10William Buckland’s Guano Message

The name William Buckland might not resonate with a lot of people these days, but he was one of the most prominent paleontologists of the 19th century. He was also the Dean of Westminster for a while. Even so, nowadays he is more famous for his voracious appetite—he ate all the different species of animals he could get his hands on. A renowned apocryphal story about him says that he ate the preserved heart of Louis XIV, the Sun King, when he saw it on display. Surely, someone this eccentric as an adult would be quite mischievous in his younger days. While a student at Oxford, Buckland came up with a rather clever application for guano, or bat droppings. Back then, guano was still relatively new to the UK. People knew that it worked very well as a fertilizer, but the practice was still deemed rather vulgar. For his prank, Buckland somehow managed to get a hold of several buckets of guano and proceeded to spread it on the university lawn. He didn’t, however, spread it evenly. Instead, he used it to form the letters G-U-A-N-O. The faculty removed it but not soon enough. The nutrient-rich guano had fertilized the soil. From then on, grass always grew faster and thicker in those areas, making the word clearly visible in grass graffiti to anyone seeing it from above.

9Benjamin Franklin’s Satirical Pseudonym

We’ve already mentioned that Benjamin Franklin regularly courted outrage and controversy, so it shouldn’t be surprising to find out that he also liked to pull a prank or two. In his teenage years, he worked at a newspaper called The New-England Courant, founded and run by his brother. Initially, Ben wanted to publish some letters as himself, but his older brother James said no. This left Franklin with only one sensible alternative—impersonate a middle-aged widow. Her name was Silence Dogood. She was the widow of a minister, an “enemy to vice and a friend to virtue.” Over the course of six months in 1722, Franklin wrote 14 letters under her name. He made sure to change the handwriting and left the letters at the door of the print shop. They proved to be quite popular, and the widow Dogood even started receiving marriage proposals from readers. Nobody ever caught on to young Ben’s actions, but he grew tired of the ruse and eventually came clean to his brother.

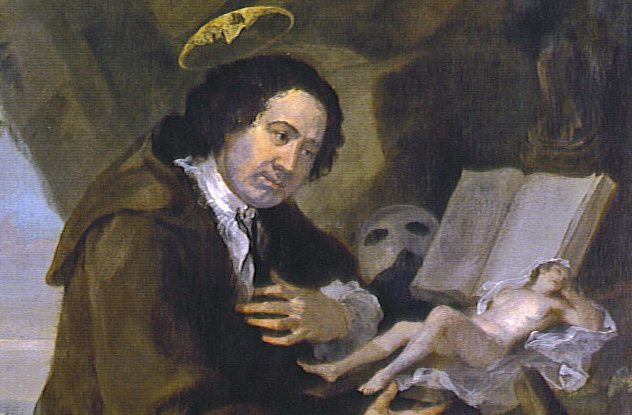

8Francis Dashwood’s Diplomatic Faux-Pas

Francis Dashwood certainly managed to garner quite a reputation for himself. In his youth, he achieved this by founding the Hellfire Club, which became infamous for hosting debauched and lavish parties filled with wine, women, and some mild blasphemy. He wasn’t one to shy away from an opportunity to mock the Church, which is probably what led to rumors of him being a Satanist. On one occasion, he commissioned a portrait of himself, pictured above, parodying a famous painting of St. Francis of Assisi. However, instead of reading the Bible, Dashwood was staring at a naked woman and an erotic book. As a little Easter egg, the face of his friend Lord Sandwich was hidden in his halo. On another occasion, Dashwood published an abridged version of the Book of Common Prayer so that the pious would not have to endure long speeches in cold churches. This book was cowritten with a fellow prankster, the aforementioned Benjamin Franklin. However, during his travels, Dashwood’s behavior got him in trouble. While staying at the Russian Court, Francis thought it would be funny to turn up at a social event dressed as Charles XII, King of Sweden. Sweden was, back then, Russia’s mortal enemy thanks to the Great Northern War, and he apparently did this in an attempt to impress Tsarina Anna. Whether or not this actually worked remains unknown, but rumors of an affair between the two soon started popping up.

7Bob Knight’s Yugoslav Superstar

As far as college basketball coaches go, Bobby Knight is considered among the very best. As a result of this, he enjoyed a three-decade career coaching the Indiana Hoosiers. However, all that time didn’t go by without controversy. Knight didn’t like to engage with the press. In 1992, he played a prank targeting the press and so-called sports insiders. Ivan Renko was supposedly a new recruit—a 203-centimeter (6’8”) superstar out of Yugoslavia. Knight talked on TV about how excited he was that Renko decided to sign with Indiana. In reality, Renko didn’t exist, but this didn’t stop the press and experts from responding. They didn’t want to look like they got caught off-guard, so several of them began talking extensively about this new prospect. Some claimed that he was overrated, while others said that he was really good. Some even claimed to have seen footage of Renko in action. What made things even more embarrassing is that these insiders really should have known better. For starters, Knight would not have been allowed to talk about Renko until he signed a letter of intent, according to NCAA rules. Furthermore, Indiana lacked the open scholarship to recruit Renko, even if he were real.

6Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Explosive Exploits

Percy Bysshe Shelley was one of the great Romantic poets. He was also part of a famous circle of poets and writers, including Lord Byron and his own wife, Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Before all this, though, Shelley endured a grueling life at school at Eton. Being fascinated with science, Shelley refused to engage in sports and other activities preferred by his schoolmates, and this made him a frequent victim of abuse by older students. Even worse, the headmasters (who also didn’t like Shelley) would often overlook his suffering. Shelley preferred to experiment with elements rather more dangerous than sports—fire and electricity. On one occasion, Shelley almost electrocuted his tutor by connecting a charged Leyden jar to the doorknob of his room. He also indulged his pyromania by setting fire to the old trees on campus. One time, he added some gunpowder to the mix and blew up a tree, almost blowing himself up as well, according to eyewitness accounts. Such actions almost got him expelled on more than one occasion, but for his father’s interference. Even so, the exploded tree became part of Eton legend. His fellow students even composed a poem about it. According to the story, the stump of the willow is still there today, located in the “northernmost point of South Meadow.”

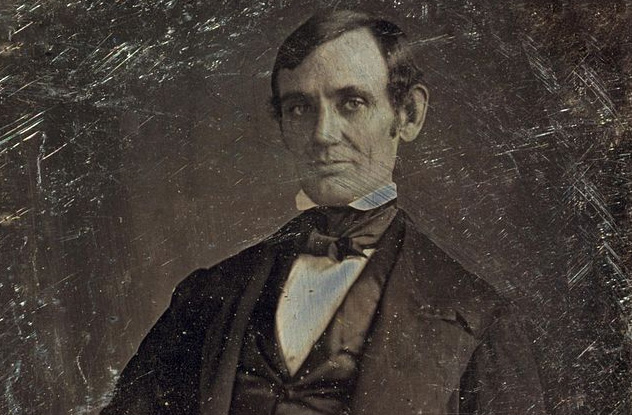

5Abraham Lincoln’s Jovial Nature

We’ve already talked about the many US presidents who enjoyed pulling pranks. Abraham Lincoln, in particular, liked to prank his political opponents, but sometimes, the people closest to him became the butt of his jokes. One likely apocryphal story tells of his exploits as a teenager targeting his stepmother, Sarah Bush Lincoln. Sarah often teased young Abe about his lanky, tall frame, claiming that he’d better “keep his head clean, or she’d have to scrub her whitewashed ceiling.” One day, Abe watched two small boys play barefoot in the mud, and he got an idea. He invited the boys inside. One by one, he lifted them up, flipped them upside down and had them walk on his stepmother’s beloved ceiling. According to the story, Sarah Bush took it in good humor, although Abe did have to whitewash the ceiling afterward. The city of Monticello, Illinois was also witness to another one of Lincoln’s supposed pranks, one that almost set the Tenbrook Hotel on fire. While staying at the hotel, Abe scared a few kids by advising them to heat up an inflated pig bladder (predecessor to the modern balloon) in the hotel fireplace. The bladder soon popped, startling everyone in the hotel and also spreading hot coals and embers all over the room. Lincoln offered to sweep up the debris, but in doing so, he set the broom on fire.

4Joseph Mulhattan’s Hemp-Picking Monkeys

Joseph Mulhattan was a salesman by trade, but his true passion was deceiving the newspapers with outlandish stories. At various times, he was called the most famous liar in the United States, the author of more hoaxes than any other man living, the “Prince of Liars,” and the “liar-laureate of the world.” He liked to describe his work as “novelistic journalism.” He never made money from his pranks, apart from the large salary he enjoyed as a salesman since everyone wanted to do business with him and hear his latest stories. Mulhattan submitted numerous hoaxes. Many were only published by small, local newspapers and are now lost forever. Among his most notorious pranks, though, is a tale of a meteorite landing in Texas, a little girl being carried away by balloons, and George Washington’s body found petrified and put on display. Arguably, his most successful hoax came when he reported of a Kentucky farmer who successfully trained monkeys to work his hemp fields. The story was picked up by the Kentucky Register, which published it along with an editorial about how this could affect labor in the country. Soon enough, prominent newspapers like The Times and the New York Times were also reporting on the story, berating the farmer for endangering the livelihood of human laborers.

