Whatever the causes, the consequences of filming bad horror movies plagued by even worse production problems can provide unintended entertainment, albeit probably not for those who were directly involved in the filmmaking. A few such films even become cult classics. Let’s go backstage to see how directors, actors, and film crews have dealt with the production problems that plagued their low-budget films.

10 Beast from Haunted Cave

The title of Beast from Haunted Cave announces the 1959 movie’s premise. Marty Jones and Natalie, a barmaid, set off an explosion in a mine to divert attention from the gang’s robbery of a Deadwood, South Dakota, bank vault full of gold. In the process, they encounter a monster. Although Natalie is killed, Marty escapes, but not for long, as additional encounters between the gang and the monster occur. According to Bill Warren’s Keep Watching the Skies!: American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, a wingless hangingfly inspired the generally panned film’s monster. Chris Robinson, the monster’s creator, wore the clumsy suit constructed of aluminum strips, plywood, and chicken wire wrapped in muslin. The “lightweight structure,” Warren reports, increased Robinson’s own apparent height to seven feet and was equipped with “spindly legs and tentacles.” Inside the suit, Robinson moved in a “jerky, floppy manner” suggesting that the monster was no threat to any of the more agile human characters it attempted to pursue.

9 What Waits Below

An accident put the brakes on Don Sharp’s 1984 movie What Waits Below, in which a team of military personnel and cave experts respond to the abrupt disappearance of a radio transmission from a deep cave system in Central America. In an issue of Imagi Movies, actress Lisa Blount, who played scientist Leslie Peterson, recounted the incident, which occurred while her character, who had been captured, was “tied up . . . inside the cavern.” At the time the scene was being shot, she said, “All the extras . . . were out in front” of her when she saw them “just start silently falling over.” As it turned out, she explained, the actors were “fainting, as this wave of carbon monoxide came at them.” They needed to get out of the cavern as quickly as possible, Blount recalled, but their only means of transportation were the “slow” golf carts they had on hand. “The youngest” among them were dispatched before the others, she said, as the carbon monoxide’s presence in the close confines of the cavern was exacerbated by a backed-up generator’s “shooting fumes back into the cave.” The accident shut down production for “a few days,” Blount said, but she escaped harm, and nobody else suffered long-term injuries.

8 The House on Sorority Row

Mark Rosman, the director of The House on Sorority Row (1982), in which a group of members prank their house mother, found an opportunity too good to pass up: he was able to rent a Pikesville, Maryland, house that had gone into foreclosure. However, when the film crew arrived to start shooting, they encountered an unexpected problem: two squatters had taken up residence in the supposedly empty house. Fortunately, this situation wasn’t a setback. The filmmakers had a solution that proved satisfactory to all: the squatters became the production crew’s video assistants.

7 Terror Train

During the filming of Roger Spottiswoode’s Terror Train (1980), which features murders during a costume party attended by fraternity and sorority members that is in full swing aboard a train, the fear of one of the crew caused a production problem. According to David Grove, the author of “Jamie Lee Curtis: The Making of a Scream Queen—Terror Train,” a stuntman who was portraying a dead character afloat in the icy waters of a ravine was frightened by the water’s frigid temperature and “kept trying to swim instead of playing dead.” Art director Gary Comtois traded places with the stuntman, and the filming of the scene was successfully completed. The narrow confines and the poor lighting aboard the train in which most of the film’s action was shot also presented a production problem. In an interview with The Terror Trap, Spottiswoode explained how John Alcott, his cinematographer, overcame this technical difficulty. First, Alcott hired electricians to rewire the whole train. The electrical wires were attached to “long wooden boards,” Spottiswoode explained, to which “dimmers” could be fixed. To facilitate the change of the wattage of the lights, “boxes and boxes of bulbs,” ranging from 20 to 100 watts, were purchased, Spottiswoode recalled, which enabled the crew to easily “change the lights” and either dim or illuminate the set “very, very fast.” The changes in the intensity of the light accentuated the terror aboard the train as the murderer picked off one partygoer after another. The lighting effects were improved by other technique as well, the director said: To prevent “reflected light [from] bouncing off walls,” the walls were “painted dark,” and Alcott would position himself behind the camera and, using a penlight, “pick . . . people’s eyes out” of the darkness, increasing the eerie quality of the dimly lit or, at times, completely dark interior of the train.

