10The Rip Raps

Taking their name from a notorious shoal in the Hampton Roads, the Rip Raps dominated Baltimore in the 1850s. The gang was adamantly anti-Catholic and anti-immigration, a stance that eventually prompted them to lend their support to the similarly inclined Know-Nothing political party. And by “support,” we mean they rioted and burned down the headquarters of the opposing Democratic party (ironically located in the New Market Fire Company Buildings). Democrats who tried to flee the scene were caught and beaten in a bizarre, bloody episode that left two people dead and many others injured. The Know-Nothing candidate won the election. The incident helped set the stage for the 1856 presidential election, which took place just a month later. The Know-Nothing candidate, former president Millard Fillmore, won a runaway victory in the state—it was the only state that he did win—but the power of the Rip Raps couldn’t continue to go unchecked. Even Mayor Thomas Swann, who had been elected with their support, tried to turn the gang away from violence. Meanwhile, Swann used his office to establish a professional police department and fire brigade. By the time the next election came around, the gang had fallen by the wayside.

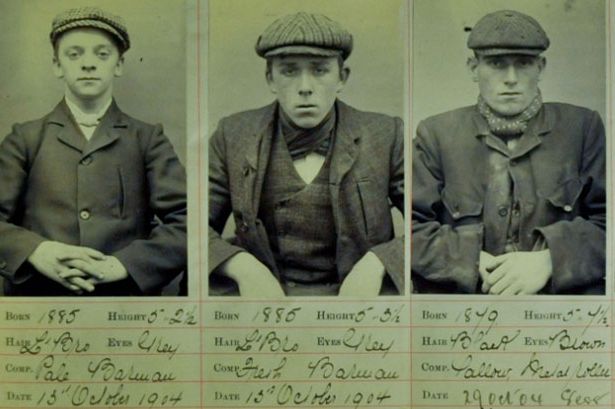

9Peaky Blinders

According to popular legend, the Peaky Blinders were named after their weapon of choice—flat caps with razor blades sewn into the brim. While it’s not clear just how accurate that particular story is, the gang featured in the BBC television series Peaky Blinders was absolutely real. Formed in the poverty-stricken streets of Birmingham, England at some point in the late 1800s, the Peaky Blinders were actually just one of a number of gangs plaguing the city. They were often in the thick of mass street brawls, which could last for hours as rival gangs tried to assert their dominance. Much like the other gangs, they ran protection rackets and targeted anyone who seemed vulnerable. But there was one important way that the Peaky Blinders were different from the other street gangs—they had style. In fact, the Blinders were known by sight, famous for their silk scarves and neat trousers. Like the other gangs, they commonly recruited children into their ranks, with weapon-carrying members as young as 12 or 13 showing up in the Birmingham arrest records.

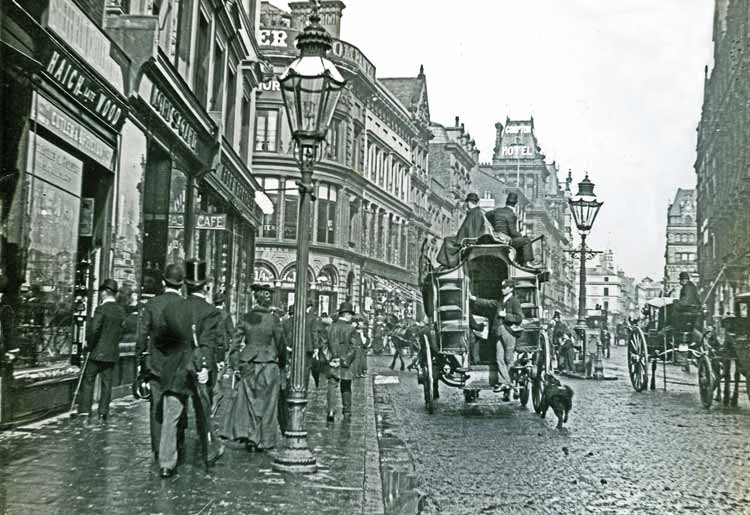

8The High Rip Gang

The High Rip Gang stalked the streets of Liverpool in the 1880s. In January 1884, the body of a Spanish sailor was found in the city, brutally beaten and stabbed in a way that was terrifyingly reminiscent of the murders carried out by a gang that had been operating in the area a decade earlier. A 17-year-old laborer was ultimately found guilty of the murder and hanged for the crime, but the gang’s activities continued. Peaking between 1884 and 1886, the High Rips’ reach spread throughout the poorest sections of the city. Most of their victims were sailors, dockworkers, and shopkeepers. Those they didn’t kill were often left badly beaten and permanently disfigured. The gang’s favorite weapons included heavy belts and knives known as “bleeders.” The High Rips emerged on the heels of a group called “the Cornermen,” who got their name from their tendency to wait on street corners for a victim to pass by. But the High Rip Gang was a much more organized and ruthless force. Members were always armed—so much so that the police preferred to just let them have their way rather than risk a confrontation. While the gang’s activities lessened after 1886, it lingered throughout the rest of the decade. It’s even been suggested that some members had ties to Jack the Ripper.

