10 Iron From Meteorites

In the northern Egyptian city of Gerzeh in 1911, archaeologists found a tomb that contained nine beads that appeared to be made of iron. The only problem is that they were dated from 2,000 years before Egypt had the capability to smelt iron. Since then, historians have puzzled over where the ancient Egyptians either found iron or learned to create it so early in their history. The Egyptian hieroglyphics for iron literally translate to “metal from heaven,” which gives a pretty good clue as to its origins. Because of the rarity of the metal, it was mainly associated with wealth and power. It was mainly crafted into jewelry and trinkets for royalty rather than weapons as it was later used. In the 1980s, chemical analysis showed levels of nickel, a metal associated with meteorites, but levels were too low to confirm. Recently, however, tests have conclusively shown that the iron did indeed come from fallen meteorites which would explain why the metal appeared thousands of years before the Egyptians learned to smelt it. Interestingly, this would also explain the mystery of King Tut’s dagger. Along with a gold blade, a mysterious dagger apparently made of iron was found at Tutankhamen’s side. Since King Tut died before iron was smelted, it was theorized that his dagger came from fallen meteorites. After testing, this theory was finally proven true.

9 Religious Tattoos

Today, many people will get tattoos for a variety of reasons: to remember a loved one, to express uniqueness, or to show off their interests. But a mummy found in the village of Deir el-Medina shows what the ancient Egyptians may have used them for. Along with other mummies with visible tattoos, the Deir el-Medina mummy sheds light on a possible ancient religious practice. The Deir el-Medina mummy is a headless, limbless torso that belonged to a woman from between 1300 and 1070 BC who lived in an artisanal village near the Valley of the Kings. Using infrared lights, 30 identifiable tattoos were found on her. What’s unique about her is that the tattoos appear to have been put on her during her lifetime rather than after death for a religious ritual. She also has the first symbols that have significance rather than abstract designs. These symbolic designs range from the so-called Wadjet eyes on her neck, shoulders, and back (which represent divine watching from every angle) to cows related to the powerful god Hathor. Other symbols were found on her neck and what remained of her arms. Most likely, they were also related to Hathor and were supposed to be a sort of boost for singing and playing music. When the discovery of the tops was made, many Egyptologists were stunned because no tattoos of the sort had been found before. Three similar mummies were found, and their markings were most likely for women who wanted to express their religious piety. To get the tattoos would have been test enough because the method used was probably excruciatingly painful.

8 Depiction Of Demons

As far back as 4,000 years ago, Egyptians feared demons and what they would do to these ancient people. Of course, the ancient Egyptians were very religious people and their beliefs were passed down so effectively that we have a good grasp on their deities and practices today. However, when it comes to demons in Egyptian’s minds from the distant past, we were mostly in the dark as to what they imagined them to be—until now. Two demons found on a coffin from the Middle Kingdom (around 4,500 years ago and the oldest depictions thus far) show exactly what the Egyptians believed were out there and what they would do to you. One named In-tep is a doglike baboon and the other named Chery-benut is an unspecified creature with a human head. They are depicted as two guards of an entrance but what they actually did is unknown. According to archaeologists, In-tep may have punished intruders who entered sacred spaces by gruesomely decapitating them. Ikenty, a third demon also found on a Middle Kingdom coffin, was depicted as a large bird with a feline head. But an even older depiction found on a Cairo scroll describes it as a demon that could very quickly identify victims and hold them in its inescapable grasp. Although demons were commonly depicted in Egyptian findings from the New Kingdom (1,000 years after the Middle Kingdom), it shows that belief in evil spirits by the ancient Egyptians occurred far earlier than previously thought by experts.

