While the majority of the world remained hands-off, there were villages, cities, and countries that protected their at-risk neighbors and welcomed those seeking asylum. In these places, refugees were allowed to worship freely and conduct business. Most importantly, they were saved from being sent to concentration camps, where they would have endured starvation, brutality, and, often, death. Here are ten places where refugees found respite from the horrors of the Holocaust.

10 Sosua

By 1938, Hitler’s regime had driven hundreds of thousands of Jews from their homes and countries. President Roosevelt requested an international conference to discuss options for handling the vast number of refugees. Representatives from 32 countries met in Evian, France, for nine days. Nearly every delegate spoke of sympathy for the refugees. However, they did not offer assistance beyond filling their current immigration quotas or permitting nominal numbers of additional visas. This was during the Great Depression, and a lack of resources and funds was commonly given as an excuse for declining to help. The only country to make a significant offer of assistance was the Dominican Republic. Dictator Rafael Trujillo pledged to accept up to 100,000 refugees. Trujillo’s reasons for doing so were not entirely altruistic. It has been said that he only agreed to accept refugees in order to receive the associated financial aid. In addition, Trujillo was seeking to improve his international reputation after slaughtering thousands of Haitians. Finally, Trujillo planned to “whiten” up his country by encouraging black natives to marry light-skinned refugees. Regardless of Trujillo’s motives, Sosua became home to hundreds of people with nowhere to go. Transportation from Europe to the Caribbean was difficult during the war, so only about 800 refugees actually arrived in the Dominican Republic. The majority of them were settled in the undeveloped coastal town of Sosua. Each refugee received a small parcel of land and some livestock. For many, life in Sosua was an adjustment—and not just because they were in a new country. Former businessmen and doctors had to learn how to make a living in agriculture. But they learned and adapted to their new life. Sosua became a community, with a synagogue for worship and a school for the children.[1]

9 Bolivia

More than 20,000 Jewish refugees fled to Bolivia between 1938 and 1941. Mauricio Hochschild was largely responsible for the number of visas issued to Jews fleeing the Holocaust. Hochschild was a tin mining tycoon with a reputation for exploiting his workers and evading taxes. But before moving to Bolivia, Hochschild had once been a Jew living in Germany. When he learned what was happening in his former country, he sought to save as many Jewish refugees as he could. Hochschild’s success as an entrepreneur had given him political ties. He had a friendship with German Busch, Bolivia’s military president at the time. Hochschild convinced Busch that admitting Jews would be a good way to grow Bolivia’s labor force. Hochschild himself covered the costs of travel for more than 9,000 refugees. The Jews arrived by boat in Chile and then rode a train to La Paz, Bolivia. They were arriving so regularly that the train became known as the “Jewish Express.” Hochschild provided the refugees with housing and set them up with jobs in his workforce. He also financially supported a school for the Jewish children. After Hochschild’s role in helping the refugees was discovered, he became known as the “Bolivian Schindler.”[2]

8 Haiti

A little-known place that took in refugees during the Holocaust is the small nation of Haiti. At the Evian conference, Haiti’s diplomat offered to accept up to 50,000 Jewish refugees. The proposal was rejected, but Haitian diplomats throughout Europe issued as many visas as they could. An estimated 300 Jews were able to make the long journey to the Caribbean nation, and they were welcomed upon their arrival. The Haitian people had experienced their own share of persecution and suffering at the hands of others and were sympathetic toward the Jewish refugees.[3] Some of the Jewish refugees who arrived in Haiti remained there and made it their home. But for many, it was a Nazi-free place for them to await the approval of their US immigration papers. Their stay in Haiti was brief, but they were incredibly grateful to the country and its people for giving them a safe stopover on their journey.

