10Ludwig Leichhardt

Western Australia’s Great Sandy Desert is believed to be the last resting place of one of Australia’s greatest explorers: Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt. Lauded as the “Prince of Explorers,” Leichhardt was a Prussian natural historian who voyaged Down Under in 1842, planning to find work as a scientist. When nobody would hire him, he struck out on his own, single-handedly documenting everything from geology to Aboriginal customs to the best designs for sheep sheds. In 1844, the governor decided against funding an expedition across eastern Australia. Always a self-starter, Leichhardt decided to organize his own, trekking overland on a perilous 5,000-kilometer (3,000 mi) journey from Queensland to Port Essington in the Northern Territory. Despite harsh conditions, deadly Aboriginal attacks, and an incident where his hat was set alight while he slept next to the fire, Leichhardt triumphantly reached his destination in December 1845. Since everyone had already given his party up for dead, they were given an ecstatic reception and Leichhardt became a national hero. In 1846, Leichhardt announced his most ambitious (and dangerous) journey yet: a 4,500-kilometer (2,800 mi) east-to-west expedition from the Darling Downs in Queensland that would reach the west coast before turning south for the safety of the Swan River and Perth. An early attempt was forced to turn back almost immediately, but Leichhardt set out again in 1848, accompanied by five Europeans and two Aboriginal guides. Despite many search attempts, the expedition was never heard from again. Part of a gun suspected to be Leichhardt’s was found in the desert in 1900, but otherwise his fate remains a mystery. One theory even suggests that a sudden flash flood overtook the party, drowning them and burying the evidence beneath a thick layer of sediment.

9Gaspar And Miguel Corte-Real

In 1503, the Portuguese courtier Vasco Corte-Real equipped two ships for an expedition to what is now Northeastern Canada. His goal was to search for his younger brother Miguel, who had vanished off the coast of Newfoundland while searching for his even younger brother Gaspar, who had also vanished off the coast of Newfoundland. Sensing the pattern, the Portuguese king eventually stepped in and banned Vasco from going anywhere near the coast of Newfoundland. To this day, the disappearance of Gaspar and Miguel remains one of the most intriguing mysteries in Portuguese naval history. The three brothers were the only sons of Joao Vaz Corte-Real, a notoriously cruel landlord from the Azores, and his kidnapped Spanish wife. Joao Vaz himself made a poorly recorded voyage to the north in the 1470s, leading some to theorize that he reached the Americas before Columbus. (It’s more likely that he just cruised around Greenland for a while.) His sons seem to have inherited his interest in the region, prompting Gaspar to voyage to Greenland and Newfoundland in 1500. In 1501, Gaspar set sail with three ships to explore the region further. The expedition reached Newfoundland without incident, but then a storm separated the ships. Two returned safely to Portugal, but Gaspar’s ship was never seen again. Desperate to find Gaspar, Miguel Corte-Real quickly outfitted three caravels of his own and sailed in May 1502. After exploring Labrador and Newfoundland, the three captains agreed to split up in order to search a wider area. They were supposed to rendezvous a month later, but Miguel and his ship never showed up. Historians now speculate that one or both Corte-Real brothers may have sailed north along the coast of Labrador and into Hudson’s Bay, where they would have been trapped by ice as the weather grew colder. Whatever their fate, the Corte-Reals’ disappearance brought Portuguese Arctic exploration to an abrupt end.

8Abu Bakr

In 1324, the famously wealthy Malian ruler Mansa Musa (pictured above) made his celebrated pilgrimage to Mecca. In Cairo, he was a guest in the home of the scholar and official Abu’l Hasan Ali, who recorded the unusual fate of the previous Mansa of Mali, Abu Bakr II. According to Musa, Abu Bakr “did not believe that it was impossible to discover the furthest limit of the Western Ocean and wished vehemently to do so.” Even after ascending to the Malian throne, his heart continued to ache for the endless possibilities of the oceans. After a preliminary expedition into the Atlantic failed to return, Abu Bakr decided to lead the follow-up himself. As a result, he abdicated his throne in 1311 and outfitted 2,000 vessels of unclear design, filled with fresh water and other provisions. In Musa’s words, Abu Bakr then “left me to deputize for him and embarked on the Western Ocean with his men. That was the last we saw of him and all those who were with him.” The story has fired the imaginations of generations of historians, who have speculated that Abu Bakr might have successfully reached the Americas. In fact, given the position of Mali and the preparations described by Musa, it’s actually very likely that at least a few members of the expedition would have made it through. However, there are two major caveats. Firstly, no unambiguous evidence of Malian presence in the Americas has yet been discovered. And secondly, Mansa Musa himself was clearly behind Abu Bakr in the line of succession. As a result, some historians think that the rightful heir simply sailing off into the ocean sounds a little too convenient. They suspect that Musa staged a coup and then constructed the story of his predecessor’s voyage as a convenient way of justifying his own rule.

