Yet it’s the combination of the mundane and the terrible—once you know it’s there—that is most arresting. Some photos’ stark simplicity becomes haunting when you realize the true story underneath.

10 The Fredericksburg Ice House

This image seems to be merely a pastoral view from the 19th century. It’s only marginally more interesting to hear that this is a view of the famous Fredericksburg battlefield, a couple of years after thousands of Union soldiers fell there during the US Civil War. It seems unremarkable—after all, the soldiers are all gone. Or are they? After the fighting, Union troops were in a rush to dispose of their dead comrades during a brief truce. The cold December weather made digging hard, and eventually, the gravediggers got tired. They looked around for any other place they could stash the bodies. Their eyes settled on the abandoned icehouse of a Mr. Wallace. That’s the long, low building in the right foreground. With little ceremony, the burial details began dumping their deceased brethren inside. The sight sickened several onlookers. One soldier described the scene: [They would] drag the bodies to the pit of an old ice house, 15 feet deep, and cast them, all turned and twisted and doubled; the feet of one sticking up, the head of another, the arms and back of another; the upturned faces, beside the protruding entrails. Hundreds were to be thrown in, and what a horrid spectacle the whole mass would present, the imagination must picture. An officer recalled: The most sickening sight of all was when they threw the dead, some four or five hundred in number, into Wallace’s empty icehouse, where they were found—a hecatomb of skeletons—after the war.[1] After that, the armies eventually moved on. The populace had fled. The city remained a ghost town for the rest of the war—in more ways than one. No one remembered what lay behind the icehouse’s rickety door. When the photographer took this image two years after the battle, he had no idea how many decomposing corpses were right there under his nose.

9 The Lawson Family Portrait

Nearly everyone’s been in a family portrait at some point. This photo looks quite run-of-the-mill. Most of the family members look fairly wooden—though the father standing at right has a certain far-off look in his eye. His name was Charles Lawson. And he was already planning on murdering everyone around him. The Lawsons were a poor family, eking out a meager living as tobacco farmers in North Carolina. Their poverty must have weighed heavily on Charles’s mind. Another factor in his disquiet was that he had incestuously impregnated his daughter Marie (back row, second from left)—and she’d started confiding that fact in the neighbors. A week before Christmas 1929, Charles finally decided to pay for a family portrait, because he knew he wasn’t going to need the money.[2] On Christmas afternoon, the father hid in the barn with a 12-gauge shotgun and lay in wait for his daughters Carrie (front row, far right) and Maybell (front row, second from left) as they walked to their uncle’s house. He blasted them at point-blank range, then finished them off with the butt of the gun. Stalking back to the house, he gunned down his wife Fannie (back row, standing far right) on the front porch. The he charged into his own home as an invader. As Marie screamed, he shot her in cold blood, along with his unborn child/grandchild. The small boys James (front row, far left) and Raymond (front row, second from right) ran for cover, but Charles hunted them down in a macabre game of hide and seek. Last was baby Mary Lou (in Fannie’s arms, top right). He finished her off without wasting a bullet and then killed himself in the woods shortly thereafter. The only survivor was son Arthur Lawson (rear row, far left), who was out of the house at the time. Within seven days, a standard portrait had become the last record of a family about to be destroyed by its deranged patriarch.

8 A Doomed Expedition

All expeditions to the far corners of the Earth are fraught with peril. Many of them, especially in the early days, never even reached their destinations. The Terra Nova Expedition, led by British captain Robert Falcon Scott, was one that did. He and four others had set out to reach the South Pole in late 1911 and succeeded. The photo should be recording a moment of triumph, yet there is no elation. Instead, the men look haggard. Despair settles on their furrowed brows. They are haggard from their rough journey. They are joyless because they know it was a race between British and Norwegian teams to reach the pole first, and they’d lost. They are hopeless because the return trip seemed an insurmountable obstacle. It was. The Norwegians were long gone and could be of no help. The group had already endured punishing blizzards and food shortages on the southward journey; returning north would mean similar hardships, with less energy and fewer supplies to sustain them. Each man in this photo had little to look forward to in his short time remaining, just cold, misery, and the real possibility of death. They marched on for weeks, slowed by multiple cases of severe frostbite. Poor weather hampered their progress even further, as did time-consuming searches for pre-established supply dumps that were far too well-hidden. Two men died along the way; the last three made it within 18 kilometers (11 mi) of a resupply camp before perishing. What’s more, they knew how close they were but were unable to reach it. As Scott wrote in his diary’s final entry: Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. R. SCOTT. For God’s sake look after our people.[3] When a belated rescue team found the last campsite eight months later, the corpses of the polar team still lay in their sleeping bags. Their camera was with them. It surrendered this photograph only after all its subjects were long dead.

