SEE ALSO: 10 Current Fads That Are Way Older Than You Think

10 Women wore their finest jewelry (into the afterlife)

Archaeologists dug up some 5th and 6th-century bodies from a cemetery in Lincolnshire found the women therein dressed for a grand party. Intricate brooches and silver buckles fastened their elegant clothes. And various jewels adorned their bodies, like silver rings and resplendent necklaces, containing hundreds of pieces of rock crystal, amber, and glass. The women were also buried with tweezers, to maintain their hygiene in the hereafter. But the flashiest accessories were fabric bags propped open by elephant ivory rings from sub-Saharan Africa, “which might as well have come from the moon,” given their rarity.[1]

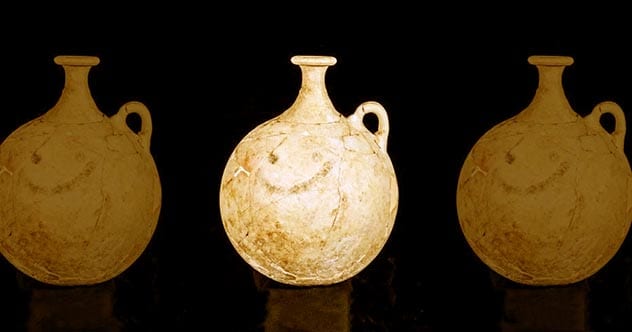

9 The Hittites “invented” the smiley face emoji

The Hittites ruled areas encompassing Greece, Egypt, Turkey, and Syria during their heyday, around 1700 to 1200 BC. They excelled as charioteers and, surprisingly, invented the smiley face that now adorns countless objects. The Hittite emoji decorates a nearly 4,000-year-old jug, which once held a sweet beverage called sherbet. It’s one of many similar pieces of pottery ware found on the Turkish-Syrian border at Karkam??, where the biblical Battle of Carchemish occurred in 605 BC. The jug has no historical or regional analog. It’s a unique piece and the oldest-yet-discovered smiley face of its kind (or a masterful piece of archaeological trolling).[2]

8 Medieval VIPs flaunted their wealth with cutlery

Medieval cutlery was much fancier than contemporary cutlery, as evidenced by a 500-year-old ornamented spoon found in Suffolk. The gilded, silver spoon handle dates to 1300-1400 and depicts the “Wild Man, a “barbaric, chaotic, unrestrained” mythical figure who dates back to at least the 9th century in Spain. And while spoons are nowadays owned but just about everybody, this aged piece belonged to some wealthy, medieval hotshot. Up until the 15th century, most depictions of Wild Man appeared on manuscripts and literature but not as decorative objects. Until this Middle Ages rich dude came along and blew everybody’s mind.[3]

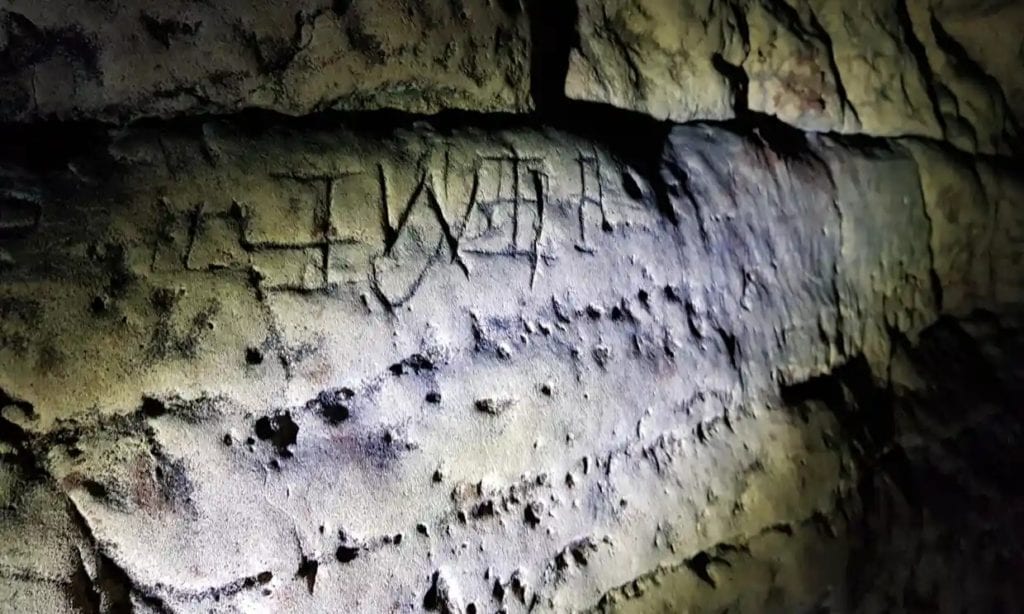

7 Anti-Witch markings were functional art

A bunch of weird, 17th and 18th-century markings inside the caves at the Cresswell Crags in England are a perfect example of functional art. Researchers initially thought the markings, which include letters and also designs, like boxes, mazes, and diagonal lines, were the work of graffiti artists. But they’ve turned out to be the most extensive collection of apotropaic marks in the UK. Apotropaic symbols supposedly averted evil and are usually found in domestic settings. That they were inscribed in these caves, to repel witches and ghouls and demons, suggests the area was thought to be an infernal gateway.[4]

