10 The Rhino Cave Ritual

A cave in Botswana has yielded intriguing artifacts that could have been used in the world’s oldest ritual. First examined in the 1990s, Rhino Cave produced over 100 spearheads in bright colors. Also inside was a python carved from rock. The stone reptile measures 6 meters (20 ft) by 2 meters (6.5 ft) and rests on a crushed wall. Some of the cracks in the cavern were stuffed with quartz chips. The site clearly held great importance for the San people who used it. The weapon points were delivered, often from a great distance away, and then burned during what researchers believe was python worship practiced around 70,000 years ago, smashing the previous oldest-known rites by 30,000 years. Other scientists feel that more research is needed and even argue that there was no ritual. Yet, throughout the Tsodilo Hills, home to Rhino Cave, rock art shows the San engaged in acts resembling the ceremony. The handling of the spearheads and quartz flakes is previously unknown behavior documented for the first time in Rhino Cave.

9 The Liang Bua Teeth

A case of hobbit murder might be afoot. Ever since the diminutive hominid Homo floresiensis was documented in 2003, scientists have pondered why they swirled down the extinction drain. Now, a toothy find could clinch the case. Two human molars turned up in 2010 and 2011, respectively, in the Liang Bua cave on Flores. This is the same cave where the only known hobbit remains were excavated years before. The Homo sapiens snappers slightly postdate the hobbits’ final bow, which experts claim happened 50,000 years ago. Humans already lived in Southeast Asia by then, making an overlap of the two species possible. They might even have interbred or competed for food—although the 1-meter-tall (3 ft) hobbits hardly qualified as opponents. Most likely, the humans obliterated their smaller cousins. There is additional evidence that the arrival of hunter-gatherers wiped out more than H. floresiensis. Several animal species also disappeared from the island around the same time.

8 Earliest Winery

The world’s oldest shoe is a perfectly preserved moccasin, despite its 5,500 years. It also led to the world’s earliest winery near the village of Areni. Returning in 2007 to the Armenian cave where the footwear was unearthed, archaeologists found equipment for producing ancient alcohol. There were dried vines, vats for trampling grapes by foot, storage containers for fermenting the juice, and tasting cups. The complete production line is over six millennia old. The large-scale factory indicates that the grape was domesticated earlier than thought, which is not impossible, considering the location. DNA studies have traced the beginnings of winemaking back to Armenia and surrounding countries. The prehistoric winemakers left their shoes and equipment but no clue as to who they were. Apparently, they kept their dead involved. A cemetery surrounds the site, with drinking vessels around and even inside the graves.

7 Witchcraft Island

An island near Sweden is wrapped with legends of the dark arts. Removing a rock from Bla Jungfrun will guarantee lifelong bad luck, and the island is best avoided on Easter, because that’s when the witches arrive for some Devil worship. These ancient beliefs may hold a grain of truth. You might not be cursed for life for stealing a stone or witness a holiday witch convention, but some people once took rituals seriously on Bla Jungfrun. Archaeologists visited the uninhabited island in 2014 and were astonished to find that 9,000 years ago, Stone Age ritualistic activity was rife. People traveled there specifically to partake in these rituals, and two caves in particular were adapted for this purpose. One contains an altar-type construction to perhaps prepare religious offerings. A fireplace lies in the other, beneath a large hollow hacked from one of the walls. The entrance to this cave offers a theater view of below. Researchers speculate that, together, the blazing fire and the hollow being enlarged was an act viewed by audiences for some unknown reason.

6 Cave Of Games

The Promontory culture, forerunner to the Apache and Navajo nations, settled in a cave near Utah’s Great Salt Lake. During excavations in the 1930s and 2010s, an aspect of this mysterious people came to life in magnificent numbers: They loved gambling. Hundreds of gambling aids showed that the Promontory competed with guessing, chance, and physical prowess. Women’s games consisted mostly of what were essentially dice matches, using split canes marked with burns and playing for low-risk wagers between them. Even so, these were social times, avidly followed by the men, who placed bets. Male games ranged from domestic recreation (such as seeing who could shoot a dart first through a moving hoop) to interactively forging bonds with other tribes. The Promontory flourished in the late 1200s, while their neighbors faced drought and famine. Gambling while sharing feasts with their neighbors likely created better relations and prevented raids. The rich variety of Promontory games is unmatched in Western North America and could have been the key to their success as a peaceful culture.

5 Hellenistic Petra

The ancient capital of the Nabataeans has a canyon cave complex known as Little Petra, not far from the more well-known Petra. This second site served as a getaway for wealthier citizens. In the main chamber and a connecting compartment awaited a discovery that still shocks scholars since its find in 2007. Wall paintings may not sound like much, but the quality and rarity of these 2,000-year-old Hellenistic scenes shook everyone. There are no complete artworks bearing this style, leaving almost nothing of the color and composition of the great masterpieces to study. Little Petra’s paintings could change that. Restoration took three years, but what emerged was an exceptional slice of this lost style. Exquisite realism allowed the identification of plants, birds, and insects. Children play flutes, collect fruit, and shoo birds away. The extensive range of colors were made even more luxurious with the addition of gold leaf and glazes. The wall paintings are now considered the best examples of Nabataean art and are the only figurative paintings that survive at Petra.