7 Ancient Heart Disease

Atherosclerosis, the hardening of the coronary arteries, is a common disease in modern populations. Sedentary lifestyles, diets rich in fatty foods, and more contribute to this disease. Seeing as most of its causes were almost nonexistent in the past, it would stand to reason that atherosclerosis would not be common in ancient populations. According to Egyptologists, it was actually a common affliction. A study of 52 mummies at the National Museum of Antiquities in Cairo showed that 20 of them exhibited signs of calcification, which means that they most likely suffered from atherosclerosis during their lifetimes. As one would expect, those who had the disease had lived the longest. Their ages averaged around 45, and they lived during the 16th century BC. One of the mummies was royalty: Princess Ahmose-Meryet-Amon who lived in Thebes and died in her forties. She is the oldest recognized person to have coronary heart disease. A scan of her arteries showed that enough were clogged to warrant bypass surgery if she were alive today. However, her diet and that of other ancient Egyptians was the exact opposite of most heart disease victims today: fruit, vegetables, wheat, beer, and lean domesticated meats. So why was heart disease common? Parasitic infections were frequent in ancient Egypt, and the inflammation would have caused some to become more susceptible to heart disease. Salt for preservation may have been another factor. Finally, in the case of the princess, a diet of luxuries like meat, cheese, and butter could have caused her heart disease like most people today.

6 Egyptian Hair Work

When a woman’s hair starts to thin out today, there are multiple options to fix it. Apparently, women in the past had the same problem because the body of a woman found in the ruined Egyptian city of Amarna had 70 hair extensions similar to those we have today. The extensions were so well done that they were preserved to this day even though the rest of her body decomposed. The woman’s body wasn’t mummified but remained in fairly good condition considering that she most likely died 3,300 years ago. Although it is believed that the hair extensions were placed on her for burial, evidence suggests that people at the time also used the same extensions in everyday life. In the cemetery in which the woman was buried, other bodies with interesting hair work were found. One woman with graying hair was actually found to have dyed her hair using the henna plant. She had dyed her hair for the same reason that we do today. She wanted to cover up her gray spots. All together, there were 28 skeletons with hair still attached, all displaying different hairstyles. The most common was tight braids around the ears. To keep the hair in place after death, some kind of fat was used. It seems to have worked well because the hair is still preserved to this day.

5 The Mummified Fetus

About 100 years ago, a 45-centimeter (17 in) coffin was unearthed in Giza. It was transported to Cambridge University where it was put away and left unchecked for the next century. At the time, all that was made of the bundle inside was that it was just some organs put into the tiny coffin for some unknown reason. However, after researchers found the coffin, they examined the bundle and came to a startling new conclusion. Watch this video on YouTube A CT scan showed that it was actually a fetus and that it had been carefully preserved and buried in its own specially built coffin that contained intricate designs and decorations. Aged just 16–18 weeks, it is the youngest mummy ever found as of mid-2016 and the only academically verified, mummified fetus from this gestational period discovered thus far. It shows just what lengths the ancient Egyptians would go to honor the dead and especially their young during the first weeks of life. It was most likely a miscarriage, a significant occurrence in ancient Egypt considering the care given to other mummified fetuses that have been discovered. Two mummies found in King Tut’s tomb were buried in individual coffins of their own. The baby itself was mummified using the same methods as full-size mummies. Its arms were crossed over each other as other mummies are and had no deformations of any kinds. In the words of the museum where the mummy now resides: The efforts taken for the mummy, “coupled with the intricacy of the tiny coffin and its decoration, are clear indications of the importance and time given to this burial in Egyptian society.”

4 Cancer In Egyptians

Like heart disease, cancer has been described by some as a strictly modern disease, and it is true that cancer is mostly absent from historical records. However, that doesn’t mean that it didn’t occur in the ancient world. Discoveries in the past few years have shown that cancer did indeed show up in ancient Egypt, and we still have the proof. Two mummies, male and female, both show signs that they suffered from the disease. In 2015, a Spanish university found a mummy that showed evidence of deterioration from breast cancer. Authorities now say that the mummy is the oldest victim of breast cancer in history. The 4,200-year-old mummy lived during the sixth pharaonic dynasty, and her bones showed extreme deterioration that is consistent with cancer. According to the Egyptian antiquities minister: “The study of her remains shows the typical destructive damage provoked by the extension of a breast cancer as a metastasis.” She lived in Elephantine, the southernmost town in ancient Egypt at the time. A 3,000-year-old mummy found in Sudan near Elephantine also showed breast cancer, which suggests that it was in the Nile Valley at the time. In 2011, a 2,250-year-old male mummy known as M1 was found with the oldest case of prostate cancer in ancient Egypt. Researchers have suggested that the reason cancer wasn’t often found in mummies in the past was simply a matter of available technology. We now have scanners that can detect tumors as small as 1.0 centimeter (0.4 in) that are commonly found on the spine after prostate cancer spreads. Possible causes for cancer in ancient times range from the bitumen used for building boats to smoke from wood-burning chimneys.

