Today, thanks to the imaginations of inventors, amputees have more options than ever before for rehabilitation after such tragic injuries. Here is a list of the most interesting facts in the history of prosthetic technology, from ancient times to the speculations of a distant future.

10 The Egyptian Toe

A prosthesis’s purpose is to restore the function of the missing limb. So if you were to imagine early prostheses from history, most would imagine an arm or a leg. That’s why it’s so surprising that one of the earliest prosthetic artifacts was for something as innocuous as a toe. A wooden big toe, roughly 3,000 years old, belonged to a noblewoman in ancient Egypt.[1] But why a toe, of all things? If we are talking functionality, our toes are useful for things like balance and stability while we’re walking, and the big toe in particular bears 40 percent of the weight of each step we take. Also, a big toe would have been needed to properly wear traditional ancient Egyptian sandals. However, there is a second use for this type of prosthesis: the aesthetics and wholeness of the individual. We can’t know for sure, but the noblewoman who wore this prosthesis very possibly had it made to feel more at home in her body and gain a sense of normalcy among those around who were not missing the appendage. This sheds light on how prostheses are devices that aid in both the physical and emotional rehabilitation of their wearers.

9 General Marcus Sergius

Ancient Rome was a civilization known for its many battles and wars, so it stands to reason with all the fighting and maiming that the Romans would have made some contributions to the history of prostheses. General Marcus Sergius and his iron right hand are the stuff of legends. In his second year in the military, Sergius lost his right hand.[2] Whether he made the prosthesis himself is unclear, but eventually, after fighting several battles with only one hand, he acquired a prosthetic hand that was strapped to his arm. The prosthesis was made to hold his shield. The loss never slowed Sergius down. He escaped capture by the enemy twice and freed the cities of Carmona and Placentia from enemy hold. His courage and character show that disability only holds you down as much as you let it.

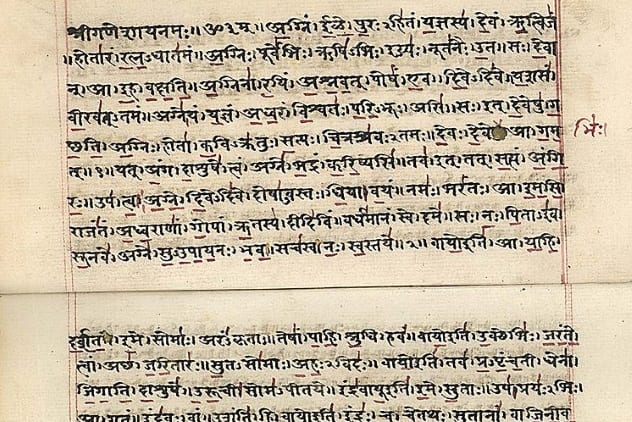

8 The Rigveda

The Egyptian toe may have been one of the earliest prostheses found, but the Rigveda is the earliest known document that mentions prostheses. Written between 3500 and 1800 BC in India, part of the document tells the story of the warrior queen Vispali (also spelled “Vispala”). Translated from Sanskrit, it says, “When in the time of night, in Khela’s battle, a leg (caritra) was severed like a wild bird’s pinion, Straight ye gave Vispali a leg of iron that she might move what time the conflict opened.”[3] The Vedas [Hindu for “Knowledge”] have been known to contain references to early practices that reflect how we practice medicine and surgery today. Although the iron leg is not described, it wouldn’t be unwise to suspect that its inclusion in the story references the use of prostheses at that time in history. As a side note, there is some debate on whether Vispali was a human or if she was, strangely enough, a horse. Most scholars assume she was not a horse, but there are a small fraction of people who prefer the horse mythology over the warrior queen. To each their own.

7 Ambroise Pare

Losing a limb used to be the sort of thing that happened only by some horrible accident (or in battle, of course). Ambroise Pare, a French barber-surgeon, was a pioneer in exploring amputation as a medical procedure, which he introduced in 1529. Pare perfected the surgical procedures to safely remove the limbs of injured soldiers. Pare also pioneered the use of wire or thread to constrict the patient’s blood vessels to keep them from bleeding out while in surgery. Saving some extra skin and muscle during surgery to cover the resulting stump was also one of Pare’s techniques, called “flap amputation.” Pare also developed designs for prosthetic hands and above-the-knee legs.[4] Pare kept a notebook with the designs for all of his prostheses. This included an amusing drawing of a prosthetic nose with a rather distinguished fake mustache.

