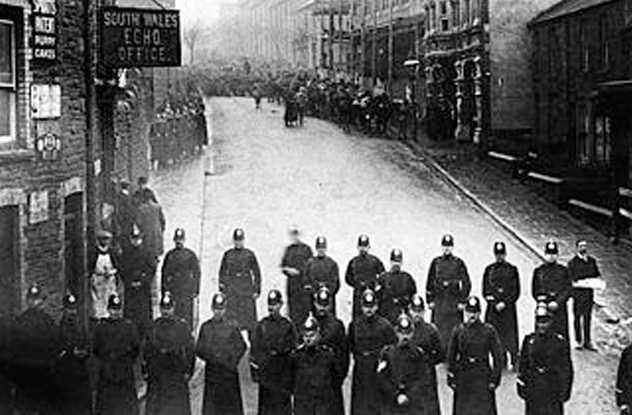

10Tonypandy Riots

Decades after his death, Winston Churchill is still a polarizing figure. He earned most people’s gratitude and respect for his leadership during World War II, but his political career was also littered with events that raised the ire of various groups. The Tonypandy Riots of 1910 happened long before Churchill took office as Prime Minister in 1940. He was Home Secretary back then and was tasked to intervene in a series of conflicts between police and coal miners in the Rhondda Valley in South Wales. The miners were protesting the mine owners who formed a coalition known as the Cambrian Combine to regulate prices and keep wages down. The miners went on strike and managed to shut down most of the local pits despite owners bringing in strikebreakers. On November 7, the miners had their first altercation with police officers and, later that night, engaged in a violent fight with Cardiff officers in Tonypandy Square. Churchill is usually remembered as the villain in this riot for sending in the military and allegedly allowing the use of ammunition. However, a new look at his correspondence shows that this wasn’t the full story. There is no evidence that a single shot was fired at Tonypandy, and Churchill was wary of sending in soldiers at all. A year after the Tonypandy Riots, coal miners went on strike throughout Britain. In turn, this led to the Coal Mines Act of 1912, securing a minimum wage for all coal miners.

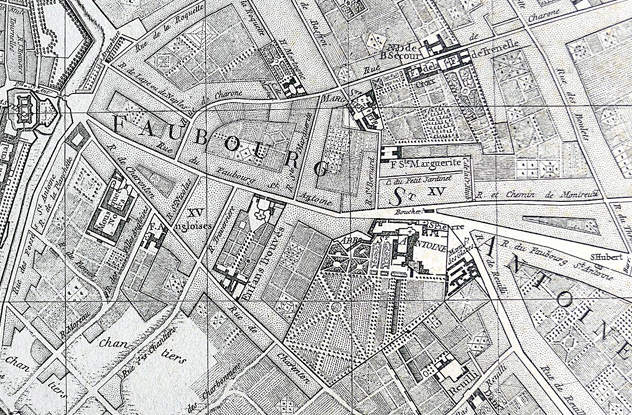

9Champagne Riots

Also in 1910, people in France were arguing over something different—grapes. Nowadays, champagne has a “controlled designation of origin.” True champagne can only be made using a specific method and grapes from certain areas in Champagne. Back in 1911, however, this measure had only been introduced for a few years and wasn’t yet clearly defined. The measure also favored the districts of Marne and Aisne while neglecting another winemaking region named Aube. Add to that a few years of bad crops and louse infestations, and grape growers had a lot to be angry about. Back then, most growers didn’t actually make their own champagne and simply sold their grapes to winemakers. Huge crop losses plus the increasing demand for champagne meant that winemakers had to buy their grapes someplace else but still wanted to call their product “champagne.” Like the British coal companies, Champagne houses colluded to keep grape prices low. Frustrations reached a boiling point in January 1911, when growers intercepted grape trucks and drove them into the river. They attacked several champagne-producing villages, with Ay getting the worst of it. The French government sent thousands of troops to deal with the riots. Afterward, it established a clearer Champagne zone that included Aube and developed a point system still used today to determine the value of specific grapes and prevent collusion. Marne growers lost their advantage, and new riots sparked in April. Eventually, an unusual event caused everyone involved to band together against a much bigger threat—World War I.

