The verdict is still out concerning the finest Requiem Mass. Mozart, Verdi, and Berlioz typically land in the top three. There’s no denying, though, that Verdi’s is the most terrifying. In order to write a good Dies Irae section (for which this Mass is legendary), which translates to “Day of Anger,” namely God’s anger during Armageddon, the composer seems to need what Verdi’s wife called “a Mercurial temper.” Short-fused or long doesn’t matter, as long as it burns like Hellfire. Verdi, as is typical with Italians, could make people run out of a room when he got angry. The whole piece is magnificent, and critics like to call it his finest opera. It is not written in one overriding key, but like an opera, changes keys many times. The Dies Irae is by far the most famous section, but his Libera Me, written originally for the death of Rossini, is also glorious, as are the Requiem and Kyrie sections. Not that the other sections are bad. But if Verdi had written only those sections named, and nothing else for his whole life, he would still be remembered as one of the most Catholic and Italian composers ever.

This may be the most titanic concerto for piano in the popular repertoire. Busoni wrote one on an even larger scale, but it is not played as often. It is four movements long, instead of the usual three, and the first is an absolute masterpiece of craftsmanship. The main theme is worked into a passage about halfway through that sounds very similar to the Battle Hymn of the Republic. This is a freak coincidence. It ends with a particularly demanding passage of double trills, in which the fingers of both hands must oscillate in the same direction. Try doing this, and you’ll see that the natural tendency is for the hands to mirror each other. Then the trills become tremolos, all while the entire orchestra is blasting away. The pianist must be very strong to be heard over all the other instruments. The second movement is even more bombastic, and Brahms called it “a little wisp of a scherzo.” The third is well known for a cello solo, and the last is a little more cheerful and jubilant than the first two.

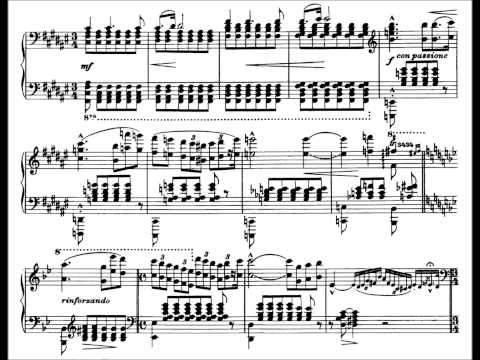

It is the most difficult piano sonata by far, and one of the most difficult pieces ever written for any instrument. Liszt intended it to a magnum opus in terms of technical artistry. Many professional pianists either never perform it, or spend several years practicing it alone, after becoming professionals, before they dare attempt it in a recital. It is one movement, more or less, and lasts about 30 minutes. There are several melodies throughout, and the first is worked through every kind of development possible. In one of the most difficult passages, scale and arpeggio runs in one hand are accompanied by traveling tremolos in the other, very quickly. By the end, there is nothing left to say.

It has been said that Bach and Chopin are the two most idiomatic piano composers in history. Performers of Chopin’s day got word around to him that his music was very difficult for them in some passages, even though they were well versed in all the major composers at that time. Chopin responded by writing these studies for piano technique, not meant to be universal, but meant to train the performer to play Chopin’s style of work. Today, since his music has been so integral in rounding out the Romantic era of music history, his etudes are a bible for up-and-coming pianists. Once they are mastered, a pianist can play anything from the Romantic era.

It may be the single finest piece of chamber music ever written. That competition is among this, Beethoven’s late quartets, and some by Mozart and Haydn. It is four movements, and every movement is a masterpiece, as fresh to hear the 100th time as the first. It has a cyclic structre, the final theme of the last movement being paired with the first them of the first in a double fugue. It is very popular primarily because of its driving, unbridled melodic power, from beginning to end. Even the fairly slow second movement is a funeral march, and thus holds the listener at the edge of his or her seat.

Schumann referred to it as “heavenly length.” Schubert had a bit of a problem ending a piece when he was having fun writing it. This symphony averages about 50 minutes, and encompasses every musical idea and technique for which Schubert was famous: outstanding lyrical melodies that are very well developed, a lighthearted mood, a dark, tragic mood, all in perfectly balanced orchestration.