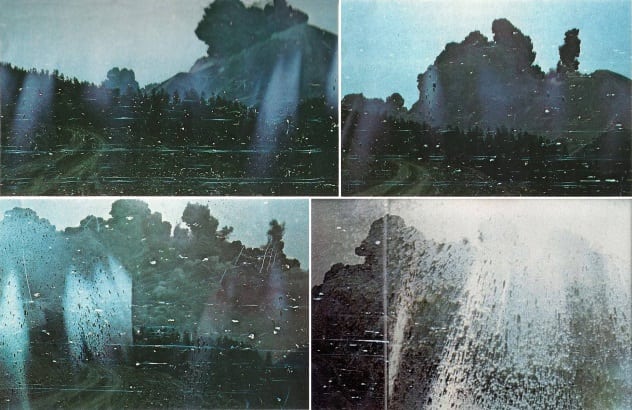

7 A Storm On The Mountain

The photo quality here looks awful, like the above images were shot on an early flip phone. At first glance, it seems nothing more than someone’s grainy camping photography, perhaps depicting some bad weather. In reality, the camera was top-notch, and it was capturing some of the worst “weather” in Washington state history. In 1980, Mount St. Helens in the southwestern part of the state was a slumbering volcano that had decided to stop hitting “snooze.” It rumbled and smoldered ominously for months on end. Yet some people remained in harm’s way. Local residents refused to evacuate, including a famously cantankerous old innkeeper. Geologists and volcanologists, despite their misgivings, stayed close by to monitor activity. And some photographers, eager to document the foreboding phenomenon, crept closer to the stirring giant. One of these was Robert Landsburg. A freelancer supporting National Geographic, Landsburg was on the latest of numerous trips to the mountain. His morning on May 18 began like any other. Waking in his serene campsite, he found a good vista and started snapping photos. But at 8:32 AM, everything changed. A 5.1-magnitude earthquake sent a terrifying landslide down the side of the mountain. Moments later, an eruption of magma, volcanic gas, and ash followed, a one-two punch of rapidly approaching terror.[4] Simultaneously enthralled and horrified, Landsburg kept shooting. It didn’t take long for him to realize that he could never outrun the onrushing blast. Resigning himself to his fate, Landsburg calmly finished his work, dismounted the camera from the tripod, stuffed it into his backpack, and then laid down atop his equipment. His body would protect the precious film. Fifty-seven people died that day, Landsburg among them. But his jaw-dropping final photographs survived.

6 Tropical Tranquility

This image looks like mottled old-time footage, perhaps an old VHS tape of a seaside vacation. Beachgoers wade in the shallows, a familiar sight on any coastline. A second look shows that the breakers beyond the shallows look rather . . . large. They are. When these waders ventured out, they didn’t know they were wading into the path of destruction. Indonesia’s and Thailand’s western coasts in 2004 were densely populated, chock full of everyone from native fishermen to foreign sightseers. Christmas passed peacefully and uneventfully. The following day, however, a gargantuan offshore earthquake unleashed a terrifying tsunami. Experts estimate that the tsunami’s energy was double that of all the bombs used in World War II, combined. As often happens, the tidal wave was preceded by a drainage effect, as water was sucked away from the beach to feed the growing wall offshore. Tragically, many people on the coast mistook this for a sort of benign natural occurrence. Hundreds stuck around to watch. Some even reveled in the unusual circumstance, walking out onto the former seafloor and picking through old junk or stranded fish. When the water returned, it swept all before it. An approximate death toll climbed to nearly a quarter of a million people.[5] Some of the first were the folks in this picture, who had only minutes or seconds to live when it was taken.

5 A Skyline’s Last Morning

September 11, 2001, has passed into the history books, but each living witness has had the day’s events burned into his or her memory. The world changed for many. Western countries awoke to modern realities of terrorism, and nations the world over would be shaped by their response. Approximately 3,000 lives ended, and the loss reverberated throughout countless families, friendships, and workplaces. Most visibly, New York City’s iconic skyline was forever altered. Photographer David Monderer loved that skyline, and he’d been waiting nearly a month to do it justice with a good photo. The sunny Tuesday morning offered the perfect opportunity. He strode out onto the Manhattan Bridge walkway, aimed, and took this shot.[6] The photo above is one of the very last to show the Twin Towers as they were. Looking at the image, it is easy to imagine the activities inside—people beginning their daily routines, fortifying themselves with coffee for the first morning meetings. They had no idea that the cloudless blue sky above already held two airliners winging their way closer, bearing a deadly destiny.

