10 Bizarro Fiction

If we’re going to talk about bizarre literary movements, then we have to discuss the up-and-coming genre that is bizarro fiction. Self-described as “literature’s equivalent to the cult section at the video store,” bizarro fiction prides itself in offering readers the finest in fun, low-brow weirdness. Such weirdness has proven successful with its target audience of weird readers, receiving praise from famous literary oddities like Chuck Palahniuk. The movement began officially in 2005, when three independent publishing companies by the names of Eraserhead Press, Afterbirth Books, and Raw Dog Screaming Press tapped into a strong demand for bizarre and unusual fiction. At this point, the movement had no specific name or definition, but there was a general feeling that a new genre of weirdness was on the horizon. This genre became bizarro fiction. Nowadays, the cult movement has a dedicated following of readers, along with its own annual convention, aptly named BizarroCon. Bizarro fiction might find inspiration from such high-brow names as Franz Kafka, William S. Burroughs, and David Lynch, but the offbeat movement favors fun and silliness over pretentiousness and literary art. Such silliness can be found in some of bizarro fiction’s most popular titles and plotlines. Satan Burger by Carlton Mellick III—an author described as the Johnny Appleseed and Johnny Rotten of Bizarro—is a novel in which God’s hatred of man leads Him to repossess people’s souls and place them into a “large vagina-like machine called the Walm.” In place of human beings, God propagates the Earth with a new, insane, sex-obsessed, and super-powered species that destroys the Earth. Meanwhile, in Kevin L. Donihe’s House of Houses, a man falls in love with his house until a “house holocaust” occurs the day before their wedding. Typical. Other similar Bizarro titles include Adolf in Wonderland, You Are Sloth!, and Shatnerquake (in which William Shatner is hunted by all of his past characters).

9 Oulipo

A more artsy movement than Bizarro originated in France during the 1960s, founded by French writers Raymond Queneau and Francois Le Lionnais. The movement began with a group of writers called the ouvroir de literature potentielle, roughly translated as “the workshop of potential literature.” This was then shortened to oulipo. What made oulipo unique in its approach to literature was its belief in applying constraints to the writing. The oulipo belief was that too much freedom stunted inspiration, while more constraints encouraged it. What resulted was a number of interesting writing techniques, generally founded upon mathematical problems and equations. One of these techniques was known as the “S+7 technique.” This involved replacing a text’s nouns with the seventh noun that follows it in the dictionary. The results were often a series of increasingly bizarre and hilarious sentences. The S+7 technique can work for any sentence with nouns. For instance, a sentence could begin as: “Hello, my name is Nathaniel Woo. I’m a writer for Listverse.” Each noun would then be replaced with the seventh noun following it in the dictionary, resulting in: “Helm, my namesake is Nathaniel Woo. I’m a writing for Listverse.” Doing this once again would then make the sentence become: “Helmet, my nanny is Nathaniel Woo. I’m a wrongdoer for Listverse.” As well as bizarre writing techniques, the oulipo movement gave birth to some interesting pieces of literature. Oulipian work included the likes of Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style, in which the same mundane story was told 99 times, each in a different style. The styles ranged from being completely metaphorical, being rewritten as a haiku, and being written in the style of a blurb. Another oulipo writer called Georges Perec was known for writing the novel A Void, in which the letter “e” is never used, as well as the novella Les revenentes, in which the letter “e” is the only vowel. Those oulipo guys sure knew how to have a good time.

8 Ero Guro Nansensu

It should be no surprise that a slice of Japanese culture has been included in a “bizarre” list. Time and time again, Western audiences have been bemused by unusual Japanese artworks, films, or even commercials. Little did we know that many of these bizarre elements were influenced by a movement in Japanese art and literature called ero guro nansensu. The name of this movement is a Japanese mixture of the English words erotic, grotesque, and nonsense. And erotic grotesque nonsense is exactly what ero guro is. The movement garnered mainstream popularity in the 1920s and 1930s, between World Wars I and II. Much of the movement’s art and literature was characterized by large amounts of sexual obscenity and graphic violence. One particularly popular writer of ero guro fiction was Edogawa Rampo, a Japanese writer of crime stories who often focused on erotic and decadent elements. For instance, one of Rampo’s novels, The Human Chair, focused on a man who hides inside an armchair because he enjoys the feeling of women sitting on him. More disturbingly, Rampo’s The Caterpillar told the story of a gravely injured war lieutenant who had all of his limbs amputated, forcing him to crawl along the ground like a caterpillar. The lieutenant’s wife is both disgusted and aroused by his injuries, so she decides to play sadistic sexual games on his limbless body. Charming. Ero guro’s legacy is far-reaching, with many of its conventions still being prevalent among Japanese manga and anime. That probably explains all the weird tentacle stuff.

