While ASL may be the most well-known of the non-spoken languages, the reality is that it is just one of hundreds (or perhaps thousands) of varied sign languages that have cropped around the world. In fact, think of any way to communicate or make noise without speaking, and there is probably a language somewhere on our diverse and fascinating globe that uses it—be it humming, drumming, whistling, or tapping.

10 Silbo Gomero

For centuries, one sound has been a constant presence down the narrow volcanic ridges and valleys of the island of La Gomera—whistling. That’s because the 22,000 people who live here are unique in the Canary Islands archipelago, bilingual in Spanish and Silbo Gomero, a whistled version of the Spanish language that has allowed locals to communicate with each other from distances of over 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) away since the 16th century.[1] Using the natural formations of the small, circular volcanic island, the whistled language of 4,000 words echoes up and down La Gomera, creating a truly unique and somewhat ethereal atmosphere. Many on the island understand the language, and most of the older inhabitants are fluent, but with the looming threat of Silbo Gomero’s extinction over the past few years, the local government now requires that all children learn it in school, helping to revitalize the language and keep the island whistling.

9 Sfyria

If Silbo Gomero impressed you, prepare to be astonished by the whistled language of Sfyria. A nearly extinct 2,500-year-old language known by only six people in the world, Sfyria sounds like birds singing and is a true linguistic feast.[2] And unlike Silbo Gomero, Sfyria has a completely unique vocabulary and grammar and is not a whistled version of another, already spoken language. The incredibly rare Sfyria heralds from a tiny mountainous village called Antia on the little-known Greek island of Evia and may have been invented as a way to warn residents about invading pirates. Its remote location has allowed the language to survive, only being discovered as late as 1969, when a plane crashed near Antia, and rescuers on the scene heard locals using the whistling to communicate. But its remote location is now, sadly, part of its demise. The village’s population has been falling for decades, and now, the number is down to just a few dozen, with only six Sfyria “speakers” left.

8 Monastic Sign Language

So, imagine you are a monk sitting in your monastery, completely devoted to God through ritual prayer and a dedicated vow of silence. Others surround you in silence, but naturally, you want to converse. You know you are not allowed to talk, but nowhere does it say you cannot communicate. It was that exact thought process in the tenth century by Christian monks that helped create Monastic sign language, a way that monks began to communicate with their fellows through gestures and hand movements yet at the same time continuing to respect their vow of silence to God.[3] While the lexicon is limited and mainly revolves around the day-to-day activities of the monastery, many different versions of Monastic sign language have cropped up in monasteries around the world over the past 1,000 years, some of which continue to be used today.

7 The Tapping POWs

It’s not just monks who have to be silent; some people, like prisoners, are forced to be. American prisoners of war (POWs) during the Vietnam War had an ingenious way of talking to each other in Vietnamese prisons—they used tapping.[4] Banned from talking with each other, the POWs created a system of taps, similar to Morse code, where they would tap out letters to form words and sentences. While the tapping could be used for simple things like “hello” and “good night,” it was also used in complex sentences, such as telling others what interrogation had been like and therefore warning them of what to expect when it was their turn. Can this tapping truly be classified as a language, though? Well, former POW Vice Admiral James Stockdale’s words seem convincing. “Our tapping ceased to be just an exchange of letters and words; it became conversation,” he wrote in his memoir. “Elation, sadness, humor, sarcasm, excitement, depression—all came through.”

6 Khoisan Clicks

A form of communication that has fascinated visiting foreigners to many African nations for years has been the use of “clicks.” Khoisan, a group of languages from across the African continent, has used clicks for consonants for generations, and while many of these languages are now extinct, there are several that continue to be used in places like the Kalahari Desert and Tanzania.[5] In fact, Dutch colonialists in South Africa were so stumped by the clicking noises of Khoisan speakers that they actually nicknamed them “stutterers,” believing the noises were a form of stuttering speech problem, rather than a language. Despite being grouped together, the Khoisan languages are actually very diverse, and many can be significantly different from each other—the clicks may sound similar to foreign ears, but they are definitely not!

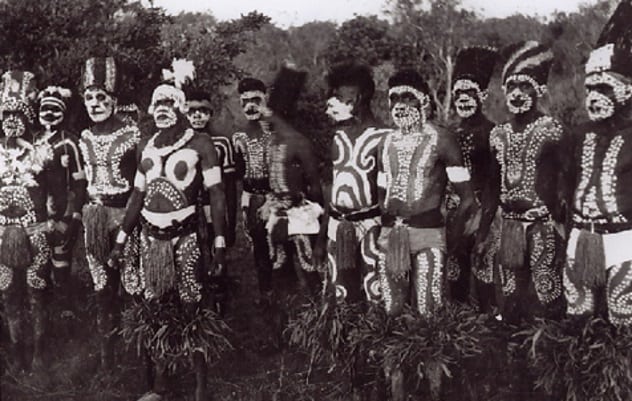

5 Damin

The Damin language—meaning “being silent”—is a now-extinct nasal clicking language from Australia, the only clicking language known to have been fostered outside of Africa. Created by the Lardil people, an indigenous group from the Northern Australian island of Mornington, this clicking language was being “spoken” up until the 1970s in male initiation ceremonies, where it was taught to young males as part of their rite of passage to becoming men.[6] With around 150 root words, each word or noise would represent several words in the Lardil’s spoken Tankic language. While the Lardil believed that the language was created during a time when mythological ancestral figures roamed ancient Australia, the far more likely and far less dramatic explanation is that Damin was simply created by Lardil elders as part of the rite of passage for young men.