7 Shanghai

Prior to and during World War II, many countries closed their borders to the thousands of refugees fleeing their homes. One exception was Shanghai, where foreigners could enter without visas or even passports. Approximately 17,000 Jewish refugees made their way to the port city. Shanghai was far from Utopia. It was overcrowded, with people living on top of one another. Refugees with financial means housed themselves in run-down buildings, while the destitute were put up in barracks. But the European Jews persisted, doing whatever they could to make ends meet. Some found success running bakeries, cafes, or shops, while others worked as builders, teachers, or doctors.[4] When Shanghai became occupied by the Japanese, life changed again for the refugees. The Jews were confined to a designated area in the Hongkou district, which became known as the Shanghai Ghetto. Clothing and food were in short supply, and disease and fear ran rampant. Yet social events and religious services still took place, and children were allowed day passes out of the ghetto to continue their schooling. Despite the hardships faced by the Shanghai refugees, they fared far better than they would have in Europe. The Japanese oppressed the Jews, but they did not seek to systematically exterminate them. They ignored the “final solution” proposed by the Nazis, which consisted of gathering the Shanghai Jews and either sending them to gas chambers or loading them onto barges in which they would drift off and die of starvation. The Shanghai Jews did not discover the horrors that took place in Europe until after the war ended. The majority of them had survived, and when they realized the slaughter they had escaped, they were simultaneously filled with relief and guilt.

6 Sweden

Sweden remained officially neutral during World War II, but they appeared to favor the Germans early on. German troops were granted passage through Sweden, and the nation provided the Germans with iron ore during the war. Like many countries, Sweden severely restricted the immigration of Jewish refugees. But after the truth of what the Nazis were doing came to light, Sweden’s stance shifted. The country opened its borders and became a sanctuary for thousands of refugees. Denmark was occupied by Germany in 1940, but the Danish government negotiated to retain a certain amount of power and protect their Jewish population. This arrangement held until 1943, when increasing unrest from the Danish resistance caused Germany to threaten the Danish government. The Danish government resigned in protest. With the Danish Jews no longer protected by their government, Hitler ordered all of them to be sent to concentration camps. A German diplomat alerted a leader in the Danish resistance of the impending deportation. Throughout the country, neighbors and strangers alike helped hustle more than 7,500 Jews to the coast. From there, they were shuttled across the narrow channel and into Sweden. The refugees remained there safely for the remaining 19 months that Germany occupied Denmark.[5] In addition to granting asylum to nearly the entire population of Danish Jews, Sweden also took in approximately 900 Norwegian Jews facing deportation. Sweden’s own Jewish population of 7,000 were protected by the country’s neutrality.

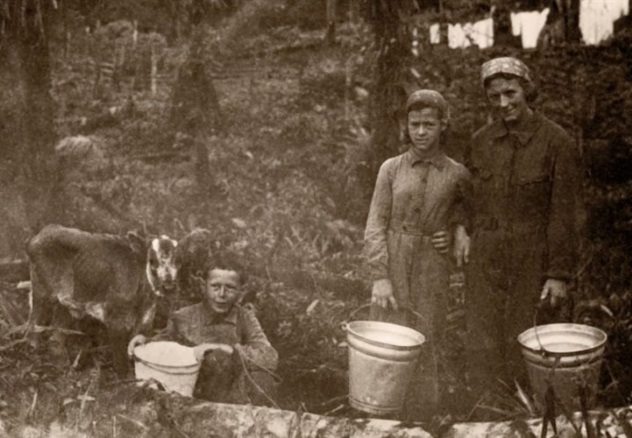

5 Ecuador

Prior to Hitler’s rise and World War II, Ecuador had a Jewish population of fewer than 20 people. Between 1933 and 1943, 2,700 Jews found refuge in the South American nation.[6] In Ecuador, the refugees were expected to work in agriculture. For accountants and dentists, this lifestyle was new and did not prove to be a success. Many Jews struggled to find a new way to make a living, attempting various crafts and trades. Sixty families were settled on established chicken farms, but they all ultimately failed. Furniture-building was a popular source of income, and the refugees were the first to introduce steel and iron pieces to the Ecuadorian market. Adapting to a new country came with many challenges, but some of the refugees thrived, starting businesses that still exist today.

4 Zakynthos

Zakynthos is a Greek island located in the Ionian Sea. During the Holocaust, it had a population of 275 Jews. They were protected by Chrysostomos Demetriou, the bishop of Zakynthos, and Loukas Karrer, the mayor. German commander Berenz and his forces arrived on the island of Zakynthos in October 1943. Berenz met with Mayor Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos and informed them that all Jews living on the island must adhere to a strict curfew and identify themselves with a sign on their door. The bishop argued that the Jews were a part of the island’s community and should not be mistreated. Berenz told the two men that regardless, the Jews will eventually be deported. The people of Zakynthos, including the mayor and bishop, were aware of the death camps and what deportation ultimately led to. Mayor Karrer warned the Jews, who were then sheltered in Christian homes throughout the island. Berenz summoned Mayor Karrer again in October 1944. This time, the German commander ordered Mayor Karrer to provide a list of all Jews in Zakynthos within 24 hours, under threat of his own life. Mayor Karrer conferred with Bishop Chrysostomos. The next day, the two men presented Berenz with a list that contained merely their own names. The bishop also gave Berenz a letter addressed to Hitler, stating that the Jews of Zakynthos were under his protection. Berenz sent both documents to the German High Command in Berlin and requested guidance on how to handle the situation. The order to deport the Zakynthos Jews was revoked, and the German forces left the island. All 275 Zakynthos Jews survived.[7]

3 Philippines

Between 1937 and 1941, approximately 1,200 Jews fled to the Philippines. Many came from Austria and Germany, pushed out of their countries by increasingly harsh anti-Semitic policies. At the time, the nation of islands was the Commonwealth of the Philippines. The Asian country was in a transitory period from American rule to independence, and foreign policy was still controlled by the United States. Manuel Quezon, the commonwealth president, sought to welcome as many Jewish refugees as possible. The US would not issue visas to anyone in need of financial assistance, so Quezon planned to bring 10,000 skilled refugees to his shores. He arranged for doctors, accountants, a rabbi, and even a conductor to enter the country. The European Jews experienced culture shock in the Philippines. The weather, food, and language were all very different than what they were accustomed to. But the Filipinos were welcoming, and the refugees were able to live freely. The stream of refugees was interrupted when the Japanese invaded in 1941. Those who had been safe were suddenly on the front lines of the war. But the Japanese forces did not share Hitler’s agenda of exterminating the Jews. Instead, those with German passports were seen as allies. The European Jews were left alone, while Filipinos and Americans were imprisoned. Life was still hard for the refugees, as the islands became battlefields. Bombs dropped regularly, land mines were abundant, and the body count continued to rise. Yet many Jews survived the war and remained grateful that their time in the Philippines kept them out of the concentration camps in Europe.[8]

2 Llanwrtyd Wells

During the Holocaust, more than 130 Czechoslovakian Jewish children were kept happy and safe in a tiny town in Wales. The residents of Llanwrtyd Wells were unaccustomed to foreigners. But when the children arrived, transported by one of Nicholas Winton’s trains, the town welcomed them with open arms. A local hotel became a Czechoslovakian boarding school for the children. Most of them were unaware of the horrors their parents faced in their home country. The kids lived relatively normal lives, studying in school and playing games on the playground. Since the Jewish children were without their parents, the local residents cared for and looked after them. One shop owner drove the kids to sporting events on the weekends. One of the little girls, now grown, remembers the time as one of the happiest in her life. After the war ended, many of the Czech children learned that their parents had perished. The kids left the small town to either reunite with surviving relatives or move on with their lives. But as adults, they returned to Llanwrtyd Wells to pay tribute to the town that sheltered them during the Holocaust.[9]

1 Le Chambon-Sur-Lignon

Many individual heroic efforts to help refugees were made during the Holocaust. But in the mountains of Southern France, an entire region worked together to protect those fleeing the Nazis. Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and its surrounding villages sheltered thousands of refugees during the Holocaust. An estimated 3,500 of them were Jews, mainly children, while the rest were Spanish Republicans, anti-Nazi Germans, and members of the French resistance. The residents in the Protestant region were strongly opposed to Hitler’s message of anti-Semitism. Their people had suffered persecution from the Catholic Church, and they did not wish to see another group of people being punished for their culture. A local pastor knew a Quaker who was able to negotiate the release of Jewish children from internment camps in Southern France. When the Quaker mentioned that the children had nowhere to go, the pastor immediately offered to find homes for them in Le Chambon. The town and surrounding communities all pitched in to welcome the Jewish children into their homes and provide them with food, clothing, and forged papers. Additional refugees made their own way to the region after word of mouth began to spread that Le Chambon was a safe place for Jews and anyone fleeing the Nazis. Local residents hid the refugees in plain sight, helping them blend in and appear as if they belonged. Some refugees were sheltered during the entire war in the remote villages, while others were taken to the Swiss border and smuggled out of the country. Thanks to the collective efforts of the region, an estimated 5,000 refugees survived.[10]