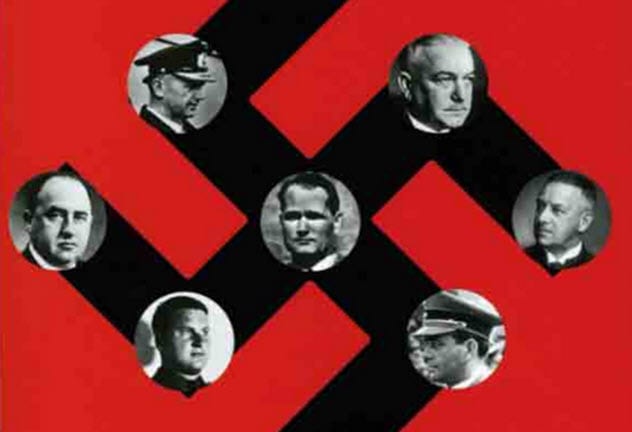

Seven of the officials—including Adolf Hitler’s successor, Karl Donitz—were sentenced to imprisonment in Spandau Prison in Berlin. Their story inside Spandau is largely forgotten, and the prison is now a shopping complex. But their years in Spandau are somewhat fascinating as the “Spandau Seven” were an eclectic mix of pure evil and genius.

10 Albert Speer Wrote A Memoir On Over 20,000 Sheets Of (Mostly) Toilet Paper

Albert Speer, the Minister for Armaments and War Production within Hitler’s government, was largely credited with keeping the huge German army working while they were under constant bombardment by the Allies. Speer’s genius was so highly regarded that the Allies spent time interrogating him prior to his arrest in 1945 as they were so interested in what they could learn from him. He was sentenced as a war criminal in the Nuremberg trials and spent 20 years in Spandau Prison. During the first 10 years, Speer wrote what would later become his two memoirs: Inside the Third Reich and Spandau: The Secret Diaries.[1] With the help of an orderly within the prison, Speer was able to get his handwritten notes—many of them on toilet paper—to his wife, who would send them on to his secretary and friend Rudolf Wolters. With his supporting group, Speer was able to smuggle out over 20,000 sheets of writing which would later be transcribed into his books. Wolters also had a bank account set up for this and other activities in support of Speer. Speer was released in 1966, a full 12 years after he was said to have completed his first draft of Inside the Third Reich in 1954.

9 Rudolf Hess Lived There Alone For Over 20 Years

Slowly over the course of the active prison years of Spandau, the Nazi criminals were released. It started with Konstantin von Neurath, who was released in 1954. A year later, Erich Raeder got out. Then, in 1956, Karl Donitz was freed from prison. Walther Funk was released in 1957, and Speer and Baldur von Schirach gained their freedom in 1966. This left Rudolf Hess as the sole prisoner of Spandau. The scrutiny of his time there has been widely written about. The prison was maintained for over 20 years with Hess as the sole prisoner. He had the run of the place and was given access to the gardens.[2] Hess’s mental state was well-known to be poor during his imprisonment as he was paranoid, suicidal, and unhinged. Despite this, the conditions for Hess improved over the years. He was later given a medical orderly, and a lift was installed for him as he began to age. He was asked questions about his disastrous attempt to fly to Scotland in 1941 and his relationship with Hitler. In 1987, Hess decided enough was enough. At age 93, he hanged himself by using an extension cord hung over a window latch.

8 The Prisoners Were Never On The Same Page

The imprisonment of the seven Nazis provided an interesting and candid insight into the mentality of Nazi officials, exposed because they were in such a confined space together. According to reports of prison life, Rudolf Hess was a loner who constantly complained of ailments and was generally mentally unstable. Hess was said to wail during the night in pain and would sometimes be given a placebo sedative just to get him to sleep. Albert Speer was liked by the guards, but he was generally a loner among his peers as they did not enjoy his meticulous nature. Former Grand Admirals Karl Donitz and Erich Raeder argued constantly with each other but stuck together against the other inmates.[3] Raeder was said to have been chief librarian of the prison with Donitz as his assistant. The other inmates nicknamed them “The Admiralty.” Donitz and Speer also hated each other, with the inscrutable Speer being set in his ways and Donitz maintaining that he (Donitz) was still head of state in Germany.

