Nevertheless, as incredible as it may seem, some of the most revered landmarks on the planet have been put up for sale. Several of them have actually been sold, a few more than once.

10 Carter’s Grove Plantation

Carter’s Grove Plantation occupies one of the most historic sites in the United States: a parcel of land near colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, overlooking the James River. It was privately owned for centuries before it was donated to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in the 1960s. The plantation proved expensive to maintain. The foundation closed it in 2007, and Carter’s Grove was sold to Halsey Minor, a wealthy Virginia businessman. When Minor experienced a financial reversal and declared bankruptcy in 2011, he put the property up for sale. Chicago businessman Samuel M. Mencoff purchased it for $7.5 million in 2014. The Georgian mansion suffered from neglect during the time Minor owned it. Plaster and brick were damaged by water leaks, and “simple maintenance work [was] left undone.” Through a spokesperson, Mencoff, a noted preservationist, said he’s proud to have assumed stewardship of the property and intends to preserve it as he works in association with Colonial Williamsburg to accomplish this goal.[1]

9 Hollywood Sign

By the late 1970s, the Hollywood sign erected on a ridge between Cahuenga Peak and Mount Lee in the 1920s to promote a real estate development was looking much the worse for wear. The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce wanted to replace it at a cost of roughly $250,000. To obtain the money, magazine publisher Hugh Hefner threw a lavish party at his Playboy mansion, selling the landmark letter by letter for $27,700 each. The fundraiser was a success, the old sign was removed, and “nine gleaming white letters were raised in its place.” All seemed well until 2002 when investors decided to develop 138 acres of land they’d bought near the sign. The land had belonged to billionaire Howard Hughes, who’d purchased it in 1940. He’d planned to build a home on it for his girlfriend, actress Ginger Rogers, but their relationship failed. When his land went on sale in 2002, the investors bought it. Now, if developed, the acreage might change the well-known landscape dramatically. A campaign, “Save the Peak,” was launched to buy the land and preserve the area near the fabled sign. Again, Hefner played a significant role in preserving the landmark’s location. With the purchasing deadline fast approaching, the fundraising campaign was $1 million short of the $12.5 million needed. Hefner donated the difference, and the Hollywood sign’s location was saved. “I am happy to have been in a position to have been able to do it,” Hefner said. “It is our Eiffel Tower. It represents, I think, more than a city; it represents Hollywood dreams.”[2]

8 Empire State Building

On May 29, 2013, the Empire State Building’s shareholders approved the public sale of the historic New York City skyscraper in a $4.2 billion IPO. Earlier, two groups had disagreed about the iconic building’s fate. One wanted a syndicate of 2,800 owners to retain ownership as they had since 1961. The other wanted to bundle the building with 18 other New York area properties into a real estate investment trust (REIT), selling shares in the properties to the public. REIT investors wouldn’t be able to claim depreciation of the properties, but they’d earn dividends on their shares of the investment.[3] Although there are now a number of taller structures, the 443-meter-tall (1,454 ft), 102-story Empire State Building was once the world’s tallest skyscraper. It retained first place as the tallest building in New York City until 1973 when the World Trade Center (WTC) was constructed. With the WTC’s destruction in the terrorist attacks of September 2001, the Empire State Building reclaimed its title as the city’s tallest skyscraper. However, it lost this distinction again to the 540-meter-tall (1,776 ft) Ground Zero building constructed on the former WTC site.

7 Alamo

The Alamo started out as the Mission San Francisco de Solano, built near the Rio Grande River in 1700. The location changed several times until it was finally established in San Antonio, Texas. By the end of the century, the mission was “secularized” and divided among local residents, Spanish and Native American alike. Soon afterward, the mission became a military garrison. During the Texas Revolution (1835–36), Mexican General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s army laid siege to the Alamo. They defeated its defenders, including Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie, in a bloody 90-minute battle after Santa Anna’s troops breached the walls of the fortress. When the soldiers departed in 1877, the Alamo’s grounds and compound were divided and sold to various buyers over a period of years. The property was modified, sometimes substantially, according to its owners’ purposes. In 1883, Texas bought the Alamo, except for the convento, or Long Barrack, whose owner decided to sell it to make room for the construction of a new hotel in 1903. San Antonio schoolteacher and preservationist Adina de Zavala raised $75,000 from “the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), a heritage group dedicated to honoring the men and battlefields of the 1836 revolution,” and the convento was purchased. The Texas legislature reimbursed the DRT two years later.[4]

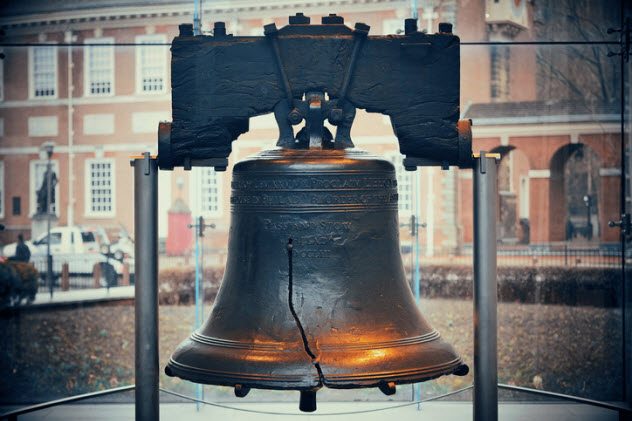

6 Liberty Bell

The replica of the Liberty Bell hanging in The Liberty Bell Center in Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has symbolized American freedom since July 4, 1776, when it rang to announce the reading of the Declaration of Independence. The original bell was recast twice, once in 1753 after it cracked when it was tested in London and then again to produce a better sound. Seventy years after it was recast the second time, it was almost sold as scrap metal. It was saved from the scrap heap only because it would have cost more to lower “the one-ton behemoth from its four-story perch in Independence Hall” than the $400 city officials wanted for the bell. “It’s pretty much a miracle that the thing still exists,” said Gary B. Nash, UCLA professor emeritus of history.[5]

