Most of the men on this list aren’t well known, even though they’ve made history. Of course, they weren’t involved in as much dysfunctional fatherly drama as, say, homicidal Henry VIII who exiled his daughter Elizabeth and chopped off her mom’s head. But these fathers cared a lot about their kids, and through that caring they gave gifts to the rest of us.

10Amilcare Anguissola

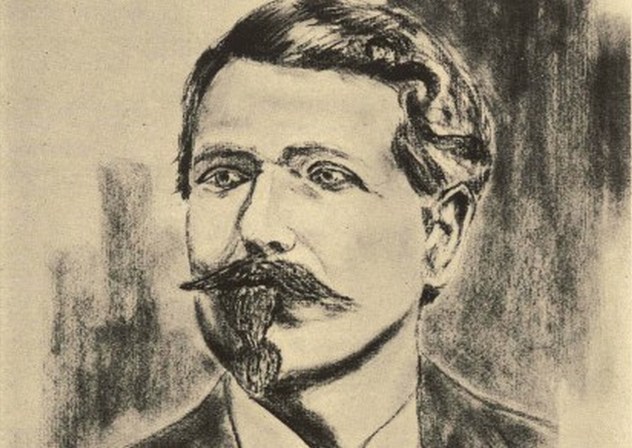

During the Renaissance, most aristocratic dads limited their daughters’ education to little more than music and needlework—two occupations designed to attract a husband who would bring wealth or status to the family. It was highly unusual for an aristocratic young woman to devote herself to any type of profession, even an artistic one like painting. Italian nobleman Amilcare Anguissola had six daughters and one son, but he gave all his children excellent Renaissance educations. In fact, when Amilcare recognized that his oldest child, Sofonisba, had an extraordinary talent for painting, he did more than just pay for her to study painting with a renowned artist—although even that was highly unusual. Amilcare used his influence to provide his daughter with the help and encouragement of Michelangelo, the greatest Italian master around. And rather than marry her off early, her father let Sofonisba develop her talent. The proud padre even publicized his daughter’s paintings to important men who could spread her reputation as an extraordinary artist. The training and support that Amilcare gave to his daughter enabled Sofonisba Anguissola to become the first great female painter of the Renaissance. As an aristocrat, she never sold any of her paintings, but she was asked to live at the palace of King Phillip II of Spain where she painted portraits of members of the court. Internationally acclaimed during her lifetime for their lifelike quality, Sofonisba’s portraits introduced a new informality and were the first to feature people who actually smiled. Sofonisba’s fame paved the way for other women artists, and her works were so good that they’ve been mistakenly attributed to the Renaissance’s great male artists like Titian and Leonardo da Vinci. One of Sofonisba’s famous paintings is the above portrait of a father with two of his children. The father is Amilcare Anguissola, immortalized by his daughter.

9Candido Jacuzzi

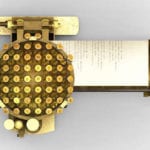

Candido Jacuzzi was the youngest of seven inventive brothers whose family left a small town in Italy for Berkeley, California in the early 1900s. By the 1930s, the brothers were the owners of Jacuzzi Brothers, Inc., which designed submersible pumps for agriculture. It was Candido who made “Jacuzzi” a household word after a devastating illness struck his son. In the winter of 1942–43, Ken Jacuzzi wasn’t quite two years old; he caught a fever that eventually left him crippled “from neck to knees” with systemic juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Candido sold off property so that he could afford to spend more time at home with Ken. He paid for physical therapists and all kinds of cures—everything from goat’s milk to gold injections—though nothing seemed to work. But Candido found a real chance to make a difference for Ken when doctors discovered that hydrotherapy helped relieve the child’s pain. The nearest hospital with a hydrotherapy unit was a long drive away, and Ken found the trip exhausting. So Candido went to work redesigning a sump pump that pulled water out of basements to create a water jet. Then he added an air inlet mixing the water and air that shot from the jet. The resulting pump created a whirlpool in the family bathtub, so Ken could have frequent hydrotherapy at home to relieve his pain. Doctors were pleased at how well the boy’s blood was circulating. It kept his limbs from atrophying. Dad was glad he was finally helping Ken. At the request of a doctor, Candido patented his invention and sold it for medical use. In 1966, he invented a tub with a built-in pump and was issued a patent for the first version of the Jacuzzi “hot tub.” Eventually known simply as “Jacuzzis,” these outdoor whirlpools became popular throughout the world for recreation, and for giving their owners a “celebrity lifestyle,” a term that referred to Hollywood sexcapades. It’s likely that someone reading this very list owes his or her conception to Candido’s Jacuzzi.

8Joseph Friedman

In 1936, Joseph Friedman took his preschooler, Judith, to a soda fountain called the Varsity Sweet Shop in San Francisco and bought her a milkshake. Little Judith found it difficult to drink from her straw. The top of it was just out of her reach, but when she bent her straw to bring it closer to her mouth, the resulting crimp in the straw stopped the flow of the milkshake. That was when Judith’s dad thought of a way to make it easier for her to enjoy her treat. In his workshop, Joseph inserted a screw inside a straw, which in those days was made of heavy paper that was coated with wax. He wrapped dental floss around the screw threads to make grooves in the straw. Then he removed the floss and the screw, and he’d created ridges that allowed the straw to bend without interfering with the flow of the liquid. Now it was easier for his little girl to drink from a tall glass. Joseph was supporting his growing family (he had three more children after Judith) as a real estate broker. However, he’d been tinkering and inventing things since he was 14 years old when he’d come up with the “pencilite”—a lighted pencil that could write in the dark. Realizing that this bendable straw was one of his best inventions, Joseph patented it as the “drinking tube” in 1937. He tried to sell the patent. When that didn’t work out, he decided to manufacture the straws himself. In 1939, he started the Flexible Straw Corporation, which later became the Flex-Straw Company. Judith remembers her father telling her that someday the invention she’d inspired would be used all over the world. And, of course, his prediction came true. Millions of flexible straws are manufactured every year and distributed internationally.

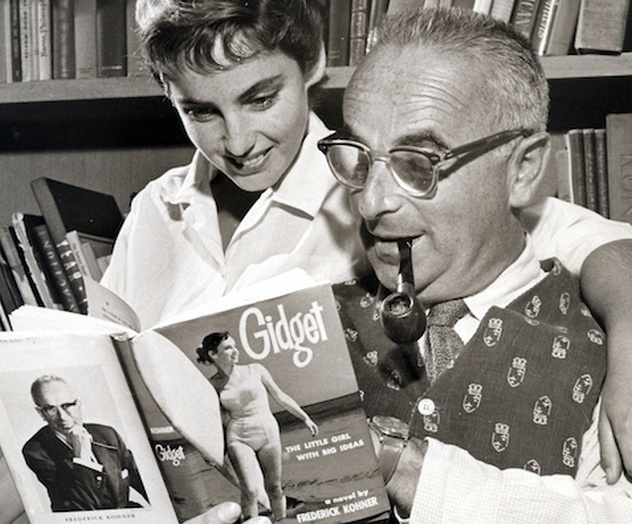

7Frederick Kohner

In 1933, Frederick and Franzie Kohner fled Europe to escape Hitler. Frederick became a successful screenwriter, and the couple wound up in Brentwood where their youngest daughter, Kathy, grew up as a California girl. In 1956, Kathy Kohner had trouble adjusting to high school, and her escape was the Malibu beach. At the time, Kathy was absorbed by two things—the thrill of riding the waves and a crush on a cute guy who surfed. Surfing was a sport reserved for men, but Kathy didn’t care. She practiced her skills and brought peanut butter sandwiches to the beach to ingratiate herself with the surfing crowd. Most of the regulars had nicknames like “Jaw,” “Moondoggie,” or “Golden Boy.” When the guys nicknamed the 155-centimeter (5″1′) Kathy “Gidget,” for “girl-midget,” Kathy realized she’d been accepted. Kathy’s friends didn’t know much about surfing (a classmate wished her luck with her water skiing), so Kathy confided her enthusiasm to her dad who was “a good listener.” When she decided to create a book about her surfing buddies, she told her dad her surfing stories, and Frederick turned them into readable fiction. The result was Gidget: The Little Girl with Big Ideas. The book was told from a teenage girl’s point of view, and it was so authentic that some people thought Frederick had stolen his daughter’s diaries—though Kathy explained that she and her dad had such a close relationship that she actually told him a lot of the same stories that were in her diaries. Frederick also wrote a screenplay for the 1959 film, Gidget, starring Sandra Dee, which was a huge hit. There was a TV version of Gidget with Sally Field; there were book and movie sequels—even a comic book. By the time Kathy came home from college in the 1960s, the Malibu scene had “gone crazy.” Inspired by Gidget and the beach party movies that followed, hordes of teens had flocked to the California coast. Dudes and dudettes were paddling out to sea on their boards, and surfing was becoming a coed, mainstream sport.