8Zoot Suit Riots

During the 1930s, the zoot suit was popular with minority youths, particularly Mexican Americans who formed their own subculture known as pachucos. And in 1943, the suit lent its name to one of the most violent riots in Los Angeles’s history. At that time, Los Angeles had one of the largest Latino populations in the country, which didn’t sit well with the predominantly white servicemen stationed throughout Southern California during World War II. In the minds of many, the zoot suit was closely associated with gang violence due to a high-profile case from 1942 dubbed the “Sleepy Lagoon murder” by the media. Furthermore, the zoot suit was also seen as unpatriotic due to its high fabric demands at a time when the War Production Board placed serious restrictions on the use of wool. In fact, most legit tailor companies didn’t even make zoot suits anymore, and prospective clients had to use bootleg tailors. Fights between US personnel and Latino youths started breaking out in 1943, getting more and more violent. The police stayed out of the conflict, the media encouraged it, and commanding officers ensured their men didn’t get arrested. The riot reached full scale on June 7. Around 5,000 soldiers and civilians went into black and Latino neighborhoods and attacked minorities on-site. Eventually, all military personnel had to be banned from Los Angeles, and wearing a zoot suit was made illegal. Due to outside pressures, a committee was established to find the source of the riots. They concluded, shockingly, that it was racism. This conflicted with Mayor Fletcher Bowron’s own findings, ascribing the riots to juvenile delinquents and white Southerners. The Zoot Suit Riots would become major influences on activists like Malcolm X and Cesar Chavez.

7Rice Riots

Terauchi Masatake served in the Japanese Imperial Army, where he reached the highest rank of gensui before becoming Japan’s prime minister in 1916. His reign ended just two years later, when the Terauchi cabinet was brought down by the worst riots in Japan’s modern history. As a military and political leader, Terauchi employed aggressive policies to increase Japan’s territory. Prior to World War I, he oversaw the annexation of Korea. He awarded loans to Chinese warlord Duan Qirui in exchange for claims to Chinese provinces. During World War I, Terauchi allied himself with the United Kingdom and dispatched ships in the Pacific and Indian Ocean to capture enemy colonies. Terauchi’s expansion had repercussions back home, where inflation made rice prices double in a short amount of time. The government was also stockpiling huge amounts of rice to send to overseas troops as Japan joined its allies in the Siberian Intervention of 1918. The first protest, a peaceful one, started in the small fishing village of Uozu in the Toyama Prefecture in July 1918. From here, protests lasting for days and involving thousands of people took place throughout the region. In August, protests spread to the nearby prefecture of Nagoya, where they escalated into violence, turning into full-blown riots. Almost one-third of Nagoya’s population of 430,000 took part in the riots, with over 10 million participants overall. Cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Kobe were ravaged by violent rioting as rice farmers were joined by other disgruntled laborers such as factory workers and miners.

6Reveillon Riots

One of the most important chapters in European history was the French Revolution between 1789 and 1799. It brought down the monarchy and instituted a republic in France under the leadership of Napoleon but also reduced the perceived value of monarchies globally, as more and more people wanted them replaced with democracies. The revolution didn’t happen overnight. It was centuries in the making and lasted for a decade before order was finally restored. That’s why it’s hard to pinpoint the exact beginning of the revolution, although most historians agree on the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789. Despite this, the Reveillon riots two months earlier are considered one of the first instances of violence during the revolution and a “dress rehearsal” for the real thing. The riots started due to comments made by Jean-Baptise Reveillon, a factory owner who said that he fondly remembered the days when a man could live on 15 sous a day. A seemingly innocent remark, it got a little misunderstood, and factory workers became worried that Reveillon was planning to lower wages. The riots started on April 26. At first, the protest was peaceful, but the French Guard interfered and opened fire on the crowds, killing dozens of protesters. Several participants were arrested and hanged in an effort to deter further outbursts. However, this display had the opposite effect, as crowds saw it as more oppression of the working class. This led to the most violent incident of all as the mob attacked and ransacked Reveillon’s home and factory.

5Esquilache Riots

A few decades before the French Revolution, Spain was attempting its own reform under the rule of Charles III. However, this one was about something completely different—the king wanted the people to change their style of dress. Instead of the traditional long cape and broad-brimmed hats, Charles wanted people to start wearing tricorn hats and short capes that were popular in France. These measures were spearheaded by one of Charles’s ministers, the Italian statesman Leopoldo de Gregorio, Marquis of Esquilache. At first, people simply ignored the new rules. They had more pressing concerns such as the increasing price of grain caused by a liberalization of the grain trade, also spearheaded by Esquilache. However, on March 10, 1766, the old garments were made illegal. It didn’t take long for the public to react. After a few small-scale protests, a full-blown riot erupted on March 23, when 6,000 people stormed Esquilache’s mansion. The next day, over 20,000 marched on the king’s palace in Madrid, forcing the king to give in to their demands. Fearing for his safety, the king fled Madrid and went to Aranjuez. Upon hearing this, the public grew concerned that he only accepted their demands to buy time, and new riots erupted. To fight this perception, Charles had to act on his promises, starting by dismissing Esquilache and restoring the old dress style. Once the riots were finished, Charles needed a scapegoat, and he seized the opportunity to persecute the Jesuits, leading to the Suppression of the Society of Jesus of 1767.

4Vata Pagan Riots

Instituting a new religion is a big task that doesn’t usually go smoothly. In fact, 1,000 years ago in Hungary, it caused a rebellion that overthrew the king. The king was Peter Urseolo, nephew to the first king of Hungary, Stephen I. Peter was in his second reign after being dethroned by his brother-in-law. However, with the help of the Holy Roman Empire, Urseolo managed to retake the throne in 1044. This short reign ended in 1046, during a very violent pagan rebellion that saw the slaughter of countless Christians. Bizarrely, the rebellion was led by a Christian, Andras, and his brothers, Bela and Levente. They were cousins of Peter Urseolo, and Andras considered himself the rightful king after being exiled for 15 years. They forged an alliance with a pagan chief named Vata, who commanded a large army that wanted to overthrow Christianity. Peter was dethroned and was allegedly killed by an angry mob, while Andras became king of Hungary. However, he never had any intention to stop Christian rule. If anything, he strengthened Christianity’s presence in Hungary. The Vata uprising became the last major attempt to abolish Christianity from the country. Also notable was a group of bishops murdered by the pagans, thus becoming martyrs and later saints. Among them was Gerard Sagredo, now known as Saint Gellert, one of the patron saints of Hungary. He was either stoned and lanced to death or placed in a cart and then thrown off a cliff into the Danube.

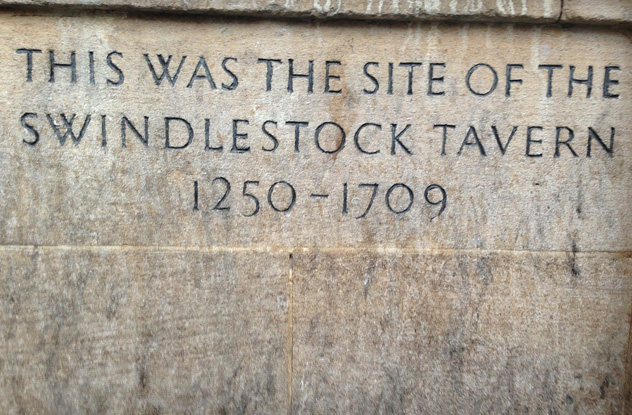

3St. Scholastica Day Riot

February 10, 1355, represents an infamous day in Oxford’s calendar—the St. Scholastica Day Riot. It was a day of violence and bloodshed that left over 90 people dead and established an Oxford tradition that would last for almost 500 years. Having one of the oldest universities in the world, Oxford is the poster child for a town-and-gown—a college city with two distinct communities representing the average people and the academics. While the relationship between the two groups is usually cordial nowadays, historically, it was more adversarial. In 14th-century Oxford, it was violent. The whole event started with a small group of students complaining about the wine at Oxford’s Swindlestock Tavern. Insults were traded, and, soon enough, both groups rallied hundreds of men to their side, and a fight erupted. The riot increased in size the following days as thousands more townsmen came to Oxford and marched on the university. Heavily outnumbered, the scholars trapped inside the college were either killed or beaten and thrown in prison while the angry mob ransacked most of Oxford University. After the riot, King Edward III helped the university and punished the town. The new Oxford charter gave the college several new privileges but also assigned it new responsibilities in an effort to keep the peace. As penance, the mayor of Oxford would have to walk bareheaded and pay one penny for each scholar killed each year on St. Scholastica Day. This penance lasted until 1825.

2Riots Of Toulouse

For France, the second half of the 16th century was dominated by the French Wars of Religion. Between 1562 and 1598, French Catholics and Protestants engaged in numerous civilian fights as well as military operations conducted by France’s aristocratic houses. One of the precursors of the civil war was the 1562 Riots of Toulouse, which saw religious tensions reach a boiling point and erupt in a violent outburst that lasted for over a week and left thousands dead. Although France was still a Catholic nation, the Reformed Church of France was constantly gaining new members (Huguenots), influenced by the teachings of Jean Calvin. The Catholic Church in Toulouse was concerned by the number of nearby towns that were now in the hands of Calvinists, as well as the large Huguenot population in Toulouse, which numbered anywhere from 4,000 to 20,000 members. Several events leading up to the riots added fuel to the fire. Word reached Toulouse of the Huguenot massacre at Vassy. Later, a riot erupted in Toulouse over the burial of a woman who had a Protestant husband but a Catholic family. Afterward, only Protestants were hanged, while all Catholic rioters were pardoned by the Parlement. This led to a failed Protestant insurrection. In retaliation, Parlement declared all Protestants traitors. Between May 13 and 17, 1562, new Catholic forces arrived in Toulouse and the Protestants were heavily outnumbered. Those who weren’t thrown in jail died in the streets. This led to massacres in other cities such as Sens and Tours that were only temporarily halted by the truce at Amboise in 1563.

1Bloody Sunday

Nowadays, Bloody Sunday refers to an incident in 1972 when British soldiers opened fire on unarmed civilians in Northern Ireland. But before this, Bloody Sunday chiefly referred to the riot of January 22, 1905, that acted as one of the triggers of the Russian Revolution. With the serf emancipation of 1861 came a new working class that was part of Russia’s industrialization. After abuse in the form of dangerous working conditions, long hours, and low wages, the new working class went on strike. On January 22, they staged a massive protest with anywhere from 3,000 to 50,000 participants, depending on the source. It was meant to be a peaceful demonstration—protesters would march on the Tsar’s Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg and deliver their petition. However, the army opened fire without provocation and killed between 100 (official sources) and 4,000 people (anti-government sources). Among the victims was the leader of the movement, father Georgy Gapon. As a direct result of Bloody Sunday, strikes were staged throughout the country, and this led to the Revolution of 1905. The revolution ended in 1906 with the implementation of new policies, including the adoption of a new constitution and multi-party system and the creation of new state assemblies called Dumas. However, these new measures were merely a temporary fix. Tsar Nicholas was directly blamed for Bloody Sunday. People had had enough of the tsarist autocracy and in 1917 launched another revolution that overthrew the tsar and led to the rise of the Soviet Union. Radu is into science and weird history. Share the knowledge on Twitter, or check out his website.