Forgers often go to extreme lengths to fool museums into buying their work. Some fakes are so good that historians and archaeologists have a hard time telling them apart from the real thing. Many museums have fallen victim to forgers, including the famous Louvre, which exhibited a fake artwork for several years without realizing it.

10 The Three Etruscan Warriors

In 1933, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (aka the Met) in New York City added three new pieces of art to its exhibition. They were the sculptures of three warriors from the ancient Etruscan civilization. The seller, an art dealer named Pietro Stettiner, claimed the sculptures were made in the fifth century BC. Italian archaeologists were the first to raise concerns that the statues could be forgeries. However, the museum curators refused to heed the warning because they believed they had gotten the artworks at a bargain and did not want to lose them to another museum. Other archaeologists later noted that the statues had unusual shapes and sizes for artworks created at their time. The body parts were also sculpted at unequal proportions, and the entire collection had little damage. The museum only discovered the truth in 1960, when archaeologist Joseph V. Noble recreated sample statues using the same techniques as the Etruscans and determined that the statues in the Met could not have been made by them. Investigations revealed that Stettiner was part of a larger group of forgers that had conspired to create the statues. The team copied the sculptures from collections held by several museums, including the Met itself. One of the warriors was copied from a picture of a Greek statue in a book from the Berlin Museum. The head of another warrior was copied from the drawing on a real Etruscan vase held by the Met. The sculptures also had unequal body parts because they were too big for the studio, forcing the forgers to reduce the size of some parts. One of the sculptures was also missing an arm because the forgers couldn’t decide on a pose for said arm.[1]

9 The Persian Mummy

In 2000, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan almost engaged in a diplomatic row over the mummy and coffin of an unidentified 2,600-year-old princess. The mummy, often referred to as the Persian Mummy, was discovered when Pakistani police officers raided a home in Kharan after receiving a tip-off that the owner was illegally trying to sell antiquities. The owner was Sardar Wali Reeki, who was trying to sell the mummy to an unidentified buyer for £35 million. Reeki claimed he had found the mummy and coffin after an earthquake. Iran soon claimed ownership of the mummy, considering that Reeki’s village was right at its border. The Taliban, who ruled Afghanistan at the time, later joined the fray to contest ownership of the mummy. The mummy was sent to Pakistan’s National Museum and put on display. However, several archaeologists discovered that several parts of the coffin were too modern. On top of that, there was no evidence that any of the tribes in Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan ever mummified their dead. Further analysis revealed that the mummy was actually the remains of a 21-year-old woman who may well have been a murder victim. It was sent to a morgue, and police arrested Reeki and his family.[2]

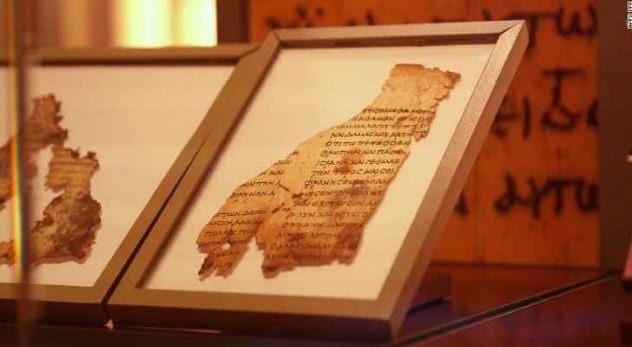

8 Dead Sea Scroll Fragments

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a group of handwritten scrolls containing Jewish religious text. They were written in the rough vicinity of 2,000 years ago and are among the oldest recorded writings of Hebrew biblical passages. Most of the scrolls and fragments are stored at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, while a few are in the hands of private collectors and museums. This includes the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, which had five fragments of the scrolls on display. However, that changed in 2018, when the fragments were revealed to be forgeries. The ruse was discovered after the museum sent the fragments to Germany for analysis. The museum sent the scrolls for examination after experts raised the alarm that they may have been fakes. These concerns were first raised months before the museum opened in November 2017. Speculators claim that the museum spent millions of dollars to acquire the fake scroll fragments. However, that remains unconfirmed, considering that the museum is not talking.[3]

7 Several Artworks At The Brooklyn Museum

In 1932, the Brooklyn Museum received 926 works of art from the estate of Colonel Michael Friedsam, who had died a year earlier. The artworks were a mix of paintings, jewelry, woodworks, and pottery from ancient Rome, the Chinese Qing dynasty, and the Renaissance. Colonel Friedsam gifted the museum the art on the condition that they received permission from his estate before selling or decommissioning any of it. That condition became a problem decades later, when the museum discovered that 229 of the artworks were forgeries. The Brooklyn Museum could not decommission the art because the last of Colonel Friedsam’s descendants died half a century ago. The museum cannot throw them away, either, because the Association of American Museums has strict rules guiding the storage and disposal of art by member museums. In 2010, the Brooklyn museum approached a court to allow it to decommission these forgeries. According to the petition submitted to the court, the museum would spend an initial $403,000 to furnish a warehouse to store the artifacts if the court refused its request. Then it would spend another $286,000 per year on rent and workers to care for the artworks.[4]