6Chiune “Sempo” Sugihara

In 1939, Chiune Sugihara became the Japanese Consul General in Lithuania. By 1940, the Germans were conquering Europe and enslaving and massacring Jews. In July of that year, Jewish refugees from Poland began showing up in front of Lithuania’s Japanese consulate begging for visas so that they could get out of Europe before the Nazis caught up with them. Chiune wrote to his superiors for permission to issue the visas, but the answer was “no.” Chiune knew he risked disgrace and possible imprisonment if he illegally issued visas. There would surely be consequences for his family, so Chiune included them in the decision-making process. Chiune’s oldest son Hiroki would later tell how his father had carefully explained that the people standing outside their gates needed help so that they wouldn’t be killed. “Help them,” the boy urged. With fighting coming closer, the Japanese consulate was closing, but until his departure, Chiune (with his family’s help and support) spent nearly every waking moment issuing over 2,100 visas for Jews and their families. After the war, Chiune was disgraced, forced to resign, and struggled to find steady work. But although the ex-diplomat never spoke publicly in Japan about the events in Lithuania, he’d saved over 6,000 lives, and grateful Jewish survivors were searching for him. In 1985, Chiune was honored in Israel. Sadly, he died the following year without the world knowing much of his story. Those life-saving visas might have been remembered only by the survivors, but Hiroki—with both admiration for his father’s courage and pride in his own support of his father’s decision—spent much of his life publicizing Chiune’s courage. That publicity has allowed many to get to know and be inspired by the man called the “Japanese Schindler.” A short film based on Chiune’s life, Visas and Virtue, won an Oscar in 1997.

5John Holter

In 1955, John Holter became a dad, but it wasn’t the joyous occasion he’d looked forward to. His son Casey was suffering from hydrocephalus. This meant that his cerebrospinal fluid, which normally circulates around the brain and drains into the blood stream, was blocked from draining. Its buildup would cause brain damage and eventual death. There was no known, effective treatment. At first, Casey was kept alive with a twice-a-day procedure: A needle was inserted into the soft spot on his head and a syringe pulled out the excess liquid circulating around his brain. When Casey grew older, a “shunt” was implanted under his scalp to remove excess cerebrospinal fluid. Unfortunately, this shunt had problems, because its valve often failed. John wasn’t a doctor or even a college graduate. He was a machinist, or “knuckle-knicker,” as he called himself. But, determined to save his son’s life, John invented a prototype superior to anything medical science had ever seen—even though it was only a flexible tube that, on each end, featured an attached rubber condom with a slit in the top. The genius of the device was that those slits in the condoms worked like the nipples on baby bottles. When pressure built up from too much fluid around the brain, the slit opened so the cerebrospinal fluid could drain into the bloodstream. Once the pressure had been relieved, the slit closed, so blood and contaminants didn’t flow back into the fluid around the brain. Casey’s neurosurgeon approved the valve design, but John needed a material that could safely be used inside the body. He found a “new” material called silicon and rushed to produce his device in time to save his son. Unfortunately, only days before the invention was ready, Casey needed an operation, and the inferior shunt was implanted. The operation caused brain damage, and Casey died of a seizure a few years later. Meanwhile, another child who was implanted with John’s device recovered. John quit his job to manufacture his invention, which has saved the lives and mental health of hundreds of thousands of babies.