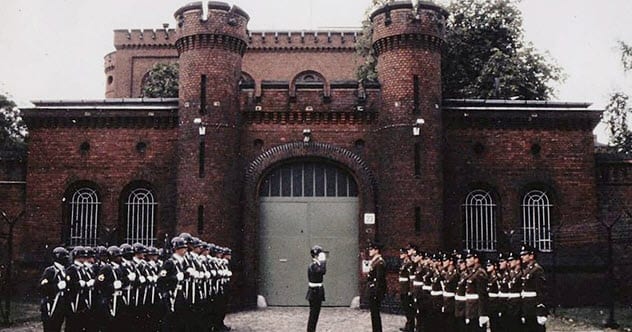

7 The Prison Was A Quadripartite Prison

One of the most unusual aspects of Spandau Prison was the agreement to separate the prison into four operations run by Britain, France, Russia, and the US. Each of the countries was responsible for the prison for three months of the year. The three months were not concurrent, so the different guards were constantly handing off to each other on a monthly basis. Brandon H. Grove, legal adviser to the US, described the changing of the guard as “an extraordinary sight,” particularly when the Americans handed things over to Russia.[4] One reason for this agreement was to give Russia a diplomatic presence in West Berlin at the time. It was the only place in West Berlin that Russian diplomats were exposed to Allied diplomats. Often, one of the countries would host the others at the prison. This became a “form of theater-noir” where the countries would try and out-host each other. During the different months of control, the prisoners would have food supplied by the relevant countries and the exterior guard was mounted by the controlling Allied or Russian military personnel.

6 The Prisoners Despised The Russian Months

The imprisoned Nazi officials often complained about the Russians during their control of the prison. It was said that the prisoners would gain weight during the American months and lose weight during the Russian months. The inmates also complained about the searchlights being too bright and keeping them awake at night.[5] In an eventually published letter, Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first postwar chancellor, pointed to the treatment by the Russians as the main source of deprivation and bad conditions. It was also noted that the Russians were the only party against the release of Rudolf Hess in his later years. He remained in the prison for over 20 years in isolation. Released letters also show that Moscow wanted Hess to “drink his retribution to the bottom of the cup” and that the Allies felt obliged to protect him from the Russians’ treatment. It seems that the only real option for all parties was for Hess to die, which would force an end to the quadripartite agreement. Once he did die, the Allies were quick to sever the relationship and have the prison destroyed.

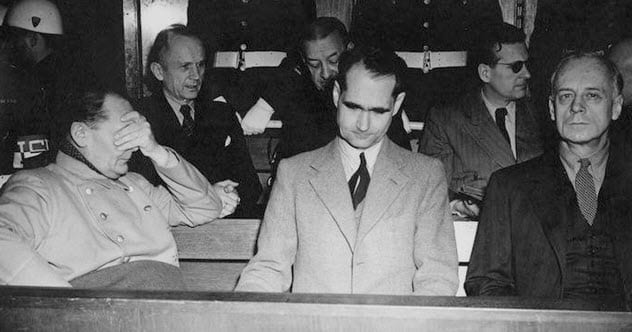

5 The ‘Impostor’ Theory

The popular “impostor theory” concerns Rudolf Hess, the most notorious prisoner at Spandau. Supposedly, even former US President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed in it. The British government commissioned four investigations into the theory. The conspiracy states that the man who served time in prison was not Hess at all. Instead, he was an impostor. The reasons given were that Hess appeared physically different from what he had looked like previously and that he had refused to permit family visits for over 20 years when in Spandau. Also, he appeared to have amnesia. Some theories put forward the notion that Hess may have been spared by the Allies from the Russians or that British operatives had murdered him when in captivity. Hess had been captured in Scotland in 1941 after crashing his plane on an apparent peace treaty attempt. The theory has been disproven in recent years after a thorough forensic analysis of a DNA sample taken from Hess while in Spandau was compared to a relative’s DNA sample. The samples matched by 99.9 percent, effectively ending the hysteria behind the impostor theory.[6]