7 ‘Asperger’s Realism’

The term “Asperger’s realism” is not so much the name of a movement as a rather insensitive label attached to particular writers within the broader movement of “alt lit.” By far, the two most prominent writers of this brand of literature are Tao Lin and Marie Calloway. These American writers rose to fame in their early twenties through their online personas and publications. Both writers became known as “Asperger’s realists” through their emotionless and somewhat robotic tones of narration. The “realist” elements of their work came from a blurring of fact and fiction, especially in relation to the writers’ personal lives. Marie Calloway’s Adrien Brody highlights this blurring of fact and fiction perfectly. The short story was originally published on Tao Lin’s website Muumuu House, telling the tale of an affair between the 21-year-old Calloway and a married, 40-year-old writer. It wasn’t long before the story blew up within literary circles and caused mass controversy, due to the 40-year-old writer’s identity being easy to guess for industry insiders. (She didn’t actually have an affair with Adrien Brody.) Eventually, the story featured as part of Calloway’s what purpose did i serve in your life, a collection of short stories comprised of Facebook Messenger screenshots, e-mails, texts, and explicit photographs, all of which detail Calloway’s sexual history. While the content is not as offbeat as bizarro fiction or oulipo, alt lit and Asperger’s realism earn their places on this list through their unique uses of the Internet and their odd relationships with reality. The lives of alt lit writers are also generally quite bizarre. Tao Lin alone has been known to spam newspapers with ironic e-mails, interview and write about himself in feature articles, sell shares of his own novels to the public, and dabble in dangerous amounts of drugs. Of course, most of this behavior ends up as content for Lin’s books somewhere down the line. His latest novel, Taipei, discusses much of Lin’s experiences with drugs. The book earned a hilariously backhanded compliment from Brett Easton Ellis: “With ‘Taipei’ Tao Lin becomes the most interesting prose stylist of his generation, which doesn’t mean ‘Taipei’ isn’t a boring novel.”

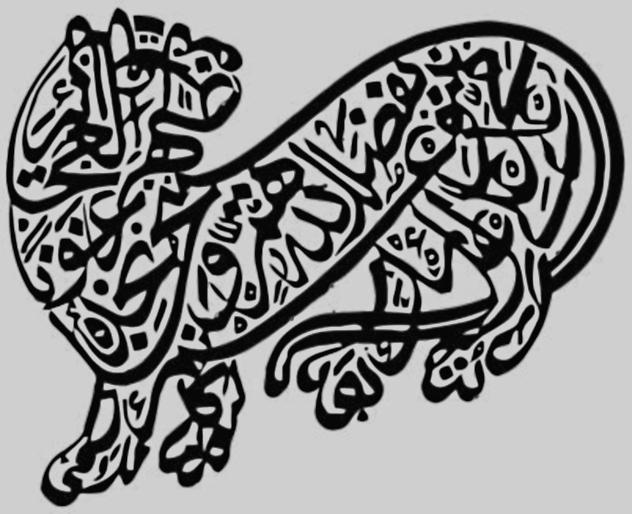

6 Calligram

French poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire first gifted calligrams to the world when the poetry collection Calligrammes was published shortly after his death in 1918. The aim of the calligram was to write a poem in which the letters were structured to take the form of an image that depicted the poem’s meaning or subject matter. Featured in Calligrammes were various poems that took the form of recognizable images, from horses to the Eiffel Tower. The latter example was striking for the way that it assumed the voice and appearance of the Eiffel Tower, while the poem’s words attacked and mocked the Germans, with whom France was at war during World War I. Since Apollinaire’s initial collection, artists and writers have gone on to create visually impressive calligrams of tremendous detail. As a result of this visual appeal, calligrams have proven to be useful within modern culture. In particular, many elementary schools have used calligrams to encourage young people to become engaged with poetry from an early age. The simple language and visual attraction of calligrams has made this genre more appealing to young children than the Romantic poems of Byron or Shelley. And many fans and fandoms have already written calligrams in the likeness of their favorite celebrities, such as Jimi Hendrix, Freddie Mercury, and Audrey Hepburn. Why not give Benedict Cumberbatch a try?