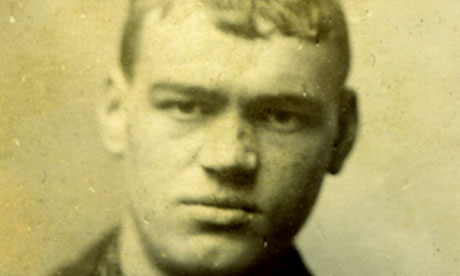

7The Deansgate Mob

Traditionally, history focuses on the conflicts of adults, and the end of the 19th century was a time of huge upheaval in the British empire. But there was also trouble at home. Youth crime was recorded in those days, but finding any trace of those records now takes a fair bit of work. But a researcher from Liverpool recently uncovered a series of records suggesting that Manchester was among the worst, bloodiest places to grow up in 19th-century England—and that’s mostly because of people like John-Joseph Hillier and his Deansgate Mob. The Deansgate Mob had claimed a music hall called “the Casino” as their base, and frequently brawled with anyone brave enough to step onto their turf. Hillier joined the gang when he was just 14. By the time he had scrapped his way to the top, they were firmly established in the center of Manchester. Hillier served a stint in jail for attacking his enemies with a butcher knife, and street-fighting was an extremely regular occurrence. Fights between gangs were called scuttles, and reporters soon christened Hillier “King of the Scuttlers.” He was so happy with the name that he had it sewn on the front of his shirt. It became a regular part of his uniform, along with the sharpened belt buckles that defined scuttler fashion.

6The Forty Thieves

For most of its history, New York was famous as the domain of the street gang—and the Forty Thieves were among the very first. At some point around 1825, the pickpockets and thieves who frequented a certain shabby storefront—one that sold cheap vegetables, cheap food, and even cheaper rum—realized that they would be more effective if they banded together to do their dirty work. For more than 25 years, the mostly Irish gang would function under a system in which members were expected to bring back a certain amount of stolen goods—or face the consequences. And the consequences were faced by everyone, including the wife of the gang’s first leader, Edward Coleman. When she failed to meet her quota, Coleman beat her to death. He was eventually hanged for the crime, but his gang continued to thrive without him. They recruited even younger members, no more than children, and called them the Forty Little Thieves. They served as pickpockets and lookouts, while being groomed to enter the ranks of the older group. For many of the Thieves, crime was a way to pull themselves out of the crippling poverty that blighted New York’s slums. Some even branched out into politics, forming strong ties with the formidable Democratic machine known as Tammany Hall.

5The Bowery Boys

Perhaps the most famous of New York’s Five Points street gangs, there were several different incarnations of the Bowery Boys throughout the 19th century. At times, it’s tough to determine what’s true and what’s not, as the gang were famous for spinning tall tales around their exploits. As early as the 1840s, there were plays being performed in New York’s Bowery theater, telling the probably partially accurate story of Mose Humphreys. Painted as a larger-than-life Bowery Boy on the stage, it’s pretty certain that his real-life career was more along the lines of running protection rackets with his division of the gang. At the time, New York’s fire brigades were largely gang-run—it was common to see competing brigades fighting each other at the scene of a fire. The real Mose had actually met his match during a fire-fight a few years before, eventually leaving for Hawaii to run the same racket there. But while the gang fought in the gutters, they were also a power in the political world. They took up the cause of the little guy, rallying against upper-class politicians and turning elections into riots. For a time, polling places were an incredibly dangerous place to be—but for some, the gang was a mechanism for social reform. When gang leader Mike Walsh died in 1859, the poet Walt Whitman not only wrote about his struggles, but was likely the author of an obituary lauding him for his passion and heart.