4 An Alaskan Vacation

The man in this photo looks scruffy but perfectly at ease. Behind him is an abandoned Fairbanks bus, signifying the location as Alaska. One might think he’s a local goofing off, or maybe a tourist who found a good photo op. One would not guess that he was slowly starving to death. His name is Christopher McCandless. The unassuming man is actually rather famous as a free spirit, being the subject of a book and film called Into the Wild. Proclaiming his desire to throw off the shackles of modern society and live authentically, he struck off into the Alaskan hinterlands in spring 1992. There, he could commune with nature. Unfortunately, nature showed no desire for communion. Without adequate training or supplies, McCandless was in over his head from the start. He managed to forage for some edible plants and was occasionally successful in hunting attempts, but even these were of limited use to someone who had no idea how to properly preserve the food he gathered. After three months, he tried to hike back to civilization but found the trail blocked by a swollen river. Defeated—and unaware of another viable crossing point less than 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) away—he returned to the bus and settled in to meet his fate.[7] When a hiker found McCandless, the man had been dead for approximately three weeks. His emaciated body weighed only 30 kilograms (66 lb). Stashed away amid his meager possessions was an undeveloped roll of film, from which the above image was recovered.

3 More Northern Serenity

Staying in Alaska, we fast-forward to 2003. Here, we see a happy couple perched on the pontoon of a seaplane, obviously ready to enjoy a wilderness adventure. They got more than they bargained for. The man’s name is Timothy Treadwell, a zealous environmentalist. He had traveled to Katmai National Park with his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, for a pet project: documenting grizzly bears. Treadwell held a strong affection for the beasts and felt them to be kindred spirits. It amounted to a more extreme version of Christopher McCandless’s desire to be one with nature—while McCandless was willing to hunt to survive, Treadwell expected to coexist peacefully with all the animals he encountered. Previous visits had convinced him that the bears would become used to his presence, see him as nonthreatening, and leave him alone. He was tragically mistaken. On October 6, 2003—scant days after this picture was taken—Treadwell and Huguenard’s campsite was invaded by a hungry brown bear. First Treadwell, then his girlfriend were mauled by the remorseless attacker. They may have been still alive when the animal began devouring them.[8] This image is the last known picture of the couple. But it’s not the last record. Treadwell’s video camera was still running when the attack took place. Only audio was captured—a flurry of agonized cries and dying screams.

2 An Army’s Last Exercises

Here, we see quite an archaic throwback: cavalry. These horse soldiers look like they hail from the 19th century. However, this picture was taken in 1939. The men are Polish soldiers, and they unknowingly stand on the precipice of disaster. As part of regular military exercises, all Polish servicemen would practice maneuvers and operations. The cavalry’s role was to act as scouts and skirmishers, fighting on foot when necessary. Many of the men here might have been nervous about rising tensions with Germany but felt confident that Britain and France, Poland’s allies, would swiftly send aid to counter any aggression. They were sadly mistaken. The crushing blitzkrieg would strike within a few weeks, and the Western allies would not react in time to stop it. The Polish army would stand alone, fall alone, and then cease to exist. These cavalrymen would be swept away by a tide of tanks and mechanized infantry.[9] In that way, they are emblematic of all the doomed forces of their country—dandelion ghosts staring down a hurricane.

1 Fleeting Goodwill

A handshake is the simplest means we have for signaling peace and friendship. Intended originally to show you weren’t holding a weapon, handshakes evolved into a minimum standard for mutual respect. Here, Archduke Franz Ferdinand warmly grasps the hand of one of his subjects. The date is June 28, 1914.[10] He could not know that, within hours, he and his wife would be dead by an assassin’s bullets. He could not know that their deaths would ignite festering tensions throughout Europe, eventually plunging the continent (and the world) into war. And there’s no way he could have known the effects of that war: the rise of fascism and Comumnism, another world war, widespread societal breakdown, cultural collapse, atomic standoffs, and terrific new tensions that are still rippling through history. As The New York Times put it in 1915: “Those two shots brought the world to arms, and the war that followed has brought devastation upon three continents and profoundly affected two others, and the tocsin has sounded in the remotest islands of the sea.” The reverberations of 1914 remain with us today. It is hard to know what might have happened had June 28, 1914, gone differently; perhaps some flashpoint was inevitable. But the world would surely have been better off if the handshakes had prevailed. David F. Ellrod lives in Maryland with his wife, three daughters, and one very excitable dog. He can be reached on Twitter @DavidEllrod.