6 The Henlein Pocket Watch

Peter Henlein was a locksmith and inventor who lived in Germany between 1485 and 1542. We might not know him, but we all know and use his invention: the watch. Henlein invented the watch when he replaced the heavy weights used in clocks with a lighter mainspring, which allowed him make smaller clocks. Clocks were made by locksmiths and blacksmiths at the time. One of Henlein’s supposed early creations has been held at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Germany since 1897. The pocket watch resembles a small tin and fits in the palm of one’s hand. However, it became the center of a controversy soon after it was added to the museum’s collection. Several historians claimed the so-called Henlein watch was a forgery and not an original. This was even though the signature in the inside back cover of the watch proclaimed it to have been made by Peter Henlein in 1510. A 1930 report stated that the signature was added years after the watch was supposedly built. The experts reached their conclusion after determining that the signature went over—instead of under—the scratch marks inside the back cover. More recent tests revealed that most parts of the watch were manufactured in the 19th century, indicating it could be a forgery. However, other experts suggest the parts were made during an attempt to repair the watch.[5]

5 Almost Everything At San Francisco’s Mexican Museum

In 2012, the Mexican Museum in San Francisco achieved affiliate status with the Smithsonian Institution. The status allows the museum to borrow and loan artworks from over 200 partner museums and institutions with the affiliate status. However, the Smithsonian requires member museums to authenticate their collections before they can start loaning or borrowing artworks. In 2017, the Mexican Museum discovered that only 83 of the first 2,000 artworks it evaluated were authentic. This was troubling, considering that the museum has 16,000 artworks in its collection. Experts estimate that half of the museum’s inventory is fake. Some of the forgeries were deliberately created to be passed off as original, while others were originally intended as decorations. Some weren’t even linked to Mexican culture at all. The huge amount of forgeries is not surprising, considering that the museum received most of its collections from donors and hadn’t bothered to confirm their authenticity.[6]

4 The Amarna Princess

In 2003, the Bolton, Manchester, city council decided to acquire some new artworks for their local museum. They settled for a supposedly 3,300-year-old statue called the Amarma Princess, which depicts a relative of Pharaoh Tutankhamun of ancient Egypt. The sellers of the statue claimed it was excavated from an Egyptian site. This claim was backed by the British Museum, which found no signs of foul play after examining the statue. Satisfied, the Bolton city council paid £440,000 for the statue, which went on display at the museum. A few years later, the Bolton Museum discovered that the British Museum was wrong. The statue was a forgery, the handiwork of Shaun Greenhalgh, an infamous forger who made fake artworks which he sold to museums as originals. In a twist of irony, Greenhalgh lived in Bolton and had created the sculpture there. His parents, George and Olive Greenhalgh, acted as his salespeople and sold the forgeries to the museums. In 2007, Shaun was sentenced to four years and eight months in jail for his crime. His parents received suspended jail terms for their part.[7]

3 A Golden Crown At The Louvre

In the 1800s, two men contacted goldsmith Israel Rouchomovsky in today’s Odessa, Ukraine, to commission a Greek-styled gold crown as a gift for an archaeologist friend. In truth, the men had no archaeologist friend and only wanted to sell the crown as an original artwork from ancient Greece. Schapschelle Hochmann, the more cunning of the duo, claimed the crown was a gift from a Greek king to the king of Scythia sometime in the third century BC. Several British and Austrian museums turned down offers to purchase the crown. However, Hochmann found luck when the Louvre purchased it for 200,000 francs. Some archaeologists raised concerns that the crown could be fake soon after it went on exhibition at the Louvre. However, no one listened to them because they weren’t French. The Louvre considered their statements an act of jealously since they probably wanted the crown for their own museums. The archaeologists were proven right in 1903, when a man named Lifschitz, a friend who had seen Rouchomovsky make the crown, informed Rouchomovsky that his work was being exhibited as an original at the Louvre. Rouchomovsky traveled to France with a reproduction to prove he really made the crown. The revelation was bad news for the Louvre and good news for Rouchomovsky, who hit instant fame. A century later, the Israel Museum borrowed the crown from the Louvre and exhibited it as an original artwork of Rouchomovsky.[8]

2 Over Half Of The Paintings At Etienne Terrus Museum

The Etienne Terrus Museum is a little-known museum in Elne, France. It belongs to the city of Elne and exhibits the works of Etienne Terrus, a French artist who was born in Elne in 1857. In 2018, the museum added 80 new paintings to its collection. However, things quickly went south when an historian contracted to help arrange the new paintings discovered that around 60 percent of the entire museum’s collection were forgeries. The historian had no difficulty in determining the artworks to be fakes. His gloved hand wiped the signature off one painting in a single stroke. Several paintings also contained buildings that had not been built at the time Terrus was alive. Further analysis revealed that 82 of the 140 paintings held at the museum were forgeries.[9] The city council had purchased most of the paintings between 1990 and 2010. The forgeries were moved to the local police station while police opened an investigation.

1 Everything At The Museum Of Art Fakes

The Museum of Art Fakes is a real museum dedicated to art forgeries. Located in Vienna, Austria, the museum only collects fake artifacts and artworks. Parts of its collections includes pages from a diary supposedly owned by Adolf Hitler. In truth, the diary was forged by one Konrad Kujau. The museum categorizes its collections into forgeries intended to mimic the style of a more famous artist, forgeries intended to be sold as previously undiscovered artwork of a famous artist, and forgeries intended to be passed off as originals of already famous artworks. The museum includes a category for artworks it considers replicas. Replicas are made by artists after the death of the original artist. They were often labeled and sold as such, never having been claimed to be originals. The Museum of Art Fakes also dedicates some exhibition space to infamous forgers like Tom Keating, who created over 2,000 fake artworks during his lifetime. Keating deliberately made errors in his art so that they could be revealed as fake long after he had been paid. He called these deliberate errors “time-bombs.” The museum also exhibits the work of Edgar Mrugalla, who created over 3,500 fake pieces of art which he sold as originals. Mrugalla’s career as a forger ended after he received a two-year sentence for art forgery. He was only released on the condition that he take on a new career that required him to help authorities reveal fake artworks.[10]