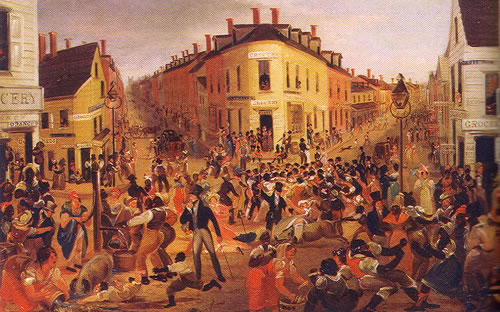

4The Dead Rabbits

First and foremost, the Dead Rabbits were the mortal enemies of the Bowery Boys. According to the stories, both gangs could claim more than 1,000 members by the mid-1800s—so when the two gangs faced off, it was guaranteed to be a legendary clash. Just what kind of scale is accurate is up for debate, but the two gangs certainly ran into each other dozens of times in the 1830s and 1840s alone. According to popular legend, the Rabbits acquired their unusual name during a fight between different factions in their original gang: the Roach Guard. At one point, someone threw a dead bunny into the room. Since “dead rabbit” was slang for someone who started fights, the breakaway faction decided to use that as their new name. The Dead Rabbits eventually became aligned with the incredibly corrupt Tammany Hall organization and could often be seen at polling stations running off anyone who wasn’t going to vote their way. In 1857, they were key players in the huge Fourth of July riots. Just what happened in the chaotic gang war isn’t well documented, with estimates of the death toll ranging from 8 to 100. An estimated 5,000 gang members took part in the Fourth of July riots, which raged for days. The Dead Rabbits were also at the forefront of the even worse 1863 Draft Riots. In that case, the carnage was only stopped when the mob was subdued by federal troops. By then, the death toll was enormous, and countless homes and buildings—including an orphanage—had been burned to the ground.

3Rocks Push

In the 1870s, gangs known as “pushes” divided the streets of Sydney, Australia. One of the largest was the Protestant group known as the Rocks Push, which operated in opposition to the city’s Catholic gangs. Most of their crimes involved theft and harassing the local dockworkers. In addition to the core male members of the group, the women associated with the gang were right in the thick of things, often acting as decoys. Of course, there was the usual fighting, especially with Sydney’s Catholic “larrikins.” Eventually, the rivalry would be resolved in an unusual way. In 1871, Larry Foley, one of the leaders of a Catholic gang, challenged the head of the Rocks Push to a fight. Unbeknownst to the Rocks Push, Foley had been training under “Perry the Black,” a Canadian boxer who had been at the top of his sport before being transported Down Under as a punishment for passing forged banknotes. The fight that ensued became the stuff of legend—it’s said that the two gang leaders went 71 rounds before police finally stepped in. Recognizing that he was beaten, the leader of the Rocks Push handed control of the gang over to Foley. Gradually, Rocks Push went the way of other street gangs and fell apart. Foley briefly tried to get the gang off of the criminal path, but failed. Over the next 20 years, there were a rash of gang-related rapes and murders (perpetrated, in large part, by other groups), which forced law enforcement to crack down. But the Push name did briefly come back into fashion in the 1950s, when it was adopted by a group of writers, artists, and filmmakers, who defied the conservative establishment by embracing gambling, horse racing, and public art.

2Glasgow’s Penny Mobs

Glasgow has always had a reputation as a tough town, and things were no different in the late 1800s. For the last few decades of the century, the city was the stomping ground of the “penny mobs“—gangs who staked out their territory and would rob anyone they thought a fitting target. The term “penny mob” was coined by the media and given to the street gangs for a number of reasons. Firstly, rather than serving time in jail, crime was so widespread that those found in midst of gang activity were often fined a single penny, then sent on their way. It was also said that the gangs would beat and rob someone for nothing more than a penny. They also had some pretty striking similarities with the street gangs that were running New York City at the time—notably, the Irish were right in the middle of it all. Glasgow was largely Protestant, but it was also home to a large Irish immigrant population escaping the famine and poverty of their homeland. Many of Glasgow’s gangs were formed in the years around this immigration, and much of the violence started against Irish immigrants. Even non-Catholic Irish immigrants were still very much on the other side of the divide from the natives of Glasgow. Violence for money soon became violence in the name of religion, and there are few topics more heated than that.

1The Mandelbaum Gang

Frederika Mandelbaum was better known as Marm, and a mother is exactly what she was. She set up shop in New York City sometime around 1864, and for 20 years she built up a reputable gang of thieves, pickpockets, and bandits—who all trusted her to pay them fairly for what they stole. It’s estimated that she and her gang handled merchandise that would today be worth somewhere around $200 million. Part of Mandelbaum’s success was due to the way she treated her network of thieves. She stood by her own, and always kept a law firm on retainer for any of her gang who got caught. She was famous for handing out bribes to police and judges, encouraging them to look the other way. Unlike most of the other street gangs, a large number of Mandelbaum’s crew were women. Mandelbaum herself thought highly of women who wanted to do something other than housework and even opened a school to train the next generation of female thieves and pickpockets. In addition to the school, she also owned a network of warehouses that she used to hold her stolen merchandise, and a three-story building where she ran a haberdashery and held dinner parties for the upper crust of New York society. Her apartments were furnished, in large part, with merchandise stolen by her gang, and it’s uncertain whether or not any of her guests ever spotted their missing cutlery there. Read More: Twitter