7Park Young-Seok

The mighty Himalayan peak known as Annapurna I is one of the deadliest climbs in the world, with an astonishing fatality-to-summit ratio of 38 percent. But that didn’t faze legendary South Korean climber Park Young-seok. The intrepid mountaineer had set records across the globe, including becoming the first person to achieve the “Adventurer’s Grand Slam” by climbing the 14 highest Himalayas, the highest mountain on each continent, and reaching the North and South poles. Along the way, he developed a reputation as the bad boy of the exploring world. (It was rumored that he stole the South Pole marker.) But Park was a deadly serious climber at heart, once setting a record by scaling six of the tallest Himalayas in one year. While trying to establish a new route on the south face of Everest, two of his closest friends were killed in a fall. Park went on a drinking binge for six months and then reappeared, vowing “to conquer the peak at any cost.” He succeeded in 2009, pioneering the new line on the mountain’s south face. Throughout his career, Park famously refused to quit smoking, predicting that he would be killed long before cancer could catch up with him. In 2011, his prediction came true as he and two companions vanished while trying a new route up Annapurna I. He was last heard from on October 18, when he radioed his intention to return to base camp following a gale and rockslide. A search party discovered a rope buried in the snow, but no trace of Park or his team members could be found.

6Vadino And Ugolino Vivaldi

Imagine if some bold explorer had pioneered the sea route from Europe to India centuries before Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama. Well, that’s exactly what the brothers Vadino and Ugolino Vivaldi attempted to do in 1291. The Vivaldi were Italian merchants close to the wealthy Doria family of Genoa, who probably financed the expedition. (A man named Tedisio Doria accompanied the brothers). Details are scarce, but we know that the brothers set off in two galleys and passed through the Strait of Gibraltar in May, intending to journey across “the Ocean Sea to parts of India and to bring back useful merchandise from there.” Interestingly, the Genoese annals don’t specify the route they intended to take, leading some historians to suggest they were trying to reach India across the Atlantic, just as Columbus would do 200 years later. However, it remains much more likely that they were planning to hug the coast of Africa, which would have been at least somewhat safer in the primitive galleys of the 13th century. According to the Genoese chronicler Jacopo Doria, the brothers reached a place known as Gozora before disappearing into the unknown, never to be heard from again. Historians are somewhat divided on the matter, but the most likely explanation is that Gozora refers to the African coast near the Canary Islands, in what is now southern Morocco. The Genoese admiral Benedetto Zuccaria was cruising the Moroccan coastline with a Spanish fleet at the time, so it’s not surprising that Jacopo Doria would have heard of the brothers passing through. But afterward the Vivaldi passed out of the sphere of European knowledge, and nobody knows where they went or how far they traveled before their voyage reached its end.