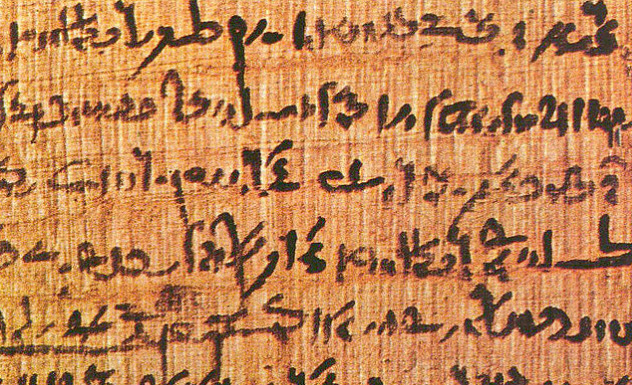

3 The Oldest Papyri In The World

In 2011, archaeologist Pierre Tallet made a remarkable discovery in a remote area of Egypt far away from any civilization. Thirty honeycombed caves in a limestone cliff turned out to have been a sort of boat storage depot in ancient Egypt. But even more stunning was a discovery he made a few years later in 2013—a series of papyri written in both hieroglyphics and hieratic (an informal, everyday sort of writing by ancient Egyptians) that are the oldest papyri ever discovered. Tallet had used instructions given by an Englishman in the 19th century and French pilots in the 1950s to find the caves. The papyri are so old that the author actually wrote about the construction of the Great Pyramids of Giza. They also show that Egypt at the time had a bustling shipping economy that stretched across the entire empire. During the construction of the pyramids, all of Egypt was interconnected to enable the massive project. The journal of an official named Merer was among the papyri. Apparently, Merer supervised a group of 200 men responsible for crisscrossing ancient Egypt and gathering supplies like food for workers or the massive amounts of copper needed to sand the limestone for the Great Pyramid’s exterior. They went to Tura, a city on the Nile River famous for its limestone quarries, and actually dealt with Ankh-haf, the half brother of Khufu. The journals of Merer come from the last known years of Khufu’s reign and provide an account of the finishing touches of the first and largest of the pyramids in Giza. It is the only account we have of the building of the Great Pyramids. According to Zahi Hawass, former chief inspector of the pyramid site, this makes the journals “the greatest discovery in Egypt in the 21st century.”