4 Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language

While the most well-known unspoken language in the world may be American Sign Language (ASL), there are actually hundreds, if not thousands, of different types of sign languages around the globe. Many of these have been created organically in small, mostly rural communities with exceptionally high rates of deafness. One of those communities, the al-Sayyid Bedouin tribe, can be found in the hot, dusty Negev Desert in Southern Israel. The community numbers around 3,000 people but has had an uncommonly high rate of deafness for decades due to a genetic disorder that came from the tribe’s founders in the 19th century. Currently, around 150 people, or five percent, of the tribe’s population is thought to be deaf; for comparison, the rate in the United States is just 0.1 percent. Because of this, a unique sign language began to form in the community during the mid-20th century and is regarded as the tribe’s second language. With everyone able to sign fluently, and therefore able to talk to all members of the community, the deaf of al-Sayyid are not stigmatized or left out of community business—in fact, marriage between deaf and non-deaf members is common.[7]

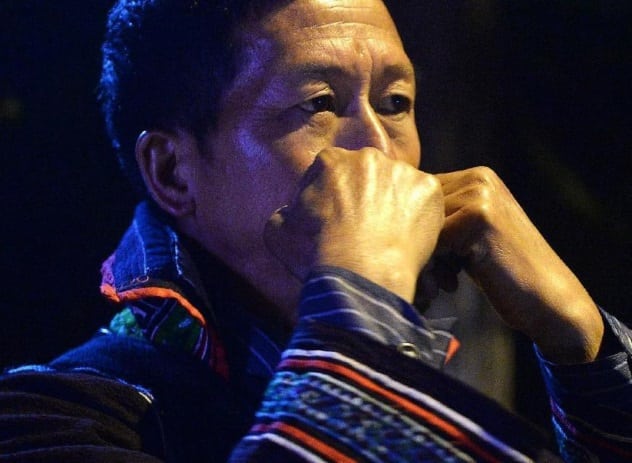

3 Hmong Whistle Language

If you ever find yourself in the foothills of the Himalayas among the Hmong people, then strain an ear and put it to the wind—you might be lucky enough to catch the sound of birds singing, or at least something that sounds very much like that . . . In fact, that singing may not be the sound of birds chattering among themselves but rather the whistled language of the Hmong, whose tuneful whistles carry whole sentences along the wind, passing them from person to person through valley and mountain for distances of up to 8 kilometers (5 mi). It’s also a very romantic language. “Boys wander through the nearby villages at nightfall,” the BBC reports,” whistling their favourite poems between the houses. If a girl responds, the couple then start a flirty dialogue.”[8]

2 Piraha

It is, technically, still a spoken language, however. But this is where things get especially interesting. Due to the very small number of consonants and vowels, but the very large and complex range of tones used, the Piraha often completely drop the consonants and vowels and just hum their sentences, getting rid of speech altogether.[9] It’s not just humming, either. The 800 people who “speak” the language sometimes choose to sing or whistle it instead.

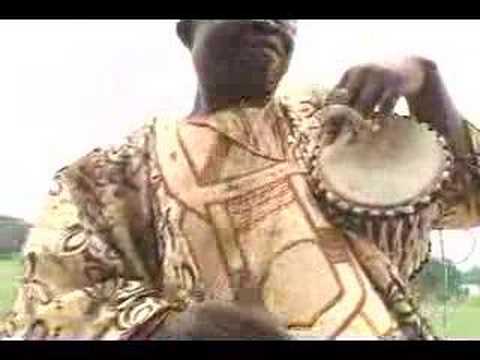

1 The Talking Drum

Some unspoken languages can also be lifesavers. Used in West Africa up to and including the present day, drumming has a centuries-long tradition in the region as a form of communication. It also had a role to play in the slave trade. Using what is called a “talking drum,” an hourglass-shaped drum that could copy the tone and accent of speech, villages and kidnapped locals were able to communicate over distance and with each other secretly despite the marauding slave traders—and this form of communication continued on slave plantations throughout the world.[10] For skilled players, whole sentences could be created on the drum using not just the drumhead but cords that run down its side that allow a user to control the pitch. While the talking drum can still be used to talk between friends, these days, it remains most alive in West African culture through music. I’m a professional journalist and writer of several years who travels extensively for work.