With credit to researchers who have studied the fossils of the Meg, we now know more about this nightmare of the ocean than ever before. Although the facts are fascinating, they are far from comforting. Megalodon was a shark ripped right from a monster movie.

10 Most Recent Sightings

On Earth, there are five large oceans covering 71 percent of the surface and holding over 1.3 billion cubic kilometers (312 million mi3) of water. With that size in mind, it’s no surprise that we have only mapped less than ten percent of the global ocean using modern sonar technology. We really might not know what is lurking underneath the water’s surface. In 1928 and 1933, sightings of a “monstrous” shark greater than 12 meters (40 ft) in length were reported off the coast of Rangiora, New Zealand (by the same people both times). Most notably in 1918, Australian naturalist David G. Stead spoke to men who were fishing near Broughten Island, New South Wales. They revealed to him that a shark the size of a blue whale had turned up and devoured all of their crayfish pots, which were approximately 1 meter (3.3 ft) in diameter. The men explained that as the shark passed by, the water had “boiled over a large space,” and they were too afraid to return to the water.[1] Despite these recent sightings, experts still believe the Meg went extinct 2.6 million years ago.

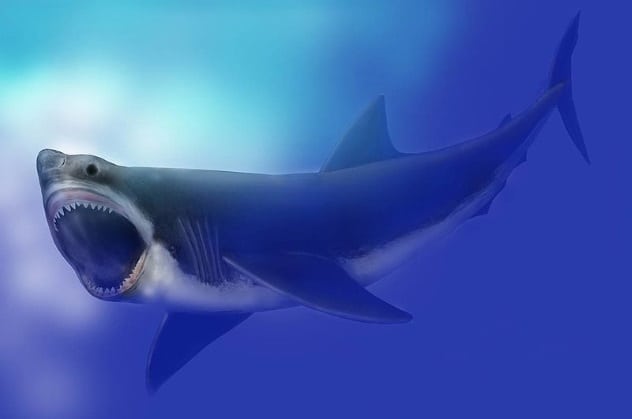

9 Powerful Predator

The average megalodon weighed 50 to 70 tons and measured roughly 11 to 13 meters (36–43 ft) in length, but the largest individuals weighed possibly as much as 100 tons and may have reached up to 20 meters (66 ft) long. Either way, megalodon was one of the most powerful predators in the water. If you imagine razor-sharp teeth attached to a beast the size of a double-decker bus, then that’s what we’re working with here. Kronosaurus and Liopleurodon from the Mesozoic Era were big but not even close to this size, as they only weighed in at a maximum of 40 tons. The killing method of the Meg was brutal; unlike other sharks that would attack the soft tissue of their prey like the underbelly or fins, megalodon was able to bite right through the bone. One whale fossil discovered by scientists showed compression fractures from below, caused by the Meg ramming its head into the soft belly of the whale, which would stun the prey before it was devoured. Scientists also believe megalodons traveled in groups, allowing them even more power in numbers.[2]

8 The Name ‘Big Tooth’

The name “megalodon” translates to “big tooth,” and it certainly lived up to the name. The teeth range in size from 7 to 18 centimeters (3–7 in), and tooth hunters are always on the lookout to find more for their collections. However, an 18-centimeter tooth for sale is rare, and only a handful have ever been found, so they command price tags into the tens of thousands of dollars.[3] The 8-centimeter (3 in) teeth of the great white shark would be baby teeth to the Meg. This beast of the oceans would lose its teeth rapidly, dropping as many as 20,000 in its lifetime, often from biting into prey. Luckily, they had five rows of teeth, so there were always plenty of back-ups. Most megalodon teeth that are sold online will have been worn down from excessive feeding, proving this was one giant that was always hungry.

7 Feasting On Humpback Whales

When you’re a big beast, you’re going to have a big appetite. The open jaws of the Meg could measure up to 3.4 meters by 2.7 meters (11 x 8.9 ft). They would feast on prey of all different sizes, from smaller animals, including dolphins, sharks, and sea turtles, right up to large humpback whales. Due to their powerful jaws, with a bite force of between approximately 110,000 and 180,000 Newtons, the Meg could do severe damage to a whale’s skull. Fossilized whale bones have been recovered with the Meg’s teeth marks etched on the surface, showing their eating habits millions of years ago. Some bones even have the tips of the teeth still embedded, which had likely broken off during a feeding frenzy. Today, great white sharks will still attack humpback whales, but they tend to prey more on the calves, adults who are sick, or those in distress for an easier kill.[4]

6 They Were Not Uncommon

During the peak of their existence, megalodons could be found in oceans all around the world. The remaining fossils that belonged to these monsters have been found in North and South America, Europe, Africa, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Jamaica, the Canary Islands, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Malta, the Grenadines, and India. If it was underwater at the time and there was food to be had—you can bet a Meg lived there. They also had a long life span of around 20 to 40 years, but the healthiest and best-fed megalodons would live for even longer.[5] Another advantage they had was being a homeothermic animal, which meant they were able to maintain a stable internal body temperature regardless of their environment, so the oceans were without limits for them. Although it’s unlikely we might come across a megalodon ever again, let’s not forget that the Yeti crab was only discovered in 2005, when explorers took a submarine 2,200 meters (7,200 ft) below the surface to find them living on hydrothermal vents. Never say never.