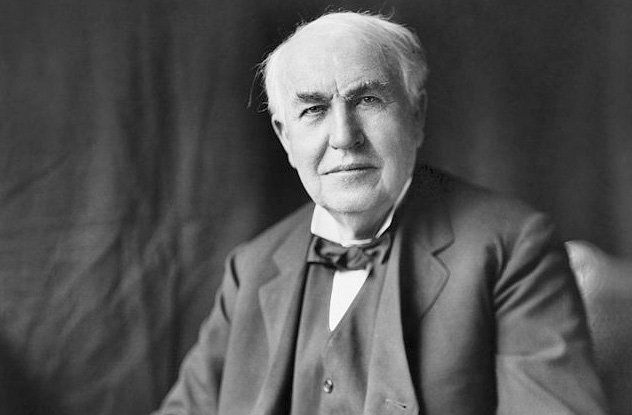

3Thomas Edison’s Food Creator

At the height of Thomas Edison’s success, newspapers regularly published accounts of his most recent inventions. There came a point where people seemed willing to believe that Edison could invent almost anything. One journalist for the New York Daily Graphic put this idea to the test. On April 1, 1878, he published an account of Edison’s latest invention. It was called the “Food Creator,” and it created food out of nothing but air, water, and earth. It was hailed as the invention that would feed the human race, and it was believed not only by readers but by other newspapers as well. The Commercial Advertiser, in particular, published an editorial exalting Edison’s genius, an editorial later reprinted by the Daily Graphic with the gloating subtitle of “They Bite!” The publishing date on April 1 should’ve tipped people off. Furthermore, the original story ended with the narrator being woken by a train conductor, indicating that the entire event was a dream. Nevertheless, Edison received inquiries about the food creator. Very amused with the prank, he proclaimed it the “most ingenious hoax I have ever seen” and played along with reporters from other newspapers.

2Harvey Stromberg’s MOMA Exhibition

Most artists would agree that having their work exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is a highlight in their careers. It certainly did a lot for the career of artist Harvey Stromberg in the 1970s. But what made his exhibition even more impressive was that nobody at MOMA knew anything about it. For several weeks, Stromberg pretended to be an art student, spending hours each day with a notepad inside the museum. It looked like he was admiring the art pieces, but he was actually taking detailed notes and photographs of every item inside the museum except the art pieces. These included air vents, bricks, light switches, floor tiles, and keyholes. He used his notes to create and print actual-size stickers of all these items. He called them “photo-sculptures” or trompe-l’oeil. The 2-D imagery created the illusion of three dimensions. The next step was to place the stickers over their real-life counterparts. Stromberg did this one sticker at a time so he wouldn’t get caught. Museum staff would occasionally find them (especially the floor stickers that came off after the floors were buffed), but Stromberg came back and replaced them. Some stickers stayed on for two years until Stromberg decided to have an “official” opening for his project.

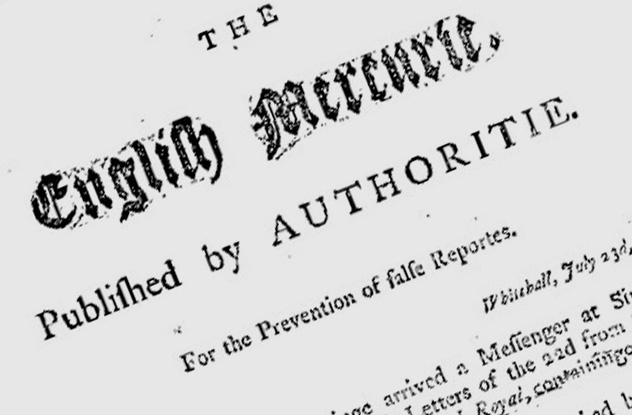

1The Earl Of Hardwicke’s Newspaper Hoax

Very few pranks have the long-lasting effect of this particular hoax from the 18th century, which is still occasionally mistaken as fact even today. It was perpetrated by Philip Yorke, Second Earl of Hardwicke and future Fellow of the Royal Society, along with a friend of his and noted historian Thomas Birch. Together, they created the English Mercurie, a publication that for decades would be thought of as the first English newspaper in history. They did this in the 18th century, well after English newspapers were being published. However, the English Mercurie was dated July 23, 1588. Supposedly, it was an Elizabethan-era publication that detailed the fight between the English and the Spanish Armada. Five issues were created (three in print and two manuscripts) and were convincing enough to fool everyone into thinking they were newspapers almost 200 years old. A lot of the blame goes to George Chalmers, a Scottish historian. He was completely convinced of the authenticity of the English Mercurie and proclaimed it to be the first newspaper of its kind in several publications, including one of his most successful works, the 1794 biography of Thomas Ruddiman. It would take 45 more years after Chalmers’s assertions before someone would finally catch on to the hoax and name the long-dead earl as its perpetrator. Radu is a history/science buff with an encyclopedic knowledge of The Simpsons and not much else. He also tweets.