6 Egyptians displayed their social superiority with tattoos

Infrared scans revealed that two 5,000-year-old Egyptian mummies previously unearthed in Gebelein, near Luxor, are decorated with the world’s oldest figurative tattoos. And since one of the mummies is male, it corrects the previously-held belief that only women rocked tattoos in Pre-dynastic (aka old-timey aka before the first pharaoh, circa 3100 BC) Egypt. The female mummy received four strange, S-shaped markings on her right shoulder as well as (probably) the image of a baton used in rituals. The male mummy’s ink represents two massively-horned animals, perhaps a wild bull and a Barbary sheep. These pre-hieroglyph era tattoos were inscribed in soot and signified high social standing, bravery, virility, or arcane knowledge of enchantments.[5]

5 Roman households had sumptuously-decorated shrines

The Great Pompeii Project recently uncovered yet another cultural treasure, the swankiest personal shrine ever found inside a Roman dwelling. The 16-by-12-foot room is a place for worshipping local gods and guardian spirits. It’s stupid with frescoes depicting magical beasts and divine nature scenes, as well as strange iconography like a wolf-headed, Roman version of Anubis and lots of eggs, symbols of fertility. It also features a garden area with a raised pool, undoubtedly built at great expense by some wealthy Pompeiian. Just about every Roman dwelling had such a room, known as a lararium. But this one was luckily (though not for its owner) preserved by volcanic ash.[6]

4 Levantine people prized purple

Tyre and Sidon in Lebanon were the primary producers of the rare and valued purple dye during the biblical days. But archaeologists had never found any direct evidence of its manufacture. Until now, in some ruins at Tel Shikmona, near Haifa in Israel. The former Byzantine settlement held a massive dye-works facility, which occupied five dunams (one acre) of the city’s 100 total dunams during the Iron Age (11th to 6th centuries BC). And that’s why the city was positioned so precariously upon a godforsakenly barren and inaccessible promontory: because murex snails live on rocky coasts. Purple dye was made from snail-glands at a conversion rate of thousands of snails per kilogram of dye. And that’s why the ancients considered it a “royal” color, available only to the fabulously wealthy, the nobility, and the high priests.[7]

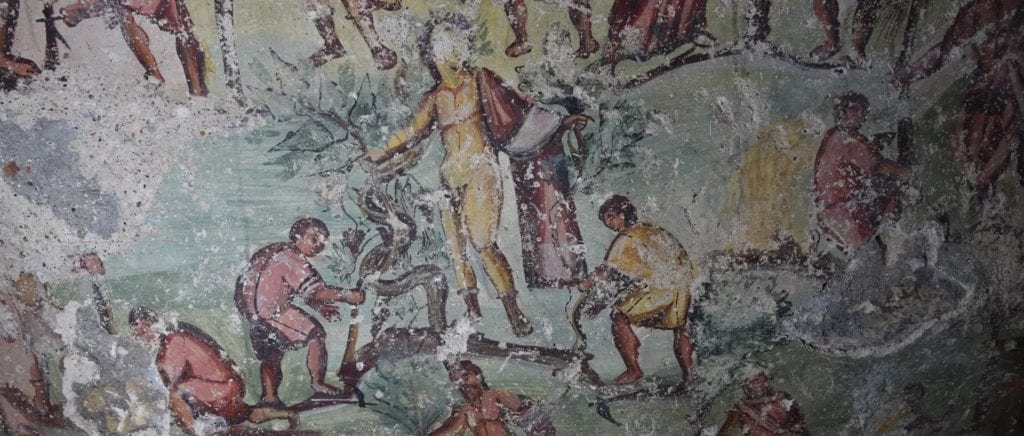

3 Tombs were decorated with fabulous “comics”

A 2,000-year-old tomb in Beit Ras, Jordan, is decorated with a pictorial civic history lesson. Two millennia ago the city was named Capitolias, after the patron deity Jupiter Capitolinus. Capitolias belonged to the Decapolis, ten Hellenistic-Roman hybrid cities lining the outskirts of the Roman Empire. The tomb’s walls and ceiling are awash in frescoes that feature about 260 figures. It shows the city’s birth, depicting the initial offering made to the eponymous patron deity Jupiter Capitolinus. The following scenes reveal that the gods’ influence in helping the peasants tend their fields, fell trees, and erect ramparts. Finally, priests show up again, making another offering to thank the gods for the awesome new city.[8]

2 Denisovans used colored pencils

Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains in Siberia is special. Therein was found the first-ever Denisovan bone fragment, from the 41,000-year-old “X Woman.” The Denisovans are still poorly understood, though they’re most closely related to native Australians and Papuans. More recently, researchers stumbled upon ancient artforms inside Denisova Cave, including jewel-like beads, bands, and a mammoth bone tiara. Among these, they also found the equivalent of a crayon or colored pencil. It’s a little chunk of hematite, a natural reddish-brown pigment. The sediment layer it occupied dates from 45,000 to 50,000 years ago, suggesting these old-timey arts could have been developed by the enigmatic Denisovans.[9]

1 Ancient Mesoamericans commemorated the dead with huge statues

The ancient Mesoamericans revered their ancestors and sculpted towering, mystical statues to pay their respects. These 2,000-year-old statues from Guatemala are called “potbellies” due to their rotundness and gigantism, standing more than two meters high and weighing over 10,000 kilograms. Even cooler, they’re made of rocks that were magnetized by lightning strikes. The ancient artists picked out these prized specimens by holding a naturally magnetized rock next to these iron-rich, basaltic stones, which replied with a telltale magnetic repulsion. The figures are carefully sculpted so that only their heads and navels, considered sacred body parts, are magnetic. Via magnetism, the long-gone ancestors supposedly displayed their influence over the material world.[10]