4Amasa Coleman Lee

The most admired lawyer in American literature is Atticus Finch from To Kill A Mockingbird—a Pulitzer Prize–winning novel that has sold millions of copies worldwide. The movie version of Atticus Finch (played by Gregory Peck) is the number one hero on the American Film Institute’s “Greatest Heroes & Villains” list. To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee takes place during the Depression, when segregation and the inferiority of black people were taken for granted in the South. Against that background, Atticus’s brilliant defense of a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman has helped fight racist attitudes in America—and inspired thousands of idealistic students to enter law school. According to Harper Lee, Atticus Finch was a fictionalized version of her father, Amasa Coleman Lee. Like Atticus, Amasa was a successful small-town Alabama attorney and state legislator. And, like Atticus, he had defended black men only to see them executed. But Amasa stood up to racism in the Jim Crow South. “My father,” Harper explained in one interview, “is one of the few men I’ve known who has genuine humility, and it lends him a natural dignity.” She has also said, “He believed that people are basically good, capable of improving, and as eager as the next person for a better future.” Amasa’s humility, dignity, and belief in people were all qualities that were so admired in Atticus Finch. The widower Atticus is also one of fiction’s favorite single dads. As both mother and father to his children, he guides them through troubles and teaches them to be fair and tolerant in an unjust world. In many ways, Amasa was also a single dad, because Harper’s mother—believed to have suffered from mental illness—was often emotionally unavailable to her daughter. Fortunately, Harper had the fond attention of a father who was always ready to talk to her if she visited him at his office or sat with him in the evenings to “help” him read his paper. Their close relationship created an American icon.

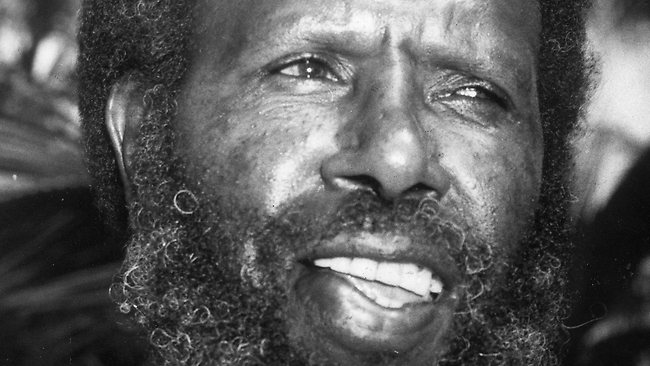

3Eddie Koiki Mabo

In 1936, Eddie Mabo was born on Mer Island in the Torres Strait. He grew up immersed in the traditional Torres Islander culture until he left the island at 16 years old. In 1959, he and his wife Bonita settled in the Queensland city of Townsville, where they raised 10 children. Eddie wanted his kids to have a good, standard education, but he also wanted them (and all native Australians) to learn about their own heritage. At his children’s school, their culture was ignored, and they were forbidden to use their traditional language on the playground. So in 1973, Eddie established the Black Community School in Townsville. Teaching grades one through seven, it was the first school in Australia with a curriculum that included indigenous history and culture. Eddie had another ambition for himself, his wife, and their children. He wanted to make sure that they could live on his family’s land on Mer Island. He was shocked when he learned that he had no claim to his childhood home because it, and all native land, actually belonged to the government. In 1982, Eddie launched Mabo v. Queensland. His lawsuit challenged terra nullius, the government doctrine that Australia was unoccupied at the time of colonization so the British Crown had been entitled to take ownership of all its territory. Eddie was fighting to overturn centuries of government privilege, which wasn’t an easy task. Gail Mabo, his middle daughter, says that her father taught her to “keep fighting the fight. If you give up, they win. So don’t give up.” She watched him practice what he preached for 10 years, as he located witnesses and gathered evidence. He worked on his lawsuit until he died in January 1992. Only five months after Eddie’s death, the High Court overturned terra nullius and upheld the land-owning rights of all indigenous Australians. Known simply as “Mabo,” it’s been called the decision that changed Australia. For the first time, the government acknowledged the thousands of years of native Australian history, their culture, and their rights to their land.