5 They Were In Shallow Waters

It’s difficult to believe that a beast the size of the Meg could be found anywhere but the deepest parts of the ocean. However, recent findings prove that they did venture close to shores to give birth, as these predators preferred to do so in the shallow, warm waters close to the coasts. Researchers at the University of Florida confirmed they had discovered fossils from a ten-million-year-old megalodon nursery located in Panama. They found more than 400 fossil teeth, collected from the shallows, which belonged to juvenile Megs. Other nurseries were found in the Bone Valley region of Florida and the Calvert Cliffs in Maryland. Although the newborns were still big in size, averaging 2.1 to 4 meters (7–13 ft), they were still vulnerable to predators, such as other sharks. As a newborn in the ocean, almost nowhere is safe, but megalodons did their best to give their young a winning chance.[6]

4 They Were Fast

Not only was the Meg huge—it was also really fast. In 1926, researcher M. Leriche made a breakthrough discovery, uncovering a vertebral column of a single megalodon containing 150 vertebral centra. From this, megalodon researchers were able to learn more about the behavior of this giant shark. Due to the shape of the spine, the Meg was able to lock prey in its powerful jaws and then viciously shake it side to side as the flesh would tear from the bone. This is what made them so dangerous in the water—once they had their prey, there was no escape. Also, due to their shape, they were able to reach speeds of at least 32 kilometers per hour (20 mph), which is remarkable considering their gigantic size.[7] (Their cruising speed has been estimated at 18 kilometers per hour [11 mph].) Such speeds would have allowed them to outswim many species. Dr. David Jacoby, from the Zoological Society of London, explained, “The megalodon was an enormous apex predator that appeared to cruise the oceans at speeds unrivaled by any shark species present today.”

3 They Likely Starved To Death

Although there’s no solid evidence linked to exactly why the megalodon went extinct, it’s strongly believed that their huge appetite became problematic for them. Around 2.6 million years ago, the sea levels rapidly changed, and that had a remarkable impact on the Meg’s food sources. About a third of all large marine mammals became extinct at this time, and any spare food would have been consumed by smaller, more agile hunters of the ocean. Basically, the competition was fierce, and the Meg needed an enormous amount of bait just to maintain their body temperature for survival. The Meg’s population peaked during the middle of the Miocene Epoch, which occurred 23 to 5.3 million years ago. They were found mainly near Europe, North America, and the Indian Ocean, but toward the beginning of their extinction, during the Pliocene Epoch 2.6 million years ago, they had begun to travel further into the South American, Asian, and Australian coasts.[8]

2 They Were Once Mistaken For Dragons

In the 17th century, Danish naturalist Nicholas Steno identified the teeth of megalodon. Before that, the fossilized teeth were called “tongue stones” and believed to be from dragons or large snakes known as “serpent dragons.” It was widely believed that a dragon would lose the tip of its tongue through combat or in death, and it would turn to stone. The teeth—or tongues—would be collected by peasants, as they believed they protected them against snakebites and poisoning. When Steno revealed that these were megalodon teeth and not the tongue tips of dragons, it was the beginning of the dissipation of the myth that dragons did once exist. Instead, there were even bigger monsters now to be worried about.[9]

1 Mega-Debacle

In 2013, when everyone thought it was safe to get back into the water, the Discovery Channel released a mockumentary titled Megalodon: The Monster Shark That Lives. Aired during their popular Shark Week, the program ran “footage” of megalodons, including an “image from WWII archives, of a giant shark with a 64 foot tail to dorsal fin span.” It’s fair to say the shark-loving community was not impressed. American actor Wil Wheaton said: Last night, Discovery Channel betrayed that trust during its biggest viewing week of the year. Discovery Channel isn’t run by stupid people, and this was not some kind of mistake. Someone made a deliberate choice to present a work of fiction that is more suited for the SyFy channel as a truthful and factual documentary. That is disgusting, and whoever made that decision should be ashamed. The mockumentary might have been fake, but the angry reaction was very much real.[10] Cheish Merryweather is a true crime fan and an oddities fanatic. Can either be found at house parties telling everyone Charles Manson was only 5ft 2″ or at home reading true crime magazines.Twitter: @thecheish Read More: Twitter Facebook