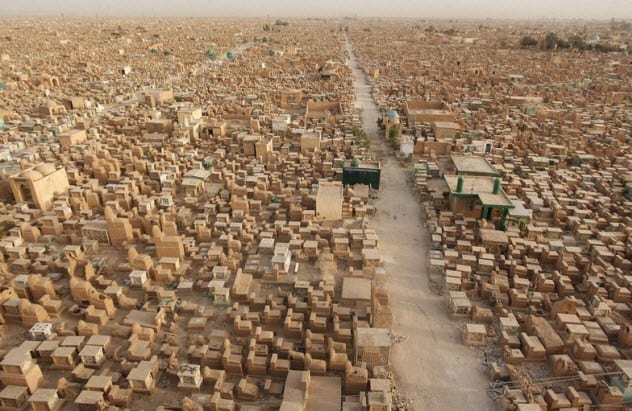

10 Wadi-Us-Salaam

Wadi-us-Salaam (“Valley of Peace”), which contains five million gravesites, is the largest cemetery in the world. This necropolis dwarfs Najaf, Iraq, the city that surrounds it. With a population of 600,000, Najaf is the third most sacred city to Shiite Muslims—after Mecca and Medina. There is a Shia belief that all faithful should be buried at Wadi-us-Salaam, no matter where originally interred. People have been buried in layers there for over 1,500 years in the hopes of being near Ali—first cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad. Wadi-us-Salaam spans more than 8 square kilometers (3 mi2) and is still growing. In 2003, the Iraqi militia launched hit-and-run operations from the necropolis—ambushing enemies and then melting into the shadows of mausoleums and crypts. Ironically, this conflict expanded the graveyard by 40 percent.

9 The Scavi

Hidden five stories under St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City is the Vatican Necropolis (“Scavi”), a massive underground cemetery complex built around the bones of St. Peter. He was martyred in Rome during the reign of Nero. The complex contains three levels spanning between 27 BC and AD 476. There are first-century pagan graves as well as fifth-century sites with Christians buried alongside pagans. The streets of the necropolis are exact analogues for those of ancient Rome except there are tombs instead of stores and residences. In 1965, archaeologists claimed they had discovered St. Peter’s bones when they came across a marker in Greek reading “Peter is here.” St. Peter’s tomb is directly under the central altar and dome of the Basilica. In 2013, Pope Francis became the first pontiff to visit the tomb of St. Peter.

8 Silwan Necropolis

On Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives, one can find the oldest continually used cemetery in the world: Silwan necropolis. The site has been used for three millennia—since the origin of the city. With 150,000 graves, Silwan is significant for the shared faith of its interred. Tradition holds that the Messiah will return to Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives—and those resting on the mount will be the first saved. This city of the dead is a mirror of Jerusalem. In times of conflict, Silwan expands. Although the necropolis sits in largely Arab East Jerusalem, it is considered to be of the utmost importance to Jewish identity. Studies using 21st-century technology are underway to map the location of every grave.

7 Monterozzi

Monterozzi, an Etruscan cemetery complex of 6,000 graves cut into rock, sits in the hills east of Tarquinia, Italy. The cemetery is a replica of an Etruscan town plan. The burial chambers are modeled on the interiors of houses during the period. The site’s vivid art and layout provide a window into the only urban culture in pre-Roman Italy. Monterozzi is famous for its 200 painted tombs, some of which date to the seventh century BC. They are considered “the first chapter in the history of great Italian painting.” The tombs are replicas of Etruscan homes, and their elaborate frescoes depict vivid scenes of life. Art historians believe that ancient Greek painters were lured here by the profitable work of Etruscan tomb painting. Given that we have lost Hellenistic painting to history, experts use these Etruscan examples to extrapolate how ancient Greek painting might have looked.

6 Kiev Pechersk Lavra

Founded in 1051, Kiev’s Pechersk Lavra Monastery sits atop the hills edging the Dnieper River. The monks chose the location because it rests above a vast cave complex, which was used as a burial place for over 700 years. The caves contain the remains of the founder of the monastery—St. Anthony of the Caves—as well as other brothers, monks, ascetics, and saints. The climate and soil mummify the bodies, which are still on display. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, there was a rumor that the cave complex was so vast that it reached from Moscow to Novgorod. Although this is an exaggeration, no one but the initiated knows how deep these catacombs go. Interestingly, the massive cave system includes a museum of microminiatures. Microscopes are required to see Mykola Syadristy’s masterpieces, including a hollowed-out hair containing a miniature rose and the world’s smallest book.