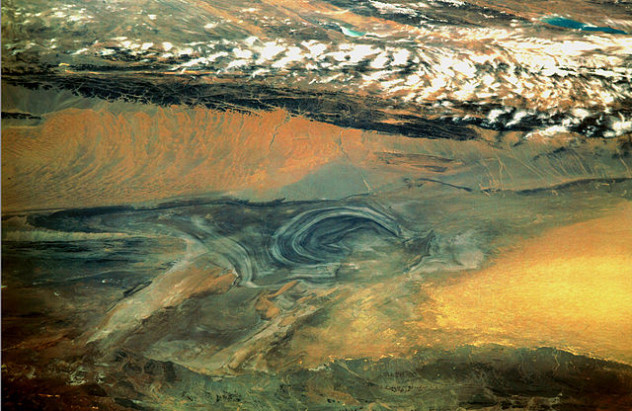

5Peng Jiamu

The fearsome reputation of China’s forbidding Lop Nur desert didn’t deter the brilliant biochemist Peng Jiamu—if anything, it heightened his curiosity. As Jiamu himself wrote in his application to explore the area, “I have a strong wish to explore the frontiers. I have the courage to pave a way in the wilderness.” Ironically, Lop Nur spent most of its history as a huge area of marshy lake in the Xinjiang region of northwestern China. However, the marsh dried up after a dam was built in the area, forming a shifting desert of sand and salt. Peng Jiamu arrived in the area in 1964, having abandoned his plans to study abroad in order to take part in an expedition measuring potassium deposits in the desert. Over the next few years, he braved terrifying conditions in an area where hundreds of people have been killed by extreme weather and collapsing dunes. In the process, he discovered a wealth of valuable information, including several new species of animal. The Cultural Revolution put exploration on hold, but Peng returned to the desert in the summer of 1980, leading a team of archaeologists, biologists, geologists, and chemists. Five days into the expedition, the team was short on water and growing nervous, but in a speech his comrades never forgot, Peng persuaded them to go on, declaring that “science is to walk a road not travelled by other people!” A few days later, Peng left the camp to search for water and never came back. His disappearance shocked the nation and a huge search effort was launched, but no trace of the scientist could be found. Every so often, the discovery of human remains in the Lop Nur will cause excitement in China, where Peng remains a hero, but so far none have been shown to belong to him.

4Francisco De Hoces

Relatively little is known for sure about Francisco de Hoces, but we can say that he was a Spanish sailor who joined Jofre de Loaisa’s 1525 expedition, which aimed to follow Magellan’s route around the southern tip of South America and across the Pacific. For most of history, the expedition was best known for the participation of Juan Sebastian Elcano, who completed the first circumnavigation of the Earth after Magellan’s death. Inexplicably not deterred by his harrowing first voyage around the world, Elcano eventually died of scurvy in the middle of the Pacific. However, in recent years considerable attention has been given to de Hoces, who commanded a ship called the San Lesmes. At the time, Europeans were unsure of how far south Tierra del Fuego extended and only knew how to reach the Pacific through the Strait of Magellan. But de Loaisa’s expedition was caught in a terrible gale just as they reached the mouth of the Strait. The San Lesmes was separated from the rest of the fleet and blown toward Antarctica, apparently to a latitude of 56 degrees south. That would make the crew of the San Lesmes the first Europeans to see the open ocean south of Tierra del Fuego. De Hoces was able to rejoin the expedition, only to be separated by yet another gale once the fleet had passed through the Strait of Magellan. This time, the San Lesmes was never seen again. It also largely vanished from history until 1975, when the Australian writer Robert Langdon proposed a sensational theory. Three 16th-century Spanish cannons had been found on Amanu Atoll, east of Tahiti, and Langdon suggested that they were probably from the San Lesmes. In Langdon’s theory, de Hoces dumped the heavy cannons on Amanu and then journeyed to various Pacific islands, intermarrying with the locals and introducing Spanish culture. He then made a bold attempt to sail back to Spain, but was blown off course to New Zealand, where he settled, creating a number of Maori legends in the process. Of course, Langdon’s theory remains extremely controversial among historians, who continue to regard the fate of the San Lesmes as a mystery.

3Everett Ruess

The wilderness of the American southwest proved an irresistible draw for the great boy-poet Everett Ruess. A writer and artist as well as a poet, Ruess entered the wilderness when he was just 16, declaring that “I prefer the saddle to the streetcar and the star-sprinkled sky to the roof, the obscure and difficult trail leading into the unknown to any paved highway.” For the next four years, he drifted through the most remote parts of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. To raise money, he sold paintings of the scenery, which are now considered some of the most evocative images of the region. He explored the Colorado Plateau, the High Sierra, and even the Yosemite and Sequoia national parks, communicating with his family via infrequent letters dropped off at isolated trading posts. In November 1934, Ruess was seen leading two burros near Davis Gulch canyon and the Escalante River. He is believed to have died shortly afterward, but nobody realized anything was wrong for four months, at which point his parents began to grow alarmed. The lovable vagabond was never found. In 2009, it seemed like the mystery might have been solved when National Geographic declared that human remains discovered in the Utah Desert belonged to Ruess. The magazine cited a Navajo oral tradition that Ruess had been killed by three Utes and DNA testing seemed to confirm that the bones were his. However, further testing revealed that the bones almost certainly came from a Native American, leaving Ruess’s last resting place unknown. The poet himself seemed to anticipate such a fate would be the result of seeking “the wildest, loneliest, most desolate spot there is.” In one of his last poems he famously asked that the world “say that I starved; that I was lost and weary; that I was burned and blinded by the desert sun . . . but that I kept my dream!”