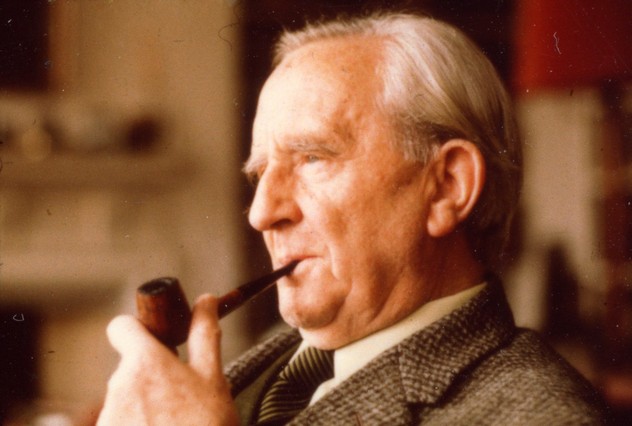

2J.R.R. Tolkien

Lots of dads tell their children bedtime stories, but Oxford professor John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was a master of the art. His lucky kids—John, Michael, Christopher, and Priscilla—drifted off to rambling tales that included goblins, elves, dragons, and wizards. A new character was introduced after Tolkien was grading his students’ test papers and realized he’d written something on a blank page in a student’s exam book: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” The professor had no idea what hobbits looked like or how they lived; those details evolved in his bedtime stories about Bilbo Baggins, a hobbit who loved to eat good meals, smoke his pipe, and whose comfortable hobbit hole had everything he needed—except adventure. Tolkien and his children had a favorite bedtime book, The Marvelous Land of the Snergs by E. A. Wyke-Smith. Snergs were a small, sturdy people living in a hidden kingdom, and they influenced Tolkien’s vision of Bilbo. Hobbit tales were also influenced by the children, especially Christopher, who was a stickler for consistency and complained if dad accidentally changed Bilbo’s front door from blue to green. Eventually, a publisher expressed interest in Bilbo’s adventures, and Tolkien polished up the story. The Hobbit was published in 1937 and was so popular that the publisher asked for a sequel. Christopher (by then grown up) became his father’s assistant on the sequel, The Lord of the Rings, which took over a decade to complete. Christopher helped with typing and drew maps for the book. Most importantly, he was still an important audience for hobbit tales. Even during World War II, when Christopher was serving in the Royal Air Force, Tolkien mailed him the newly written chapters. Finally published in 1954, The Lord of the Rings became the most popular fantasy fiction of the 20th century. Those continuing adventures of hobbits made Tolkien one of the most influential authors in the world.

1William Jackson Smart

In 1865, 23-year-old William Jackson Smart was a Union Army veteran of the Civil War, an Arkansas farmer, and a just-married man. He and his wife Elizabeth raised five children together, but Elizabeth died in 1878, making William a single father. Several years later, William married Ellen Billingsley, a widow with three children. They raised their combined families together. In 1882, with the birth of their daughter Sonora, they began adding to their brood with children of their own. Over the next few years, the couple had three sons. (That’s 12 kids, if you’re counting.) When the Arkansas farm couldn’t support his big family, William moved them to a farm near Spokane, Washington where he could make a better living. Two more boys were born in Washington, and though the older children were always growing up and moving on, William and Ellen Smart still made Carol and Mike Brady look like empty nesters. Then, in 1898, Ellen died. The oldest child still at home, 16-year-old Sonora, watched with admiration as her grief-stricken dad kept the family together. She would later say he became “both father and mother” to the six kids still under his roof. In 1909, while listening to a Mother’s Day sermon at a Spokane church, Sonora decided that it was time to honor fathers like her own self-sacrificing dad. Sonora was an energetic organizer, and on June 19, 1910, Washington State celebrated its first official statewide Father’s Day. Unfortunately, when it came to going national, Sonora ran into a 52-year snag. Many men, including Congressmen, weren’t interested in making Father’s Day a national holiday. Some saw it as too sentimental. Others figured the day would become too commercial, with dads paying the bills for their own presents. The determined Sonora kept up her campaign. As Congress squabbled about making Father’s Day official, more people (encouraged by retailers, of course) were already celebrating it on the third Sunday in June. Finally, in 1972, when Sonora was 90 years old, President Nixon declared Father’s Day a national holiday, and today it’s celebrated around the world. Sue Steiner is a frazzled mom and the author of Uncle John Presents Mom’s Bathtub Reader. She’s also the author of the upcoming book Amazing Moms Who Changed The World. You can reach her here.