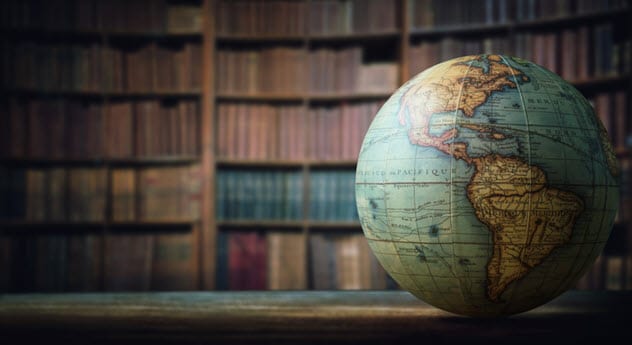

4 Albert Speer Traveled The World

Inside Spandau Prison, Albert Speer was known to take an active approach to his imprisonment. According to reports and his own memoirs, he had a rigorous regimen which included keeping physically and mentally fit, gardening, walking, and reading. Speer claimed to have read 5,000 books during his imprisonment, a figure which is considered exaggerated. He also took gardening very seriously and took over the other prisoners’ assigned plots when they lost interest in maintaining them. He would also allow himself “holiday” periods in which he would stop this self-imposed regimen. Supposedly, Speer made his daily walking more interesting by taking an imaginary trip around the globe using books as his guide. Speer would visually create the landscape in his mind and traverse the imagined surfaces. He even meticulously calculated these trips so that he would travel the accurate distances. He walked over 30,000 kilometers (18,600 mi). When his sentence was over, he was said to be near Guadalajara in Mexico. Speer was released in 1966 and later spent time in London.[7]

3 The Prison Was Demolished Immediately

After Rudolf Hess’s 21 years of isolation came to an end when he committed suicide in August 1987 at age 93, the decision was made to demolish the prison. There were fears that the facility would be turned into a neo-Nazi shrine, and the Allies were keen to sever the arrangement they had with Russia over the management of the prison. The idea was a shrewd one as Hess’s grave in Bavaria later became a shrine for neo-Nazis. It has since been moved after attracting rallies of up to 9,000 people. Spandau was demolished soon after Hess’s death, and all the materials of destruction were ground into powder. This powder was thrown in the North Sea or buried at the nearby RAF Gatow airbase. The only surviving piece of the prison is said to be a single set of keys which are housed in the UK.[8] In place of the prison, the site was developed as a shopping complex with a parking facility.

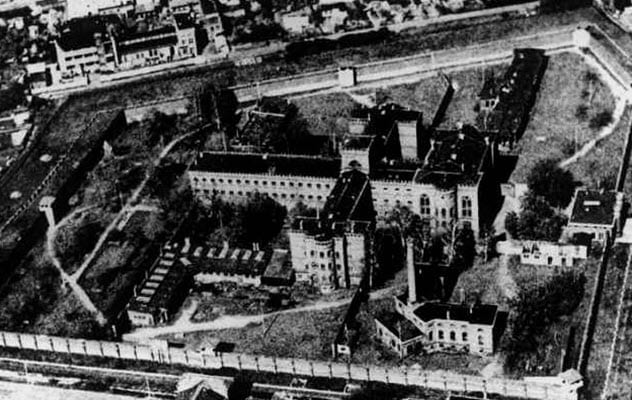

2 The Prison Was Severely Underutilized

Spandau Prison was built in 1876 as a detention center for the German military. At its peak, it held up to 600 inmates, contained hundreds of 3-meter (10 ft) by 2.7-meter (9 ft) cells, and included a prison chapel, library, canteen, and gardening facilities. After the Nuremberg trials, it was agreed that the entire prison would only hold the “Spandau Seven” Nazis. This meant that 60 soldiers, four prison directors and their deputies, medical officers, kitchen staff, and porters were all required to work in the prison for a total of seven prisoners. As the inmates were released during the 1950s and 1960s and Hess became the only prisoner, the level of this underutilization became absurd. Various initiatives were put forward to better use the prison as West Berlin was suffering from a lack of space in its own prison system.[9] The West Berlin government was also paying for the upkeep of the prison.

1 It Cost $800,000 A Year To Operate

Spandau Prison housed seven of the most senior Nazi officials to have survived the ending of the war, and the imprisonment of them was taken very seriously. The annual cost of $800,000 to run the prison was reportedly met by the West Berlin government. The prison was fully guarded at all times, and the inmates were by all accounts looked after better than standard prisoners would be. Although the regime was strict, the prisoners’ nutritional requirements were met year-round. Later, a $57,000 elevator was installed so that the elderly Rudolf Hess could get to his garden safely. The more research that happens into the Hess years, the more it sounds like he had an expensive retirement home at his leisure. The prison was one of a kind, and it is unlikely that we will ever see such measures again.[10] Hi. My name is Matt Garrow from Newcastle in the UK. I am interested in writing about history, geography, mysteries, disasters, tragic events, and anything that is generally interesting enough to catch my attention!