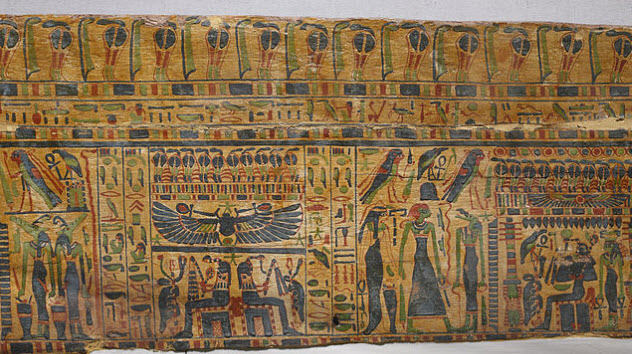

2 Ancient Egyptian Brain Drain

In 525 BC, Persian King Cambyses marched into the Egyptian capital of Memphis, which began a century-long rule over Egypt by Persia. During this time, most of the great Egyptian minds and artists were taken to Persia to serve the empire there. Meanwhile, back in Egypt, there was a sort of brain drain in which they were left with artists who were not talented enough for the Persians. This is evident from a coffin discovered in 2014. Although whoever was buried in it is now gone, tests show that the coffin dates from around the time of the Persian occupation. Even more interesting are the designs on the coffin, which can be described as incredibly mediocre. They are so poorly done that some experts initially believed that the coffin was a fake. However, the coffin was authenticated when it was proven to have the ancient Egyptian pigment known as Egyptian blue. The shoddy work was, in fact, the result of the best Egyptian artisans being taken to work in Persia. There are a variety of bizarre images on the coffin, including poorly drawn falcons (representative of the god Horus) that appear fishlike, four jars with the heads of the four sons of Horus that are described as “goofy,” the only known image of a bed with the head of the deity Ba, and the goddess Hathor depicted with a snake-shaped crown that is also an oddity in ancient Egypt. Other clumsy mistakes made by the artist have made experts wonder just how bad the art world in Egypt deteriorated during this period. Ancient texts by Diodoros Siculus, who died in 30 BC, record that all precious metals and artists were removed by Cambyses during the Persian occupation and that King Darius I of Persia reportedly bragged about the Egyptian artisans that he had gathered to build his palace in Susa.

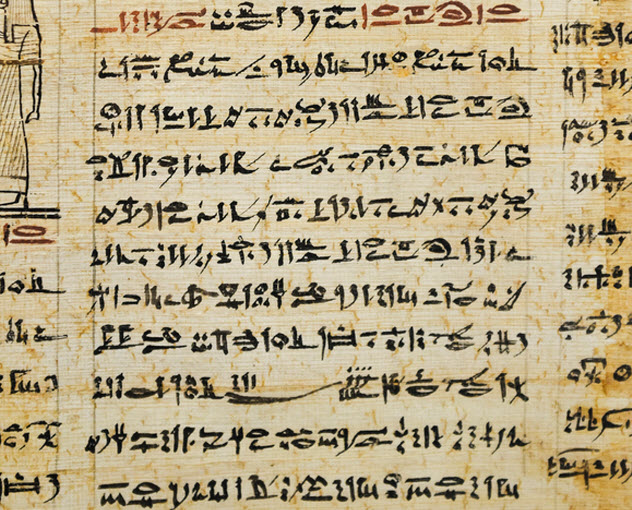

1 Egyptian Sex Spells

In 2016, two papyrus scrolls from the third century AD were deciphered from the Greek in which they were written. Over 1,700 years old, the scrolls had been found a century ago with several scrolls that were held at the University of Oxford in England until recently when they were translated. The subject of the two scrolls was sex spells to make whomever the caster wanted love them in return. The spells were not exclusive since you could essentially put whatever name you wanted in them to get the desired effects. Apparently, one of the spells invokes the gods to “burn the heart” of a woman until she loved the caster. Another one for females was supposed to allow the caster to “subject” the male to whatever she wanted to force him to do. The author of the spells is unknown, but they were apparently Gnostic as several Gnostic gods are actually mentioned in the spells. The spells give an interesting insight into the superstitions and beliefs of Egyptians so many centuries ago. With the men’s spell, the caster was supposed to burn various ingredients in a bathhouse (the list of ingredients didn’t survive the degradation of the scroll) and then write a set of words on the bathhouse walls. The spell then lists magic words and the names of several gods. Finally, the scroll says: “Holy names, inflame in this way and burn the heart of her” and so on until the subject falls in love with the caster. The spell for females says to inscribe a certain text in a copper plate and then attach it to one of the subject’s possessions. The result was to make him do whatever the caster wanted. Interestingly, the back of the scrolls contained recipes for various potions, including a mixture of honey and bird droppings that was supposed to “promote pleasure.” Gordon Gora is a struggling author who is desperately trying to make it. He is working on several projects, but until he finishes one, he will write for Listverse for his bread and butter. You can write him at [email protected].