5 Dada

Although more famous for its visual art than its literature, dadaism was an experimental movement that began in the early 20th century. Dadaism is difficult to define, but the movement was largely viewed as a reaction against World War I. Being founded in neutral Switzerland, dadaists were of the belief that the self-interested ideologies of capitalism, nationalism, and colonialism were responsible for the global war. As a result, dadaism focused on going against what these dominant ideologies viewed as rationality and logic. Most dadaist art and literature therefore exhibited a sense of chaos and anarchy. This chaotic rejection of conventional artistic beauty meant that dada was labeled as a kind of “anti-art.” In other words, dadaist art was art that rejected and questioned what art is and how it can be defined. When applied to literature, the most well-established form of dadaist writing was the cut-up technique. Despite being made popular by William S. Burroughs in the 1950s and 1960s, the cut-up technique originated much earlier with the dadaist movement. In fact, the dadaist leader Tristan Tzara outlined the methods of his cut-up technique in his 1920s text How to Make a Dadaist Poem. Tzara’s technique involved cutting out the words from a newspaper article, shaking the words in a bag, picking the words out of the bag, and then structuring them into a poem. This technique meant that the cut-up poem would lack the human logic of a writer’s decisions, as the random selection of existing material made the poetry anarchic. The most famous modern user of the cut-up technique is David Bowie, who is known to use the technique when writing song lyrics. After World War I, dadaist literature began to branch off into the equally bizarre surrealist movement. Wishing to create new art, rather than react against established creations, Andre Breton decided to use the technique of automatic writing. This technique involved writing non-stop and without thought, thus allowing the subconscious to shine through. Such writing resulted in Breton’s The Magnetic Fields, marking the end of literary dadaism and the beginning of literary surrealism.

4 Asemic Writing

When we think about literature and writing, we often think about words. But asemic writing is a type of writing that doesn’t involve any words at all. It merely involves a bunch of pretty squiggles. Asemic writing is designed to have no specific meaning. In fact, the term “asemic” derives from a condition called asemia, sufferers of which are unable to understand signs and symbols. This meaningless state is achieved through writing in nonexistent languages. This isn’t to say that asemic writing is totally meaningless or incomprehensible. On the contrary, the abstract and unreadable nature of asemic writing enables it to be broadly interpreted as having multiple different meanings. In this sense, asemic writing can be seen to establish a universal language that is accessible to all nationalities and cultures. Also, asemic writing can be viewed as capturing and reflecting emotions that cannot be fully explained through words. It can be pretty neat stuff, or it can be meaningless rubbish. It’s really up to you. Similar to the calligram, asemic writing can be viewed as an art-literature hybrid. The genre’s nonspecific nature means that the appearance of the writing is important. Essentially, good asemic writing has to be made of attractive or striking scribbles, not just the messy handwriting of a two-year-old. (Unless you really like the messy handwriting of a two-year-old, of course.) This focus on appearance often results in asemic writing looking similar to calligraphy. In fact, some of the oldest recorded asemic writing is Chinese calligraphy from the eighth century. Specifically, the calligrapher “crazy” Zhang Xu was famous for his bizarre cursive calligraphy. It was all twiddly, squiggly, and rather pretty but nearly impossible to read. The calligraphy of crazy Zhang has been noted as an influence on asemic writing practitioners like Tim Gaze and Michael Jacobson, both of whom run asemic writing publications like The New Post Literate and Asemic Magazine. To these asemic writers, the movement is an important contemporary development that can progress and evolve conventional written language.

3 Flarf Poetry

Flarf poetry earns extra points for having a funny name. The term “flarf” was created by a group of poets who communicated through an e-mail listserv. “Flarf” or “flarfiness” was used by the group to describe anything that could be deemed as inappropriate or politically incorrect. The first ever flarf poem occurred when Gary Sullivan decided to send the worst and most offensive poem possible to a scam poetry contest. The poem began: Mm-hmm Yeah, mm-hmm, it’s true big birds make big doo! Of course, it still won the fake contest. Sullivan then encouraged other writers on the listserv to send their own bad poems to the contest. This quality of flarfiness then dominated the group’s poetry through the use of Internet search engines. The group would use engines like Google to explore unusual search terms, with the results being used as lines or subject matter for their bizarre poetry. A few snazzy examples of flarf poetry include Mel Nichols’s poem I Google Myself, in which the term “Google” is frequently used as a sexual innuendo. K. Silem Mohammad’s Led Zeppelin Experience consists of content from Internet forums, opening with the line: “what are you retarted [sic] making fun of dead people?” While the whole thing seemed like a joke, the 21st-century movement proved to be a big talking point in the literary world. It was discussed in publications like The Atlantic and The Wall Street Journal. At one point, the movement even had its own festival. But for obvious reasons, the movement caused controversy. The use of existing material from the Internet, as opposed to the poet’s own imaginative phrases or images, was seen by critics as an attack on what “true” poetry is. There were arguments that it might have even been plagiarism, while some criticized flarf for its reliance on the problematic practices of Google. Other critics, like Kenneth Goldsmith, viewed it as a progressive movement, much needed in the new Internet age. Of course, Goldsmith was the same guy who read out Michael Brown’s autopsy report as a poem.

2 Spoetry

Speaking of the Internet age and funny names, spoetry was another movement similar to flarf poetry. But rather than unusual search term results, a spoet’s literary muse was the contents of their spam e-mails. The results were often hilarious. For instance, a spoem featured in The Guardian began: When she was first over and over again She rubs everything that can be rubbed, until It was originally, I think, eight thousand pounds, Consol? Utterly bizarre. These spoems derived from the infamous “spam lit,” which was the nonsensical content found in old spam e-mails. Generally, this bizarre spam lit came from excerpts of classic prose or poetry, often aimed at bypassing spam filters. While most of us have encountered spam lit, few of us have had the nerve to turn it into poetry. The spoets, however, were not like us. These special writers could see the beauty behind the half-priced Viagra and penis-enlargement deals. Some writers merely copied and pasted the beauty and rearranged it into stanzas, while others edited the nonsensical spam lit into coherent verse. Either way, spoetry was born. Much like flarf poetry, spoetry garnered widespread interest. Ever since Satire Wire held their first spoetry contest in 2000, established writers continued to publish entire anthologies of spoetry. English writer Ben Myers published an anthology titled Spam (Email Inspired Poems) in 2008, and the contemporary US poet Endwar released a book called Machine Language, Version 2.1 in 2006. Along with Endwar’s book, a CD was included, where spoems were read out by the automated voice of Microsoft Sam. Spoetry shares a lot in common with some of the more classically accepted movements on this list. The act of cutting and editing existing content from spam e-mails is basically a 21st-century adaptation of the dada cut-up technique. Even the constraint of using purely spam lit seems like an Oulipian method. Is spoetry often a load of nonsense? Absolutely. Is it poetic nonsense? Undeniably so. In the words of Monty Python: “Spam, spam, lovely spam, wonderful spam.”

1 Ergodic Literature

With the increase in free open-world games like Grand Theft Auto V and The Witcher 3, ergodic literature is perhaps the most relevant literary genre of modern times. In brief, ergodic literature is when the reader is an active participant in the construction of a text. Similar to how a gamer’s personal actions and choices affect a game’s narrative, the way that a reader chooses to read an ergodic text alters the reading experience. Conversely, a traditional, non-ergodic text has a fixed narrative, directed purely by the narrator. An example of ergodic literature can be found in S., a novel by Douglas Dorst and J.J. Abrams, in which there are two alternate plots. One of the plots takes place in the novel’s main text, while the other is handwritten in the margins. Physical documents relating to the different plots are also included to make the text even more immersive. The potential of ergodic literature has been noted by the likes of Salman Rushdie, who discussed Borges’s The Garden of Forking Paths as a potential model for the progression of literary storytelling. In The Garden of Forking Paths, a fictional writer attempts to compose a novel in which all the potential outcomes of a decision are described, leading to multiple “forking paths.” This idea of forking paths has become the basis for a lot of ergodic literature in which different events might occur through different reading choices. There have been various ergoidc texts that have followed this forking paths model. Our Oulipian friend Raymond Queneau explored this type of literature through constraint in his collection, A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems. This collection is a set of 10 sonnets, with each line being written on a separate piece of card. Since all of the poems share the same rhyme scheme and sounds, all of these lines can be mixed and matched. The result is a potential 100 trillion (or 100,000 billion) variations of the same sonnets, depending on the reader’s choice of lines. It would allegedly take 200 million years to read every single combination. Along a similar vein, Marc Saporta’s Composition No 1 is a novel comprised of 150 separated pages. The fragmented nature of the book allows the reader to structure and read the book in any order they please, with each order producing different results. Be careful though, it’s a box full of loose paper, not exactly perfect for light lunchtime reading. Nathaniel Woo is an English writer and student at the University of East Anglia. When he is not blogging or Tweeting about tennis, Nathaniel is either reading or writing short stories.