2George Bass

A naval surgeon by profession, George Bass is considered one of Australia’s most significant maritime explorers, having sailed a whopping 18,000 kilometers (11,200 mi) exploring the country’s coastline. His mysterious fate in the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean remains one of the most dramatic watery disappearances in Australian history. Arriving in New South Wales in 1795, Bass teamed up with a sailor named Matthew Flinders to chart the coast of the strange new continent. Unfortunately, the sturdy ship they might have hoped for wasn’t available in the fledgling colony, forcing them to use a tiny skiff dubbed the Tom Thumb, which was barely larger than a bathtub and definitely not designed for the open sea. In this rickety dinghy, the pair explored the coast south of Sydney. After recruiting a slightly larger vessel, they made it all the way to Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen’s Land). On this voyage, Bass became the first European to realize that Tasmania was actually an island, which remains a major breakthrough in the study of Tasmania. As a result, the body of water separating Australia and Tasmania was named the Bass Strait in his honor. In 1803, Bass set out from Sydney with a ship full of cargo he intended to illegally sell in Spanish South America. After many months, the realization dawned that the expedition had been lost. The likeliest explanation is that the ship was wrecked in a storm, although a popular theory holds that he was captured and sent to work in the Spanish silver mines in Peru.

1Henry Hudson

Back in the early 17th century, it took an extraordinarily courageous soul to venture into the icy unknown of the Arctic. But the British explorer Henry Hudson didn’t hesitate to sail the region in search of the fabled Northwest Passage that would allow European ships to reach the Indies via the Arctic. As it turned out, Hudson probably should have hesitated at least a little bit. Ironically, Hudson actually started his exploration career by searching for the equally fictional Northeast Passage, an ice-free route to the East through the Russian Arctic. Sponsored by the English Muscovy Company, Hudson undertook voyages in search of this route in 1607 and 1608 but was stumped by the ice fields near the Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya archipelagos. The Dutch East India Company then hired Hudson for a third try, but the winds proved unfavorable and Hudson talked his crew into heading for North America instead, where they explored what is now the Hudson River. Encouraged by his first trip to the Americas, Hudson returned to England to secure backers for an attempt to find the Northwest Passage. The expedition set sail in 1610 aboard the well-equipped Discovery, and the crew members were hopeful as the ship entered what is now the Hudson Strait and bobbed right into Hudson Bay. A winter spent in the icy waters of Northern Canada soon changed their minds, and many crew members were desperate to get home in the spring. Hudson didn’t improve morale by behaving indecisively and playing favorites—like when he gave a warm robe to one crew member and then demanded it back to give to someone else. When a rumor spread that Hudson was hoarding food for his favorites, the situation turned ugly. According to accounts from the surviving crew members, a mutiny was led in June 1611 by Henry Green and Robert Juet. Historians consider this account suspicious, since both Green and Juet were killed by Inuit on the way back, making them ideal scapegoats for the mutiny. The English authorities were probably happy to play along with this version of events, since the survivors had valuable knowledge that made them too important to execute. Notably, the survivors were charged with murder, which they were ultimately acquitted of, rather than mutiny, a charge of which they were definitely guilty. However the mutiny happened, Hudson’s fate is clear. He and eight others, including his young son, were set adrift in a small boat in the frigid waters of Hudson’s Bay. As the Discovery sailed away, Hudson’s little boat desperately rowed after it. But the oarsmen tired, and the Discovery piled on more sail to move out of sight. The bodies of the marooned nine sailors have never been found. Malavika Madgula is a freelance writer and blogger. When not obsessed with the disappearances of people, she blogs at malavika24.wordpress.com. You can also write to her on Twitter.