4 The Lupercal

The Lupercal (or Lupercale) is part of Rome’s intricate past, where legend and history often overlap. It is the city’s most sacred site, since it involves the twin brothers Romulus and Remus. Said to be the founders of Rome, the children were supposedly raised by a she-wolf in a cave known as the Lupercal. In 2007, an Italian team of archaeologists located a cavern 16 meters (52 ft) under the Palatine Hill. Part of it had already collapsed, and the fragility of the site prevented a full-scale excavation, but endoscopes and scanners revealed details about the inside of the grotto. Decorated with marble and seashells, a round space measures 8 meters (26 ft) high, with a diameter of 7.5 meters (24 ft). The best evidence that this is the Lupercal comes from its location as well as a white eagle insignia within the vault. Emperor Augustus, who died in AD 14, is said to have restored the holy site, situated near his palace, and added such an eagle. Indeed, this grotto lies beneath the ruins of where Augustus once lived.

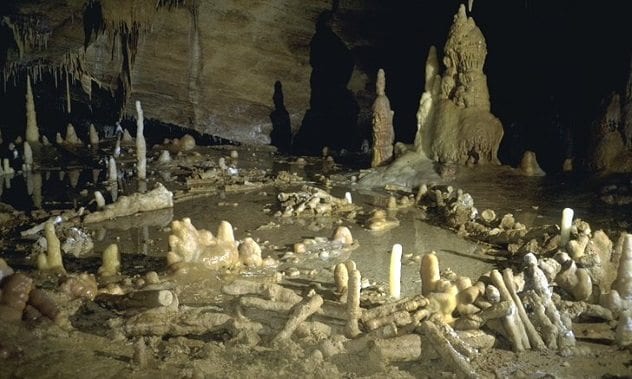

3 Neanderthal Builders

Neanderthal achievements aren’t bad for a hominid still viewed by many as brainless animals. They produced stone tools, glue, clothing, and jewelry, They used fire and shelters, and there’s evidence that their dead were buried with ritual. Their greatest and most mysterious act came to light in the 1990s. Cave explorers were 300 meters (984 ft) into the Bruniquel cave in France when they stumbled upon strange formations. Almost 400 stalagmites had been used as building material to construct walls. The most extraordinary are two ring-shaped walls, the biggest running 7 meters (23 ft) across and 40 centimters (16 in) high in places. Building occurred 175,000 years ago, and Neanderthals were the only human branch that lived in Europe during that time. This unique display proves once again that they were more intelligent than is generally accepted. The walls were erected in a place of total darkness, which might explain scorch marks found on the inside, as if hearths burned within. Researchers still don’t know the exact purpose of the stalagmite structures or if building underground was something that Neanderthals normally did.

2 Buddha’s Life

In 2007, an international team archaeologists was restoring murals at a Nepalese monastery and asked the locals about ancient art in the area. The kingdom of Mustang, once a part of Tibet, has managed to keep its Tibetan and Buddhist heritage unscathed throughout history. This interested the team very much. A shepherd recalled something he’d seen as a child and led them to a cave. After scaling a 3,400-meter (11,200 ft) height to reach the site, the researchers received the treat of a lifetime. Inside the cavern were 55 untouched paintings showing the life of Buddha. The scenes were full of color and were done by skilled artisans showing a strong Indian influence, rather than Tibetan. At the same time that the 12th- to 14th-century works were discovered, another religious treasure, ancient Tibetan manuscripts, were found in nearby caves. It’s possible that the area was a Buddhist school or retreat. The exact location of the paintings is being kept secret to prevent looters from making off with the rare collection.

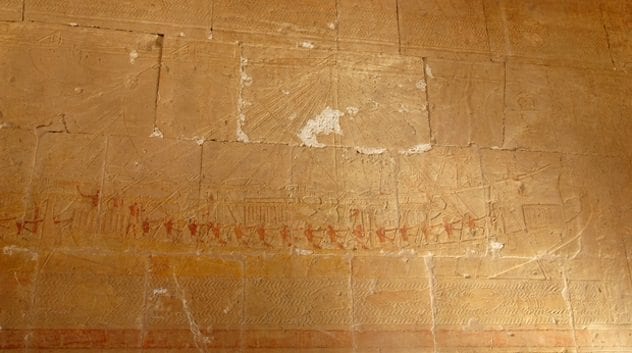

1 Egypt’s Lost Fleet

Wall carvings discovered at an Egyptian temple in the 19th century showed cargo ships returning from a legendary land called Punt. In 2004, archaeologists found the missing fleet. Eight caves near the Red Sea held the remains of equipment, ships, and a harbor community. Incredibly, the vessels were built to be assembled like puzzles, something nobody had ever done before. From the harbor oasis, Mersa Gawasis, great sea voyages were launched. When a 20-meter (66 ft) replica was made, the dubious-looking ship was essentially a giant hull without a frame and made from immensely thick wood. Sailing on the Red Sea for weeks, it performed with agility, surfed out a storm, and reached 16 kilometers per hour (10 mph). Perhaps more tantalizing than proving that ancient Egypt was a phenomenal maritime nation is the link between Mersa Gawasis and the mythical Punt. Among the artifacts were stones inscribed with factual-sounding accounts of sailing to Punt. The harbor was abandoned after four centuries, and everything was sealed up in caves. After 4,000 years, the historic rediscovery includes some of the oldest seafaring ships. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages