10Michihiko Hachiya, Hiroshima ResidentAugust 6, 1945

We started out, but after 20 or 30 steps, I had to stop. My breath became short, my heart pounded, and my legs gave way under me. An overpowering thirst seized me, and I begged Yaeko-san to find me some water. But there was no water to be found. After a little, my strength somewhat returned, and we were able to go on. I was still naked, and although I did not feel the least bit of shame, I was disturbed to realize that modesty had deserted me . . . Our progress towards the hospital was interminably slow, until finally, my legs, stiff from drying blood, refused to carry me farther. The strength, even the will, to go on deserted me, so I told my wife, who was almost as badly hurt as I, to go on alone. This she objected to, but there was no choice. She had to go ahead and try to find someone to come back for me. On August 6, 1945, an atomic bomb detonated directly over central Hiroshima, immediately killing around a quarter of the city’s population and exposing the remainder to dangerous radiation levels. When the bomb hit, a hospital worker named Michihiko Hachiya was lying down in his home, around 1.5 kilometers (1 mi) from the center of the explosion. His incredible diary, published in 1955, recounts his experiences that day. The above passage describes Michihiko’s short journey to the hospital just minutes after the detonation. The sheer force of the blast had ripped the clothes from his body and his entire right side was badly cut and burned. The “overpowering thirst” that Michihiko describes is a direct effect of losing body fluid from severe burns. Both Michihiko and his wife were lucky to survive. The area of the city they inhabited saw a fatality rate of 27 percent. Just 0.8 kilometers (0.5 mi) closer to the center of the explosion, the fatality rate was 86 percent. While most historians agree that the atomic bombings of Japan were necessary to accelerate the Japanese surrender, eyewitness accounts like Michihiko’s give a clear image as to why nuclear weapons have never been used again.

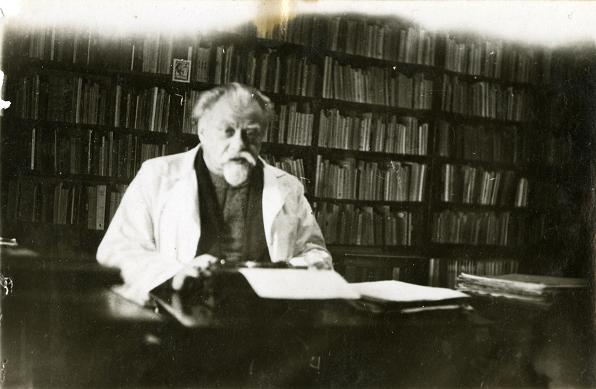

9Zygmunt Klukowski, Polish DoctorOctober 21, 1942

From early morning until late at night, we witnessed indescribable events. Armed SS soldiers, gendarmes, and “blue police” ran through the city looking for Jews. Jews were assembled in the marketplace. The Jews were taken from their houses, barns, cellars, attics, and other hiding places. Pistol and gunshots were heard throughout the entire day. Sometimes hand grenades were thrown into the cellars. Jews were beaten and kicked; it made no difference whether they were men, women, or small children. All Jews will be shot. Between 400 and 500 have been killed. Poles were forced to begin digging graves in the Jewish cemetery. From information I received, approximately 2,000 people are in hiding. The arrested Jews were loaded into a train at the railroad station to be moved to an unknown location. It was a terrifying day. I cannot describe everything that took place. You cannot imagine the barbarism of the Germans. I am completely broken and cannot seem to find myself. On January 20, 1942, 15 senior Nazi officials held a conference to discuss the implementation of a “Final Solution” to obliterate the Jewish people. It took another nine months for the genocide to reach the sleepy town of Szczebrzeszyn in southeast Poland. The above diary entry was written by Zygmunt Klukowski, the chief physician of Szczebrzeszyn’s small hospital. Klukowski was an enthusiastic diarist and noted everything that occurred in his village during the Nazi occupation. He took a great risk in doing so, knowing that the discovery of his chronicle would have marked him for death. This particularly harrowing entry documents the speed and ferocity with which Jews were rounded up in thousands of villages and towns throughout Eastern Europe. The following day, Klukowski noted that the German SS had already left the village, leaving the Polish military police in charge of locating any remaining Jews. Klukowski, who was devastated by his inability to do anything to help the injured, expressed disgust at how many of his fellow townsfolk took part in the violence against the Jews.

8Lena Mukhina, Leningrad ResidentJanuary 3, 1942

We are dying like flies here because of the hunger, but yesterday Stalin gave another dinner in Moscow in honor of [the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony] Eden. This is outrageous. They fill their bellies there, while we don’t even get a piece of bread. They play host at all sorts of brilliant receptions while we live like cavemen, like blind moles. To say that the Russian people had it rough during World War II would be a monumental understatement. Depending on the source, it’s estimated that between 7–20 million Russian civilians died as a direct result of the conflict. In Leningrad alone, as many as 750,000 civilians starved to death as the Germans placed the city under siege for over two years, from September 1941 to January 1944. The above diary entry was written by 17-year-old resident Lena Mukhina just a few months into the siege. As the blockade wore on, residents were reduced to eating rats, cats, earth, and glue. There were widespread reports of cannibalism. At the time the entry above was written, Lena was living with her aunt, who tragically died from hunger a month later. Lena managed to survive by concealing the death from the authorities, allowing her to continue using her aunt’s food card. In later entries, she begins to plot an escape to Moscow. Her diary ends suddenly on May 25, 1942, when she made a dangerous journey to safety across Lake Ladoga. Lena died in 1991, a few short months before the Soviet Union finally collapsed.

7Felix Landau, SS OfficerJuly 12, 1941

At 6:00 in the morning, I was suddenly awoken from a deep sleep. Report for an execution. Fine, so I’ll just play executioner and then gravedigger, why not. Isn’t it strange, you love battle and then have to shoot defenseless people. Twenty-three had to be shot, amongst them the two above-mentioned women. They are unbelievable. They even refused to accept a glass of water from us. I was detailed as a marksman and had to shoot any runaways. We drove one kilometer along the road out of town and then turned right into a wood. There were only six of us at that point, and we had to find a suitable spot to shoot and bury them. After a few minutes, we found a place. The death candidates assembled with shovels to dig their own graves. Two of them were weeping. The others certainly have incredible courage. What on earth is running through their minds during these moments? I think that each of them harbors a small hope that somehow he won’t be shot. The death candidates are organized into three shifts as there are not many shovels. Strange, I am completely unmoved. No pity, nothing. That’s the way it is, and then it’s all over. My heart beats just a little faster when involuntarily I recall the feelings and thoughts I had when I was in a similar situation. Felix Landau was a member of the feared German SS. For much of the war, he belonged to an Einsatzkommando, a mobile death squad charged with exterminating Jews, Romani gypsies, Polish intellectuals, and a number of other groups within Nazi-occupied territory. Landau operated throughout Poland and Ukraine, slaughtering his way from town to town. His remarkable diary details his appalling crimes, often in graphic detail. This entry, from July 1941, records his actions in the city of Drohobych in western Ukraine. The lack of emotion he feels during the killings is typical of SS officers who took part in mass executions. Landau was documented as being particularly brazen in his ill-treatment of Jews, randomly shooting at them from his window as they walked down the street. Following the war, Landau managed to evade capture until 1959, when he was put on trial and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was released for “good behavior” in 1971 and died in 1983.

6Leslie Skinner, British Army ChaplainAugust 4, 1944

On foot located brewed up tanks. Only ash and burnt metal in Birkett’s tank. Searched ash and found remains pelvic bones. At other tanks three bodies still inside. Unable to remove bodies after long struggle—nasty business—sick. The diary of Captain Leslie Skinner documents his experiences of the brutal conflict immediately following the D-Day landings. Skinner was not a combat soldier but a priest, assigned as an army chaplain to the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry tank regiment. The first chaplain to land on D-Day, he was badly wounded by a mortar shell but quickly returned to the front and stayed with the regiment throughout its campaign in northwest Europe. Known as “Padre Skinner,” his job was to provide spiritual comfort and perform last rites. A more harrowing part of the job involved recovering the bodies of the dead to give them a proper burial: Fearful job picking up bits and pieces and reassembling for identification and putting in blankets for burial. No infantry to help. Squadron Leader offered to lend me some men to help. Refused. Less men who live and fight in tanks have to do with this side of things the better. My job. This was more than normally sick making. Really ill—vomiting. Padre Skinner donated his diary to the Imperial War Museum in 1991. He died 10 years later at the age of 89.

5David Koker, Concentration Camp PrisonerFebruary 4, 1944

A slight, insignificant-looking little man, with a rather good-humored face. High peaked cap, mustache, and small spectacles. I think: If you wanted to trace back all the misery and horror to just one person, it would have to be him. Around him, a lot of fellows with weary faces. Very big, heavily dressed men, they swerve along whichever way he turns, like a swarm of flies, changing places among themselves (they don’t stand still for a moment) and moving like a single whole. It makes a fatally alarming impression. They look everywhere without finding anything to focus on. While Holocaust survivors have written a number of memoirs, only a few diaries have been recovered from the concentration camps. One was written by David Koker, a Dutch student of Jewish descent who was sent to Camp Vught in southern Holland in February 1943. David’s story has strong similarities with that of Anne Frank. He had lived in Amsterdam with his parents and younger brother until he was captured. Unlike Anne, however, David began his diary after he was captured. While most concentration camp prisoners would have been prevented from keeping a diary, David had befriended the camp clerk and his wife at Vught, meaning he was allowed extra privileges. The above entry is quite remarkable—it is a description of Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. Himmler visited Vught in February 1944, giving Koker an eyewitness view of the man responsible for persecuting his people. Later that month, a camp employee smuggled Koker’s diary to safety. Koker himself was moved between camps as the Allies retook much of occupied Europe. He died in 1945, while being transported to the notorious Dachau concentration camp.

4Nella Last, Resident Of LondonApril 15, 1941

Midnight: Sounds of bombs and waves of planes going over to either the Clyde or Northern Ireland, machine gunning. All making an inferno of sound and the crump of bombs falling in the centre of the town is dreadful. 2am: I wonder if anything will be left of the centre of the town, there are such dreadful crumps. I cannot relax or sit down for every 15 minutes or so we run for cover while shrapnel pours on the roof and bombs dropped somewhere make the doors and windows shake and rattle. 4am: The devil planes must be coming back now – a hundred must have passed over tonight. I think I’d like to cry or swear or something. In September 1939, Nella Last began a diary that was to continue for nearly 30 years. She was a volunteer with the Mass Observation Archive, set up in 1937 in Britain. The project wanted to record the views of ordinary British people and recruited volunteers to record a day-to-day account of their lives. These archives now give a unique insight into the lives of British civilians who found themselves going through a period when their country was at war. Nella Last was a housewife, married to a shop-fitter and joiner. Their younger son, Cliff, was in the Army, and the older son, Arthur, was a tax inspector and therefore exempted from conscription in the war. Both were now living away from home. The Lasts lived in Barrow-in-Furness—a shipbuilding town—that became a target for German bombing during the Blitz. This was a period when families were separated and sometimes coping with the loss of a family member. Cities were being bombed, and housewives such as Nella had to find new ingenious ways to keep their homes together. This remarkable account clearly depicts what it was like for ordinary families living through World War II. The diaries were published in 1981.

3“Ginger,” Resident Of Pearl HarborDecember 7, 1941

I was awakened at eight o’clock in the morning by an explosion from Pearl Harbor. I got up, thinking something exciting was probably going on over there. Little did I know! When I reached the kitchen, the whole family, excluding Pop, was looking over at the Navy Yard. It was being consumed by black smoke and more terrific explosions . . . Then I became extremely worried, as did we all. Mom and I went out on the front porch to get a better look, and three planes went zooming over our heads so close we could have touched them. They had red circles on their wings. Then we caught on! About that time, bombs started dropping all over Hickam. We stayed at the windows, not knowing what else to do, and watched the fireworks. It was just like the newsreels of Europe, only worse. We saw a bunch of soldiers come running full tilt towards us from the barracks, and just then a whole line of bombs fell behind them, knocking them all to the ground. We were deluged in a cloud of dust and had to run around closing all the windows. In the meantime, a bunch of soldiers had come into our garage to hide. They were entirely taken by surprise and most of them didn’t even have a gun or anything. The bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces in December 1941 effectively turned two existing regional conflicts in Europe and China into a World War. Aimed at the US naval base on the south coast of Hawaii’s Oahu island, the surprise attack left 2,403 Americans dead and was the catalyst for the United States to enter the war. The area surrounding Pearl Harbor was not restricted to servicemen but was inhabited by their families and local islanders. The diary entry above was written by a 17-year-old high school senior known as “Ginger” (her full name was not published along with the diary). Ginger lived at Hickam Field, on the eastern edge of the Pearl Harbor base. The diary demonstrates the shock the attacks caused. The Japanese had not yet declared war when the first bombs were dropped, which explains why the soldiers in Ginger’s account were so unprepared. The attack lasted only 90 minutes but destroyed a significant area of the base.

2Wilhelm Hoffman, German SoldierJuly 29, 1942

The company commander says the Russian troops are completely broken and cannot hold out any longer. To reach the Volga and take Stalingrad is not so difficult for us. The Fuhrer knows where the Russians’ weak point is. Victory is not far away. The most vital and bloodiest battles of World War II were fought on the Eastern Front. A telling statistic reveals that for every German that died on the Western Front, another nine died in the East. And the deadliest battle of the entire war was at Stalingrad, where a five-month bloodbath turned the tide in favor of the Soviet Union. The above diary entry comes from Wilhelm Hoffman, a soldier in the 94th Infantry Division of the German Sixth Army. Hoffman’s diary is an amazing insight into the attitude of ordinary German soldiers before and during the battle of Stalingrad. The entry was written at the end of July, a month before Stalingrad. Up to then, the German army had seen victory after victory, and Hoffman felt confident they could conquer Stalingrad and then the rest of Russia. Of course, it didn’t happen that way. Against all odds, the city’s defenders clung on, staging a brutal building-to-building fight while the Red Army prepared its counterattack. By December, it was the Germans who were surrounded. By that point, Hoffman’s diary had become pessimistic about the chance of victory. The entry from December 26, 1942, stands in stark contrast to his attitude during the summer: The horses have already been eaten. I would eat a cat; they say its meat is also tasty. The soldiers look like corpses or lunatics, looking for something to put in their mouths. They no longer take cover from Russian shells; they haven’t the strength to walk, run away and hide. A curse on this war! Hoffman would eventually die at Stalingrad, although it is not known precisely how or when this happened.

1Hayashi Ichizo, Japanese Kamikaze PilotMarch 21, 1945

To be honest, I cannot say that the wish to die for the emperor is genuine, coming from my heart. However, it is decided for me that I die for the emperor. I shall not be afraid of the moment of my death. But I am afraid of how the fear of death will perturb my life . . . Even for a short life, there are many memories. For someone who had a good life, it is very difficult to part with it. But I reached a point of no return. I must plunge into an enemy vessel. As the preparation for the takeoff nears, I feel a heavy pressure on me. I don’t think I can stare at death . . . I tried my best to escape in vain. So, now that I don’t have a choice, I must go valiantly. In the popular imagination, Japanese kamikaze pilots are fanatical imperialists eager to sacrifice themselves for their country. While this may have been true in some cases, other pilots had a very different story to tell. One such story was that of a Japanese student named Hayashi Ichizo, who was drafted in 1943 at the age of 21. In February 1945, he was assigned to serve as a suicide pilot. Just a month earlier, he had started keeping a diary. Like many students, Hayashi entered the army untrained and unsure about Japan’s role in the war. Although his family was opposed to the conflict, he had no way to escape the draft. Toward the end of the war, many students were chosen to be “Tokkotai” (suicide) pilots. The vast majority were under the age of 25. The youngest recorded pilot, Yukio Araki (pictured above holding his puppy), was just 17. Officially, all the pilots had volunteered, but many were essentially forced into the role. Hayashi’s incredible diary features lengthy musings about his situation. He was clearly torn between patriotism and love for his family, whom he knew he would never see again. His suicide mission was completed on April 12, 1945, five months before Japan’s surrender.