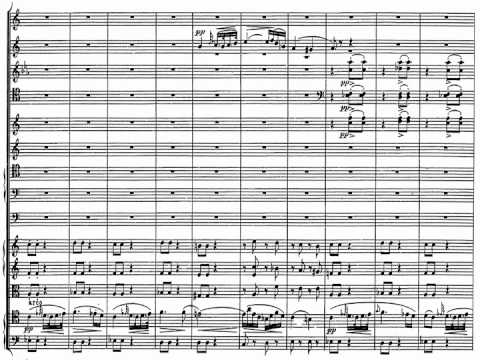

It is the longest opera routinely performed throughout the world, at 6 hours including intermissions. Most operas are 3 to 3.5 hours. Wagner spent 26 years writing the libretti and scores to the four music dramas that comprise Der Ring des Nibelungen. Gotterdammerung is the last of the four, and Wagner collects all the leit-motifs, of which technique he is the famous inventor, into a powerful storyline that must be reduced to its very basics in order to fit in this list. Siegfried, the world’s greatest hero, is by now in love with Brunnhilde. Everyone in the entire world, man and god, wants the ring, and Greed is the uncontrollable element. Hagen, one of Siegfried’s companions, spears him in the back, and later attempts to take the ring from his dead hand. The hand appears to be alive, and so the ring is left on Siegfried’s body. He is burned on a pyre with the ring, and Brunnhilde rides a horse into the flames to die with him. The very final leit-motif in the whole story is Wagner’s melody for “love.” Everything else, man and god, is destroyed. Valhalla burns in the distance. After a performance of this piece, you will wonder if there is any music left to write about anything. It has Siegfried’s famous funeral march and Brunnhilde’s immolation scene at the end.

When Beethoven set his mind to it, he actually made good on his intent to write the best example he could in a particular musical genre. Viewers may have expected his 9th Symphony, and it may be the finest symphony of all time. But in this lister’s opinion, his Solemn Mass is his finest large-scale work. It is not as Christian as it is mystically Deist. Beethoven’s religious beliefs are still debated, but there is no doubt that he believed in God. In the margin of the first sheet of his Gloria section, he wrote, “God above all things!” Every section is a titanic testimony to what he believed in terms of God, Christianity to some extent, Heaven, etc. The work defies linguistic description. It has garnered just about every positive adjective in a language over the years. The most accurate, perhaps, is “ethereal.” The Gloria, for its part, is unbelievably soaring, even moreso than his 9th Symphony. It ends on a 5 chord, the dominant, instead of a 1 chord, the tonic, and this serves to make it sound like something otherworldly, or as if the music never ends, and Heaven’s orchestra takes up where it leaves off.

Wagner called it “the most perfect opera there is.” Impressive coming from him. Wagner was Mozart’s greatest admirer. Don Giovanni is a very simple story of a lecherous fool who enjoys having affairs with any woman who takes his fancy. Some have claimed it to be a self-indictment of the composer, who was something of a womanizer. At the end, Don Giovanni is interrupted during supper by the ghost of a man he killed in order to escape, after having sex with that man’s daughter. The ghost demands him to repent, and Giovanni refuses several times. Demons appear and drag him to Hell. Then the rest of the characters appear in the last scene and perform an ensemble soliloquy making fun of him as a sinner. This opera is the essence of balance, among orchestra, chorus, soloists, even between music and drama. The music typically overshadows the drama, but not in this one, and it’s as mesmerizing and enchanting the thousandth time as the first.

Many musicologists consider it the finest achievement in all of music. Bach never intended it to be performed, but wanted to suit his own curiosity as to whether he had mastered every aspect of music composition at his time. As a result, this Mass has everything Baroque in it: 4, 5, and 6 part choruses, solos, fugues, general contrapuntal mastery par excellence. It is one of the few missa toti in existence, that is, the entire Latin Mass set to music. Most masses, including those by Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, etc., are abbreviated versions of the whole litany. The Mass in b minor, consequently, is one of the longest ever written, requiring about 2 hours to perform. It even incorporates numerology, one of Bach’s hobbies, into its music. The Crucifixus chorus is based on a melody that, when transcribed to a Cartesian plane, forms a cross. The Mass is comprised in large part of cantatas and other sacred works which Bach wrote earlier in his life, and revised for inclusion as a chorus here, a solo there. He wrote several sections expressly for the Mass, and they are among his last works, most of them in the Credo section. If you are not particularly enthusiastic about such complex music, you’ll probably find his glorious Sanctus the easiest to enjoy.