10Pompeian Prostitutes

Many depictions of Ancient Rome show it as a glittering citadel of white marble. In fact, the Romans were as earthy and real as any living people. The proof of this can be seen engraved in the walls of Pompeii. The ancient city was destroyed by a volcanic eruption that ironically preserved it far better than any other Roman site. Pompeii boasted an impressive number of brothels to cater to all tastes. These houses can be recognized from the stone beds packed into tiny rooms and erotic frescos showing guests what was on the menu. When customers staggered out into the street, or even while they were engaged in their cubicles, they liked to leave notes about the joys of their visit. “Hic ego puellas multas futui,” one man wrote—“Here I have f—ked many girls.” Anothers left a review: “Murtis bene felas”—“‘Myrtis, you suck well.” “Rufa ita vale quare bene felas.”—“Rufa, may life be as good as your sucking.” Not all customers were as pleased with their service: “Sabina felas no belle fasces.”—“Sabina you are sucking it, but not well.” One man seems to have become disillusioned with the whole profession, as this graffito on a brothel shows: “Weep, you girls. My penis has given you up. Now it penetrates men’s behinds. Goodbye, wondrous femininity!”

9Medieval Church Graffiti

The medieval church was powerful in a way that today’s churches can only dream of. We might imagine that this would lead to them being inviolable, but even a cursory glance at medieval churches will show how untrue this is. Any surface in reach is likely to be marked in some way—in either pious devotion or distracted doodling. Some of the graffiti looks as if it was inspired by the sermons the vandals were listening to. Crosses, angels, and the Virgin Mary all appear etched into the walls and pillars of churches. Perhaps this was a form of worship for those unable to speak the Latin of the mass or too illiterate to write out their faith. Other forms of graffiti speak of graffiti as prayer. Medieval ships are a common motif. It has been suggested that these may have been made as a form of prayer of protection for those on the sea. Portraits of individuals also turn up. Kings and queens often feature, as do saints, but images of common men and women can tell us lots about the clothes and appearance of people who would otherwise be forgotten.

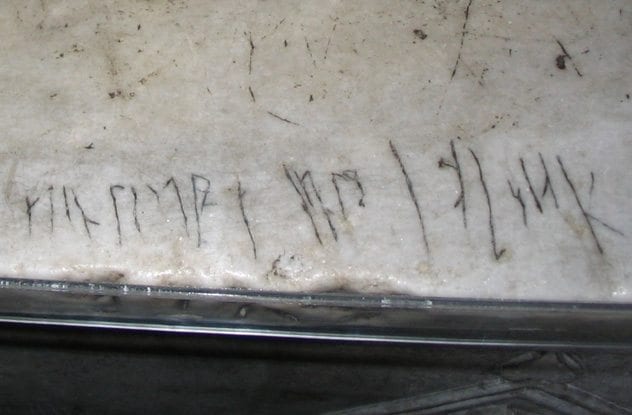

8Vikings—Hagia Sophia

Sometimes, graffiti can be deeply revealing about the world of those who made it, and sometimes, it is more revealing of human nature itself. The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul is one of the grandest religious structures in the world. It was begun in 532 and has been a church, a mosque, and museum over the course of the centuries. It has also been a writing pad for Vikings. On a marble banister is a string of runes left at some point in the ninth century. While the years have worn it away, the name Halfdan can still be made out. One reading of the rest of the inscription could be that it simply says “Halfdan was here.” In a different part of the building, another runic graffito has been found, badly eroded. All that can really be read is the name Arni or Ari—another Viking with a fondness for leaving his own name in stone. It seems likely that these men served in the Varangian Guard, an elite corps of troops used by the Byzantine emperors. This body was made up mostly of Scandinavians, who apparently brought their runic writings with them.

