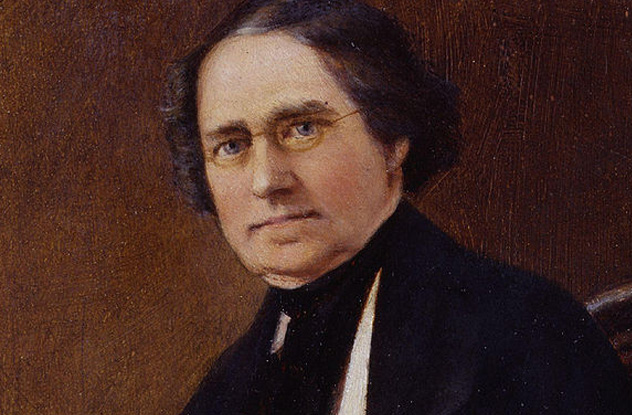

10Dionysius Lardner’s Railway Error

Dionysius Lardner was a 19th-century Irish professor, mathematician, and popularizer of science. He was a staunch supporter of Charles Babbage and would often give talks on the difference engine, an early calculator. Lardner also wrote several mathematical papers, but his crowning achievement was the Cabinet Cyclopedia. The 133-volume series presented topics like science and history to the average reader. It featured contributions from numerous learned figures of the day such as John Herschel, Mary Shelley, Walter Scott, and Thomas Moore. Despite all of his success, Lardner’s career was not without its hiccups. He made several predictions regarding technology that were ludicrous enough to earn him derision from his fellow scientists. Lardner once concluded that using steamships to cross the Atlantic Ocean was completely infeasible, akin to a “voyage to the Moon.” However, his most noteworthy blunder was his take on railway travel. Despite Lardner’s scientific background, a medical doctor he was not. This is evidenced by his professional take on the matter: “Rail travel at high speed is not possible because passengers, unable to breathe, would die of asphyxia.”

9Finnur Magnusson’s Runes

Although the name probably isn’t very well known nowadays, Finnur Magnusson was a prolific Icelandic archaeologist of the 19th century. He had a great passion for Norse history and mythology, particularly for runes. Magnusson was often brought in to analyze and translate potential runes, and he became the first to claim to have deciphered part of the runes on the Runamo. Runamo is a dolerite dike in Sweden that supposedly bears runic inscriptions. According to Magnusson, the part he translated was a skaldic verse talking about the battle between the Danish king Harold Hildetand and the Swedish king Sigurd Hring. Magnusson was not the first to discover the runes at Runamo. As early as the 12th century, the runes had been declared to be too worn down to be legible anymore. So Magnusson caused quite a stir when he claimed to have discerned an entire poem within the dike. Unfortunately for him, some geologists came to check the inscriptions, and in 1844, they concluded that the ancient runes were actually just natural cracks in the rock.

8Christopher Columbus’s Mermaids

It’s not uncommon for your eyes to play tricks on you after a long time at sea. Even the most experienced sailors can be fooled, given the right circumstances. Take Christopher Columbus, for example. In 1493, while sailing near the Dominican Republic, Columbus thought he saw three mermaids. He didn’t, obviously, but mermaid sightings were quite common among sailors of that era. Nowadays, it is generally considered that Columbus actually saw manatees that, despite weighing up to 600 kilograms (1,300 lb), could probably be mistaken for a human from a very long distance. Other possible culprits included the dugong and the now-extinct Steller’s sea cow, which was a common sight back then. It’s probably just as well that Columbus didn’t see mermaids, though. According to him, they looked nothing like how they were depicted in paintings. Columbus claimed that the mermaids’ beauty had clearly been exaggerated since their faces looked very manly. Oddly enough, Columbus’s notion that mermaids aren’t as enchanting as we think was backed up by other prominent explorers such as Henry Hudson and Captain John Smith, who also reported seeing unsatisfying mermaids.

7Richard Nixon’s Fashion Faux Pas

It didn’t take long for Nixon to commit his first blunder as president of the United States. He wasn’t very happy with the White House police uniforms. Nixon thought it made his men look “slovenly,” so he commissioned a new version. This one would be inspired by various traditional European uniforms that Nixon admired, such as the guards at Buckingham Palace. And what better occasion to unveil this new look than a visit from the British prime minister Harold Wilson? What he saw when he arrived were police officers dressed in double-breasted white tunics, complete with gold piping, starred epaulets, and some silly hats. It wasn’t long before the press got a hold of the story, and they were relentless. The Buffalo News said they looked like “old-time movie ushers.” Even Nixon supporters like Walter Trohan of the Chicago Tribune criticized the look, stating that the uniforms were too reminiscent of European monarchies to be suitable for a democratic nation. Most people simply thought they looked like marching band uniforms. Some modifications were attempted (like losing the silly hat), but after just two weeks, the whole thing was scrapped. In the end, the uniforms were put to good use by being donated—to a marching band, of course. The Southern Utah State College received the uniforms in almost mint condition and saved a cool $6,000 by not buying new ones. They even had to turn down an offer from rocker Alice Cooper, who wanted to buy some for his band.

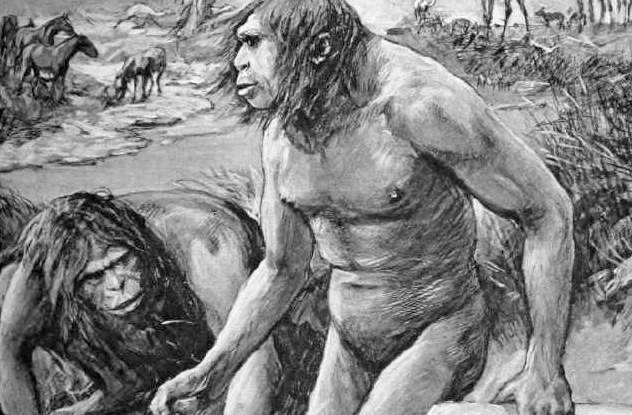

6Henry Fairfield Osborn’s Nebraska Man

Henry Fairfield Osborn is a big name in the world of paleontology, having served as president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years. However, a long and distinguished career such as his cannot be without its blemishes, and Nebraska Man was definitely his biggest. Like Piltdown Man, Nebraska Man was touted as a new species of anthropoid primate and would turn out to be just as fake. Perhaps in a moment of hubris, Osborn proclaimed the existence of the species from just a single tooth he received in 1922 from an amateur Nebraska geologist named Harold Cook. The new species was named Hesperopithecus haroldcookii in honor of its discoverer, although Osborn jokingly suggested that it was named Bryopithecus to “honor” the “most distinguished primate” ever produced by the state of Nebraska. He was referring to rival William Jennings Bryan, the prominent anti-evolution activist, who would act as a lawyer in the Scopes Trial just a few years later. Pride comes before a fall, as Osborn was about to find out. His description of Nebraska Man didn’t satisfy the scientific community, and more digging was done on Harold Cook’s ranch. After a few years, more bones belonging to the species were found. As it turned out, Hesperopithecus haroldcookii was not one of our ancient ancestors. It wasn’t even a primate. The tooth belonged to an extinct species of peccary, an animal similar to the domestic pig.

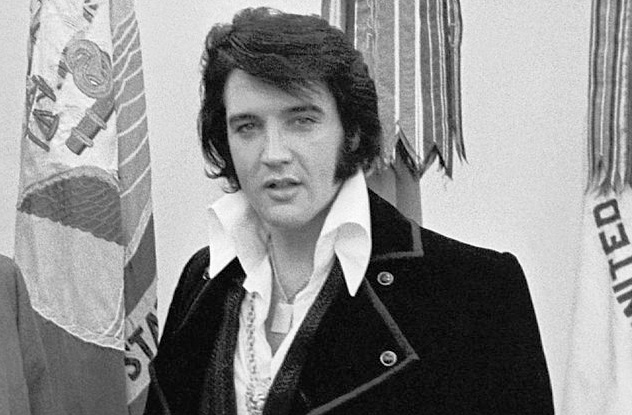

5Elvis Presley’s Catfish

Elvis Presley’s life is a well-documented story of the rise and downfall of one of music’s most prominent figures. He soared to unparalleled heights, but the last years of his career were marked by increasingly erratic behavior and sloppy shows from a bloated performer. One of Elvis’s low points was a remark during a 1975 Norfolk concert that made several of his backup singers leave the stage in disgust. The event became known as the “catfish incident.” While on stage, Elvis said that he smelled green peppers and onions, which probably meant that the Sweet Inspirations had been eating catfish. The Sweet Inspirations, his gospel backup, were all black women, so the remark was immediately perceived as racist. Elvis continued his taunts until two of the Sweets, along with backup soprano Kathy Westmoreland, left the stage. As it turned out, Westmoreland and Elvis had had a fling. Post-breakup, Presley directed sexual references at her while onstage. This time, he’d switched it up and picked on the Sweet Inspirations because he “thought it was funny.” Elvis apologized to the singers, and the Sweets returned for next night’s show.

4Johannes Stoffler’s Apocalypse

History has had more than its fair share of doomsayers warning us about the end of the world. Some of these apocalypses were the result of prophetic visions, others came from religious texts, and some had a pseudoscientific explanation behind them. Regardless of their nature, all doomsday predictions had one thing in common—they were all wrong. One such prediction came from someone who really should have known better: the German priest-turned-professor Johannes Stoffler. This one blemish taints an otherwise impressive career. Stoffler was a mathematician and astronomer whose works were widely circulated throughout 16th-century Europe, particularly a book on how to build and use an astrolabe. He even has a crater named after him on the Moon. Unfortunately, Stoffler’s calculations in 1499 led him to believe that a giant flood would engulf the whole world 25 years later—specifically, on February 20, 1524. His reputation lent credence to the prediction, and over 100 pamphlets were published throughout Europe warning everyone of the impending doom. One German nobleman named Count von Iggleheim even commissioned a giant ark for himself and his family. When the fateful day arrived, scores of people gathered around von Iggleheim’s ark on the Rhine out of curiosity. In an extreme case of bad timing, a light shower started pouring, enough to incite a panic. Over 100 people died in the stampede, and von Iggleheim was stoned to death when he refused to let anyone inside the ark.

3William Henry Preece’s Telephone Prediction

Sir William Henry Preece was a Welsh inventor and engineer who worked on the first national communication systems for Great Britain using telegraph and telephone technology. He also served as president for the Institution of Civil Engineers and Institution of Electrical Engineers and retired as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. Despite his success in this area, Preece was not always convinced about the potential of the telephone. In fact, his early remarks regarding this new invention still get mentioned today as one of the worst technological predictions in history—“The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys.” Despite Britain’s plentiful supply of “messenger boys,” it’s pretty clear today that Preece severely underestimated the usefulness of the telephone. His beliefs were probably the result of decades of working as an engineer for the General Post Office, time during which Preece contributed several inventions and improvements to the telegraph system. To his credit, Preece eventually realized his blunder. He quickly changed his tune and became a supporter of the telephone, even becoming one of the first to introduce the invention to Great Britain.

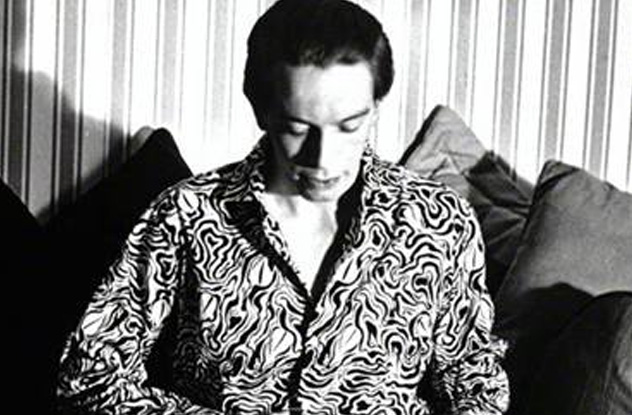

2Kenneth Tynan’s Blind Blunder

A successful writer and an even more successful critic, Kenneth Tynan assured his place in the history books in 1965 when he supposedly became the first person to say the word “f—k” on television. Of course, this caused a huge hullabaloo. The BBC issued a formal apology, and the House of Commons passed four separate motions signed by 133 MPs from both parties to combat immorality and filth on TV. Some called the moment a genius move of self-publicity. A frequently overlooked faux pas of Tynan’s took place much earlier, when he was reviewing singer Frank Ifield’s debut at the Palladium. Tynan couldn’t help himself from bursting into cheers, gasps, and applause at odd moments during the performance. Afterward, Tynan gave Ifield a glowing review, praising his courage and gallantry at overcoming his handicap. This must have left many people confused, Ifield in particular. What handicap was Tynan talking about? Tynan thought Frank Ifield was blind. He wasn’t. Tynan had mistaken Ifield for a blind singer with a similar name. So, when Tynan was giving out random gestures of approval during the performance, he was marveling at how gracefully Ifield was strolling around on the stage without fear. It was almost as if he could see where he was going.

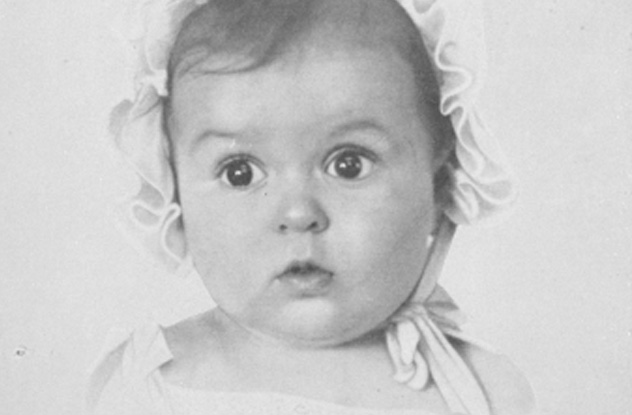

1Joseph Goebbels’s Nazi Poster Child

A lot of the credit for the Nazis’ initial success goes to Joseph Goebbels, the man in charge of the propaganda machine that twisted an entire nation. His relentless efforts to paint the Jewish people as responsible for all the world’s evil ensured that the Nazi party had enough support to take power. In 1934, long before World War II, Goebbels was already working on planting the seeds of hatred. He was looking for the perfect poster child. If Hitler represented the current face of Nazism, this child would show everyone the future. To do this, Goebbels hosted a contest to find the most beautiful Aryan baby. The winner was a two-month-old girl whose now-iconic face was used in all kinds of Nazi propaganda. Goebbels made just one tiny mistake—the girl was Hessy Levinsons Taft, and she was Jewish. Obviously, Goebbels had no idea of this when he personally picked Hessy as the most beautiful Aryan baby in the world. In fact, her Jewish parents were quite shocked when they saw their infant daughter in a Nazi magazine. The photographer who took the original photo had been ordered to send in his 10 best pictures and included Hessy as a joke at the Nazis’ expense. Follow Radu on Twitter.