6 The US Civil War

It should come as no surprise that the most progress in the development of prostheses came during times of war. It’s estimated that around 30,000 people needed to undergo amputations due to battle injuries during the US Civil War. (Some put the number at 50,000.) With the rise in demand for quality prostheses, a Confederate soldier named James Hanger created the “Hanger Limb.” Hanger became the first Confederate amputee when his left leg was struck by a Union cannonball in the first battle of the Civil War. His leg had to be amputated above the knee, and he was given a wooden leg that he soon found to be inefficient. The Hanger Limb had hinged joints made from metal and barrel staves that made it the most advanced prosthesis of its time. Hanger soon founded a company to distribute his invention.[5]

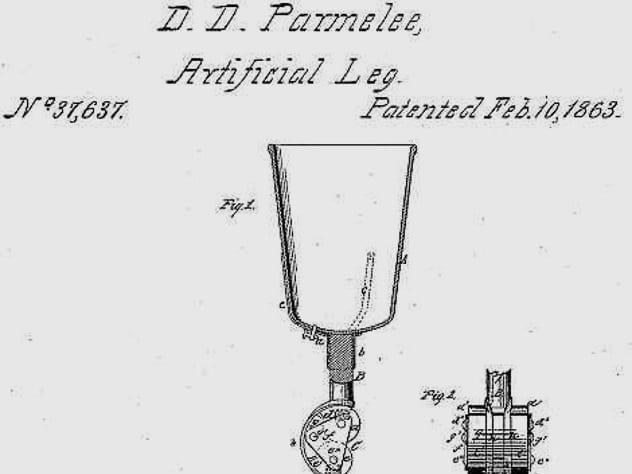

5 Dubois D. Parmelee

Around the same time as James Hanger’s prostheses were first designed, there was another inventor making efforts to improve prosthetic technology. Dubois D. Parmelee, a chemist from New York City, was the holder of several patents having to do primarily with rubber. Parmelee’s contribution to prosthetic technology was focused on how the limb was attached to the body. Before Parmelee, prostheses had harnesses and straps that kept the limb in place. Unfortunately, the movement of the prosthesis could rub painfully against the amputee’s stump. Parmelee invented a suction socket that used atmospheric pressure.[6] Prostheses of this nature would have to be custom-made for each amputee to ensure that the shape and volume were perfect. The atmospheric pressure acted as a vacuum, which kept the prosthesis from aggravating the soft tissue of the amputee.

4 The Artificial Limb & Appliance Service

World War I brought more destruction with even more advanced machinery. With all the fighting on the front lines in the mud and bacteria, infection was widespread. With new veterans, some with several amputations, the costs for custom-made prostheses were sky high. During the war, the British government opened a “Limb Service” to deal with the wounded. This was the beginnings of the Artificial Limb & Appliance Service (ALAS) in Wales. This service would persist and evolve after the war and is still active today.[7] Britain wasn’t the only country to fund veteran and amputee services after the wars; such services would become widespread in many developed countries throughout the 20th century.

3 Ysidro M. Martinez

The Egyptian toe perfectly demonstrated the need for both form and function in the design for high-quality prostheses. However, prosthetic leg designers often were too focused on replicating the shape of the missing limb. Although the prosthesis would look good, walking with the new leg proved to be clunky and awkward. This all changed when Ysidro M. Marinez, an amputee and inventor in the 1970s, took a more abstract approach. His prostheses were lighter and had a higher center of mass and weight distribution, which reduced friction, balanced gait, and made it easier to speed up and slow down while walking.[8] His invention was only for below-the-knee amputees, but his prostheses proved that such devices could be both functional and stylish, even if they don’t perfectly replicate the appendages that were lost.

2 3-D Printing

We’ve explored the evolution of design, functionality, and purpose for prostheses, all of which have improved increasingly in modern times. Now, it’s time to consider production. As discussed previously, prosthetic limbs need to be custom-made for each amputee so that they’re comfortable and secure while in use. The advances in 3-D printing technology have improved efficiency, and for engineers and physicians, they’ve cut down on the time spent making these prostheses. The prostheses are customizable, and as 3-D printing becomes more commonplace, these devices can be printed by anyone at any time.[9] 3-D printing can even create lightweight covers that create a more human silhouette. The covers give the wearer control over how these prostheses express their sense of self.

1 Smart Prostheses

Finally, there is the concept of intelligent prostheses. While the prosthetic limb designs we’ve previously seen are impressive, they still cannot replace the connection that an arm, leg, hand, or foot had to the amputee’s brain. An old-fashioned prosthetic hand may look like a hand and fit the limb it’s attached to, but it still may not be able to grasp and handle objects like the wearer may need it to. That all may change with the development of smart prostheses. Developers are finding ways to connect the brain to artificial intelligence in the prosthesis. So when the amputee thinks of picking up a cup, the prosthesis will move to their will. When the brain sees these new limbs as a part of the body, it will send signals to the remaining muscles. Developers hope to teach the prostheses to react to the contractions of the amputee’s muscles and then respond appropriately.[10] Beyond that, some developers are also designing their prostheses to monitor the person using them. The artificial limbs would monitor their movements and their health to warn them of infection or damage to the prosthesis earlier than the person would have noticed otherwise. Many of these advancements are still in their prototype phase, but as technology becomes more advanced and independent, it’s only a matter of time until smart prostheses become the norm. Savannah O. Skinner is a writer and fiction author from Canada, often under the pen name S.O. Skinner.