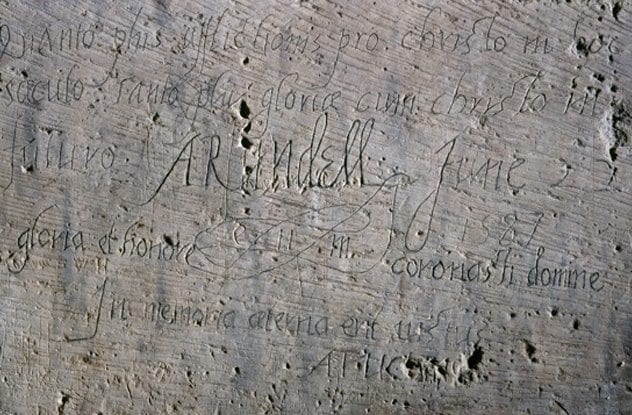

7Tower Of London

When people are locked up for long periods, graffiti can be a tempting way to pass the time. Just check out the desks in detention room. The Tower of London is a castle that has long been used by English monarchs as both a place of safety for themselves and a place to keep troublemakers out of the way. These noble prisoners often took their chance to leave a reminder of their existence in case they never walked out of the prison. Some of the graffiti is simply a name. A “remember me.” Others are whole sentences such as a Latin inscription left by Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel in 1587, which says, “The more affliction we endure for Christ in this world, the more glory we shall get with Christ in the world to come.” Noble crests and insignia also abound on the walls. Other prisoners seem to have undermined their defenses with their graffiti. One man who was imprisoned on a charge of sorcery took the time to scratch a detailed horoscope in his cell.

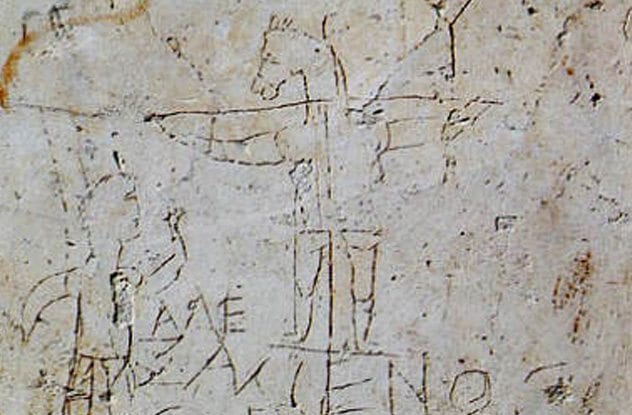

6Alexamenos Graffito

In 1857, an excavation on the Palatine Hill in Rome turned up a piece of graffito in the plaster of a wall. We’ve already seen that the Romans were not shy with the things they were willing to write on a wall, but it seems they were not afraid of blasphemy either. The Alexamenos Graffito, dating from around AD 200, may be the earliest depiction of Jesus—and it is not flattering. The Alexamenos Graffito shows a figure hanging from a cross with a man at the base looking up. Text, in Greek, says “Alexamenos worships his god.” What stops this being a standard image of the crucifixion is that the person on the cross has the head of a donkey. This shows some of the aggression toward the relatively new Christian religion that must have existed at the time. Tertullian, an early Christian author, refers to the idea that “our god is the head of an ass.” The graffito is also an important source on the act of crucifixion as it was made at a time when people would have seen criminals nailed up by the roadside.

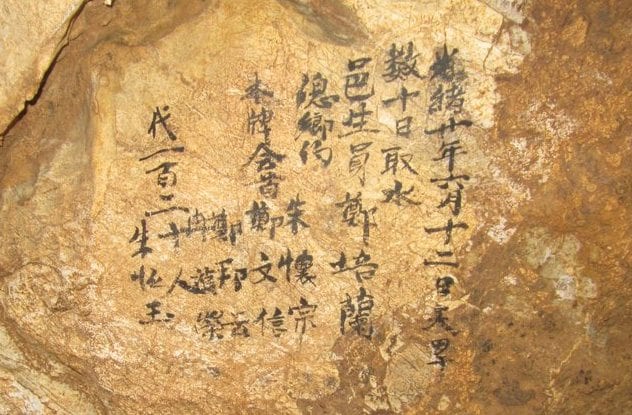

5Chinese Drought Graffiti

Not all graffiti is personal. In the Dayu Cave in the Quinling Mountains of China, there are the records of droughts suffered hundreds of years ago. When the rains failed to arrive, the local people would enter the caves to offer prayers for the end of the drought. The walls of the cave bear over 70 records of prayers offered, marked in black paint. One patch of graffiti reads “On June 8, 46th year of the emperor Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty (July 7, 1707AD), the governor of Ningqiang district came to the cave to pray for rain.” Another text tells of how a fortune teller joined in the ceremony. The precise dating of the graffiti has offered scientists a window into the climatic past of the region. By studying the minerals and chemicals in formations like stalactites in the cave they were able to calculate atmospheric conditions on the surface above the cave. They found that when locals were recording a drought, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels were relatively high.