5 Monticello

Although Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) was never formally trained as an architect, he studied many books on the subject. Rather than selecting “a stock design” and hiring a contractor to supervise construction of a house he planned to build on land he had inherited, Jefferson undertook the design and supervisory roles himself in 1768. After serving as ambassador to France following the death of his wife, Martha, in 1782, Jefferson returned to Virginia to create a new Monticello. He doubled the size of the original house and added fruits and vines to its already extensive gardens. His lavish spending left his daughter, Martha Randolph, with huge debts, and she had to sell the estate. In 1836, Uriah Levy, a real estate speculator, bought Monticello. He and his nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy restored and preserved the property. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, a nonprofit organization, purchased Monticello in 1923, and the site is now operated as a museum and educational institution.[6]

4 Bran Castle

In 2007, Romania’s former royal family put Bran Castle up for sale. The fortification is a famous landmark located on a cliff near Brasov. It was a defense against the Ottoman Turks and is associated with Vlad the Impaler, upon whom Bram Stoker based his literary character Count Dracula. The imposing edifice was the royals’ home from 1920 to 1948. Then the communist government confiscated it from Princess Ileana. After its restoration in the late 1980s, it became known as “Dracula’s Castle” and has been a tourist draw ever since. In 2006, the property was returned to Princess Ileana’s son, Archduke Dominic Habsburg, then 69. It’s now a museum because local authorities passed on his proposal to sell the castle for $80 million. After the sale was rejected, Habsburg again put the castle up for sale. His representative predicted that Habsburg would receive an offer of $135 million for the property. So far, there haven’t been any buyers.[7]

3 London Bridge

In 1968, industrialist Robert McCulloch was eager to attract tourists to Lake Havasu City, Arizona, then a steamy backwater. So he bought the fabled London Bridge, transporting the famous 19th-century landmark stone by stone across the Atlantic Ocean and the continental United States to reconstruct it over the Colorado River. In the 1960s, English officials had discovered that London Bridge was falling down, sinking 2.5 centimeters (1 in) every eight years. Renovations were considered too costly, so the 305-meter (1,000 ft) granite bridge was discarded in favor of constructing a replacement. Before the bridge was junked, City Councilor Ivan Luckin suggested the city try to sell it. Perhaps an American would take it off their hands. McCulloch offered officials twice the $1.2 million it would cost them to dismantle the bridge, adding $60,000 to “sweeten” the offer. The bridge was his. Each stone block was marked according to its span, row, and position. The disassembled bridge was packed and shipped to Long Beach, California, and a caravan of trucks took the blocks to their final destination. There, they were reassembled and the core of the structure was strengthened with steel-reinforced concrete. The disassembly, shipping, and reassembly cost McCulloch another $7 million, but London Bridge proved just the tourist attraction he’d needed. Lake Havasu City’s population “blossomed” after the landmark’s installation.[8]

2 New Scotland Yard

New Scotland Yard, the home of London’s celebrated Metropolitan Police Service (the Met) and one of the city’s most famous landmarks, was sold to an Abu Dhabi investor in 2014 for £370 million ($580 million), £120 million more than expected. The buyer planned to convert the police headquarters into luxury apartments.[9] As a result of the sale, artifacts once kept in a private “Black Museum” will now be moved to a public museum. Included among the items are “the ricin-filled pellet fired from an umbrella to kill Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov on a London bridge in 1978 [and] cooking pots used by a serial killer to boil up his victims.” The Met’s new headquarters will occupy a neoclassical edifice on the River Thames near parliament.

1 Stonehenge

In September 1915, the British magazine Country Life ran an advertisement: Stonehenge was for sale as a “companion feature” for a 6,400-acre piece of real estate. From the Middle Ages to the early 1800s, the land on which the Stonehenge monoliths stand was privately owned by the Antrobus family of Cheshire, who’d bought it in 1824. Before then, it had been claimed by a variety of owners. During World War I, the Antrobus family’s sole heir was killed in France and the property was put up for sale. There were no offers for the whole, which “included a mansion, farmhouse, and accompanying gardens,” so the land was divided into 89 lots, each of which was auctioned separately. Lot 15 contained the Stonehenge obelisks. Although the landmark was well-known, few expressed interest in buying it. Lot 15 sold for a mere £6,600 pounds, or about $8,700, which was far less than the expected sales price. The buyer, Cecil Chubb, gave it to his wife, who was unimpressed by the chipped and toppled stones which were then in a “decrepit” state. In October 1918, the couple deeded their purchase to the United Kingdom, and Chubb was made an honorary knight. “[Stonehenge is now] under the guardianship of English Heritage and is safe forever,” said curator Heather Sebire.[10] Leigh Paul enjoys reading and writing, but she’s not as crazy about arithmetic.