine that information to find the right direction to go. Their complex eyes monitor the Sun, and then that information is combined with details picked up from their antennae to send signals to the brain. The butterflies use an internal clock built from the rhythmic expression of key genes. According to scientific models, the clock has a separation point to control the monarchs’ direction—whether they fly right or left to head south. “In experiments with monarchs at different times of the day, you do see occasions where their turns in course corrections are unusually long, slow, or meandering,” explained Dr. Eli Schlizerman of the University of Michigan. “These could be cases where they can’t do a shorter turn because it would require crossing the separation point. And when that happens, their compass points north-east instead of south-west. It’s a simple, robust system to explain how these butterflies—generation after generation—make this remarkable migration.”