4Hieroglyphic Graffiti

There are many mysteries surrounding the building of the pyramids in Egypt. There is still no consensus as to the exact method used to haul the blocks. We have learned that the men employed in the hauling were not slaves but hired workers. Graffiti is giving an extra insight into these men’s lives. Exploration of the Great Pyramid of Giza has turned up hieroglyphic graffiti in places that no one was ever meant to see. The men building the pyramid wanted to be a permanent part of one of the Ancient Wonders of the World. In doing so, they left told us how they were organized. Then people doing the heavy lifting on the pyramid were broken into small gangs of individuals. They received, or gave themselves, names like “Perfection gang,” “Great One,” “Green One,” and “Endurance.” One in the King’s burial chamber reads “The Friends of Khufu Gang,” Khufu being the pharaoh that the pyramid was raised to house for all eternity. From the placing of the gang signs on opposing sides of blocks, it seems that gangs were competing with each other for prominence. Naming the gangs of workers could have been a way of the overseers to create competition and improve efficiency.

3Witch Marks

There is a special type of graffiti meant to ward off danger. This type of protective magic symbol is called Apotropaic Magic. When you fear something is coming after you, you make a special sign in your home and it keeps them away. For the medieval mind there were few things as fearsome as the witch. Witches were scary in several ways. They were unruly women, and they had the powers of the devil at their disposal. Such symbols were commonly found in churches. Here, witch marks often took the form of daisy wheels—simple geometric designs drawn with a pair of compasses that look like flowers. Witch marks were also found in private houses. In the 17th century, King James I was convinced that witches were out to get him. At Knole House, where the king might have been expected to visit, signs were carved into the woodwork to ward off evil. V and M signs were made to invoke the Virgin Mary, and crisscross patterns were made as demon mazes—shapes meant to make evil beings get lost before they could harm visitors.

2Mayan Graffiti

The Mayan Society of Mesoamerica lasted for millennia until the Spanish conquistadors brought about its collapse. Its cities and temples are amazing works of architecture. It was one of the great world civilizations. Its writings are an incredible source of information about this lost world. But the archaeological are also great sources of graffiti that give windows into the lives of people in this lost world. At Tikal, drawings carved into the stone show portraits, dancing figures, animals, thrones, gods, and priests. One graffito seems to show an execution: a figure stands with his arms stretched between two poles while another has just shot him with an arrow, or run him through with a spear. There are also valuable images of a procession. Men carry trumpets with ribbons streaming from them, while others follow behind. All of these details would be lost if people had not decided to deface their local monuments.

1Piraeus Lion

Piraeus was the port of Ancient Athens. From the first or second century, it was guarded by a statue of a lion. The Piraeus Lion became so famous that the port was known as Porto Leone—the Lion Port. This statue, originally sculpted in the fourth century BC, remained in place until the 17th century when the Venetians plundered it and took it home to Venice. All that history would seem to be sufficient, but one puzzle persisted—what was the strange writing on the sides of the Lion? In the 18th century, a Swedish diplomat recognized the marks for what they were: Viking runes. The Varangian Guard had struck again. These Scandinavians had written a lengthy inscription in the shape of a dragon into the Lion’s side. The runes are hard to read, but one translation of them reads as follows: “They cut him down in the midst of his forces. But in the harbor the men cut runes by the sea in memory of Horsi, a good warrior. The Swedes set this on the lion. He went his way with good counsel, gold he won in his travels. The warriors cut runes, hewed them in an ornamental scroll. Askell (and others) and Thorlaeifr had them well cut, they who lived in Roslagen. (Unreadable) son of (Unreadable) cut these runes. Ulfr and (Unreadable) colored them in memory of Horsi. He won gold in his travels.”