6 Attack of the Crab Monsters

A movie that is largely shot underwater is apt to involve a few production problems, especially when the picture is filmed on a shoestring budget. Roger Corman’s 1957 film Attack of the Crab Monsters certainly did. The movie is based on a simple, somewhat silly premise: scientists who are searching for an expedition that never returned from an island on which they were conducting research also become cut off from the rest of the world. To make matters worse, the isolated scientists find themselves among intelligent crabs intent on the scientists’ gruesome destruction. One of the movie’s production problems resulted from mixed signals, as the movie’s screenwriter, Charles B. Griffith, who also directed the filming of the undersea scenes, explained in an interview with Aaron W. Graham. During a filming session at Marineland, Griffith would “be down at the bottom of the tank . . . trying to get actors to do something” while [director of photography] Floyd Crosby was hammering on the glass window trying to get them to do something else.” Another problem concerning the film might have been the script itself. Corman and Griffith disagree to some extent on this matter. The director wanted a fast-paced, action-packed movie, each scene of which either ended in a cliffhanger or foreshadowed something horrific to come. As Griffith put it, Corman wanted “suspense or action in every scene. Period.” Although Griffith complied, he wasn’t sure that this was the best way to go about plotting the picture. “I put suspense or action in every scene and, when I went to go see it, the audience fell asleep!” he reported. On the other hand, for Corman, the non-stop action, horror, and suspense approach resulted in “the most successful of all the early low budget horror movies” because it focused more on spectacle and special effects than on character development and “subplots.” His insistence on non-stop action and suspense, he said, worked because the audience “always had the feeling when watching the movie that something, anything was about to happen.” Critics’ reviews, as represented by the Rotten Tomatoes website, are mixed, but are presently more positive than negative, with five of the seven critics who have ventured an opinion on the film awarding it a ripe, red tomato for its “Fresh status” and two giving it “a green splat” to represent the movie’s “Rotten status.” So far, it seems that the critics are more in agreement with Corman than they are with Griffith on the merits of the picture.

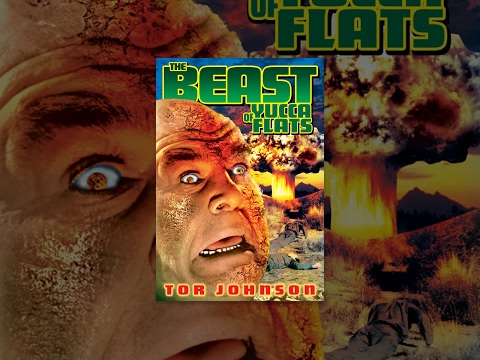

5 The Beast of Yucca Flats

A poster promoting Coleman Francis’s The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961) suggests the paper-thin plot: “Commies made him an atomic mutant.” The “him” to which the poster’s tagline refers is Soviet scientist Joseph Jaworsky, a defector who is transformed into a monster when, fleeing KGB agents, he enters a U. S. atomic weapons test area while a nuclear test is being conducted. The movie is widely considered to be not so much horrific as just plain horrible. According to Producer Anthony Cardoza, “a [retired] 29-year-old welder,” the cast consisted of anyone whom he and his associates could cobble together, including an actor’s friend, an ex-wife, the wife of another of the movie’s several producers, and four of the producers themselves. The only actual actor in the film was the star, former wrestler Tor Johnson. The special effects may have been effective, but they were also cheap: “wrinkled up” toilet tissue, Cardoza said, was “pasted onto Tor,” presumably along with makeup, to create the appearance of scars from the “atomic blast,” which was supplied by “stock footage.” Cardoza said that interior sets were kept to a minimum as well; there were two, a bedroom and an apartment. Cardoza played the husband of actress Marcia Knight when the actor who was supposed to portray her spouse “never showed up.” The inclusion of gratuitous nudity suggests how little consideration was given to the movie’s plot, to say nothing of its artistic integrity. The only reason that the apartment appears in the film is to showcase the nude actress who paces about inside it during the movie’s pre-credits sequence before the Beast kills her. When asked the reason that this footage was included, Cardoza, who was very forthcoming during his interview with Tom Weaver, admitted, “Coley [director Coleman Francis] liked nudity.”

4 Birdemic: Shock and Terror

It’s difficult to improve on genius, but the challenge didn’t stop director James Nguyen from trying: his 2010 movie Birdemic was inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. (Tippi Hedren even makes a cameo appearance!) In fact, Carl Daft, the CEO and co-founder of Severin Films, billed the film as “the greatest avian-based romantic thriller since THE BIRDS.” Nguyen used income from his “day job” to finance the movie, which he also wrote and produced, and, according to interviewer Brad Miska, “also tackles topical issues of global warming, avian flu, world peace, organic living, sexual promiscuity and lavatory access.” The 93-minute movie offers something for everyone, apparently. It’s plot, Miska says, “is a horror/action/special-effects-driven love story about a young couple trapped in a small Northern California town under siege by homicidal birds.” To promote Birdemic, Miska recounts, “Nguyen spent eight days driving up and down the [Sundance] festival’s nearby streets in a van covered with fake birds, frozen blood and BIRDEMIC posters, while loudspeakers blared the sounds of eagle attacks and human screams. The tactic caught the attention of festival organizers, filmgoers and local police.” Fortunately for the Silicon Valley mid-level software salesman-turned-screenwriter-director-and-producer, the tactic also intrigued Severin Films executives, who, impressed by what they saw when they watched the movie, contracted for worldwide rights to the film for twenty years. Critics haven’t been as enthralled by Birdemic. Bloody Disgusting’s David Harley said the film “easily makes it onto my Top 10 Best Worst Films of All Time list,” classifying it as a “beautiful disaster . . . so mind-numbingly inept and awful in every conceivable way that it’s mesmerizing.” Apparently, audiences enjoy the film that Miska called “one of the best bad movies ever made”: a sequel was released in 2013, and a third recently began production.

3 Plan 9 from Outer Space

The resourcefulness of “B” horror movie production crews is also demonstrated by Ed Wood’s 1957 cult classic Plan 9 from Outer Space. With the words “Outer Space” in its title, a movie is likely to include footage of alien spacecraft. Wood’s picture was no exception to this expectation. Automobile hubcaps stood in for the alien spaceships, some claimed. However, such was not the case. Instead, Wood used “plastic model kits of flying saucers,” the April 2020 issue of Retro Fan points out.

2 Invaders from Mars

Invaders from Mars, director William Cameron Menzies’s 1953 creature feature, employed several “cheap props, including a car headlight for a space gun” and the set decorator’s own “glass table from home.” One of the most bizarre props in the movie, though, are the ordinary, “everyday white condoms” used to create what passes for “cave wall bubbles.” As John “J.J.” Johnson points out, in Cheap Tricks and Class Acts: Special Effects, Makeup and Stunts from the Films of the Fantastic Fifties, the filmmakers of that decade were nothing if not “resourceful when it came to cutting costs.”

1 The Visit

Despite some winners, N. Night Shyamalan has directed so many losers that it is difficult to say which one is the worst. Contenders for this position, however, must include Lady in Water (2006), The Happening (2008), The Last Airbender (2010), After Earth (2013), and Glass (2019). Indeed, his flops have caused him to lose so much status as a director who makes bankable films that, to finance The Visit (2015), he had to borrow $5 million on his “125-acre country estate west of Philadelphia,” points out Rolling Stone writer Brian Hiatt. His losing streak has made Shyamalan seriously doubt his own talent. “The world of my industry decides I have no worth,” he said, describing how he began to question his abilities. “I am a cautionary tale. A person who got lucky for a time but revealed himself to be a sham. . . . I do not believe in myself.” The director hoped to turn things around, artistically and financially, with The Visit, a found-footage film in which teenager Becca and her younger brother Tyler, visiting grandparents they have never met before, are frightened by their elders’ bizarre behavior. The O. Henry of horror and fantasy films, Shyamalan has been criticized for the plot twists typical of his films’ endings, many of which critics contend are contrived. As his movies’ box office receipts took a nosedive, the director refrained from including such surprises—until The Visit, for which, Hiatt reveals, Shyamalan “brought back his signature this-wasn’t-the-movie-you-thought-it-was twist.” Possibly as a result of this reversal, no one would touch the movie. When “he flew to L. A. [to show] a rough cut [of the film,] every Hollywood studio . . . passed” on it. Shyamalan feared he would lose the $5 million he had borrowed against his house and that his latest filmmaking fiasco might be his last. However, Hiatt discloses, the director filmed a “new cut” of the film, showed it to Universal, and horror maven Jason Blum signed on as a producer. The film ended up making $98 million.” Perhaps Shyamalan’s belief in a “fundamentally benevolent” universe is true, after all, despite even the missteps he made with Lady in Water, The Happening, The Last Airbender, After Earth, and Glass.