5 Solnitsata Necropolis

North of Provadia, Bulgaria, archaeologists unearthed a necropolis from Solnitsata (“Salt Pit”), the oldest known town in Europe. The site dates to 4300 BC, a millennium before Greek civilization. The tall, thick wall surrounding the town of roughly 300 people suggests that the inhabitants protected valuable resources. It is believed that they sold salt, a valuable mineral that was often used as currency in ancient times. The most intriguing find at the Solnitsata necropolis is a 24-karat gold pendant that is believed to be 200–300 years older than the necropolis. This makes it the oldest processed gold in Europe, if not the world. Similar ancient gold discoveries in the region at the Varna and Tell Yunatsite necropolises suggest the presence of a complex prehistoric society. Skeletal analysis also revealed that the Solnitsata’s inhabitants drank cow’s milk long before any other society.

4 Hal Saflieni Hypogeum

In 1902, a stonemason discovered an underground necropolis on the hill above the Grand Harbor of Valletta, Malta. The Hal Saflieni Hypogeum dated to 4000 to 2500 BC. It is the only known prehistoric underground temple in the world. The Hypogeum is made of three layers superimposed on one another. Builders used stone tools and antlers to tunnel through the limestone. Beyond the 7,000 human remains, artifacts like beads, pottery, amulets, and sculptures shed light on Maltese life of the period. The Hypogeum contains the only Neolithic rock art in Malta. The environment preserved wall paintings of red figures and spirals, which would have faded from existence long ago aboveground. It was believed that burials were conducted in stages. First, the flesh was allowed to rot from the bone, and then the corpses were moved to side chambers and covered with red ocher. Individuals were buried communally with bones stacked atop bones.

3 Necropolis Of Wari Kayan

Between 1925 and 1929, archaeologists led expeditions to the coast of the Central Andes in Peru to explore a city of the dead known as Wari Kayan, which was built by the Paracas culture. Dating back 2,000 years, the site contained 429 naturally mummified bodies in bundles (fardos). The dry air of the Peruvian Andes kept hair, teeth, and flesh intact. The bodies of the Wari Kayan mummies are so well-preserved that scientists have been able to determine their diet: a mix of seafood and terrestrial crops. Magnificent embroidered textiles, some of which took 50,000 hours to complete, are the most significant find in the mummy bundles. The mummies were buried with yards of these masterpieces, which can now be found in museums throughout the world. The elaborate designs offer tantalizing clues into the now-obscure spiritual world of the Paracas culture.

2 Ordek’s Necropolis

Discovered in 1934 on the edge of China’s Taklamakan Desert, Ordek’s Necropolis is a city of the dead spanning from 2000 BC to AD 300. The complex contained roughly 300 mummies buried in what look like upside-down boats covered in cowhide. The dry climate and salty soil preserved the bodies. The most shocking element of the mummies was their non-Asian light hair and tall stature. DNA analysis revealed this population to be of mixed Eurasian and Siberian ancestry. Their plaid textiles suggest the use of a loom—common in Europe at the time but unknown in China. These elements have been used to suggest that they represent the eastern limit of Indo-European speakers and a forgotten chapter in Chinese history. Ordek’s Necropolis also provided the earliest known cheese. Clumps were discovered around the faces and necks of the mummies.

1 Orthi Petra

Located 30 kilometers (19 mi) from Rethymnon, Crete, Orthi Petra provides a window into the Homeric world. The necropolis is part of a larger archaeological site, which was inhabited from 3000 BC to the Byzantine era. The burial chambers of Orthi Petra contain elements lifted directly from the lines of The Iliad, including a funeral pyre dating from 800 BC. Orthi Petra also contains a cenotaph memorial—the first tomb of the Unknown Soldier in history—dated to 670 BC. One of the most intriguing discoveries at Orthi Petra was the burial of four related women. One was 72 years old and believed to be a priestess. The other three were young and believed to be her proteges. All the women were interred with rich adornments, reflecting the island’s prosperous trade with Egypt, Greece, and the Near East. The fact that these women chose to be buried together, without a male, speaks volumes about the sexual politics of ancient Crete.

+ Further Reading

Morbid topics are a mainstay of Listverse so here are a selection of some of the best from our archives. Memento Mori! 10 Incredible Images of Death 10 More Incredible Images Of Death 10 Disturbing Mass Graves Discovered Recently 10 Fascinating Graveyards You Must See 10 Horrifying Premature Burials Top 10 Creepiest Graves Abraham Rinquist is the Executive Director of the Winooski, Vermont, Branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.