As we enter the 21st Century, political acts of self-immolation are, once again, on the rise. When Mohamed Bouazizi set himself alight, on Dec. 17, 2010, he sparked flames far greater than the ones that would ultimately kill him. The Tunisian man, an unemployed college graduate with children to feed, had tried to find work hawking vegetables, but was thwarted by police, who insulted him and confiscated his cart. His appeals of protest were ignored so, in a grisly act of protest and anguish, Bouazizi doused himself in gasoline and set himself ablaze. The act of self-immolation not only triggered the political crisis in Tunisia, which ousted the president on January 14, 2011, it has led to a series of protests and overthrown governments in the Middle East. It also inspired copycat self-immolations across North Africa. Because these acts almost always take place in public areas, many self-immolations have appeared on other lists, including Top Ten People Who Committed Suicide in Public, here at Listverse. This list includes no self-immolators from that previous Listverse list. Here are ten of the top acts of self-immolation.

The government or country in which a person lives is usually the target of protest for many self immolations. This self immolation of Per Axel Daniel Rank Arosenius was a bit more personal. After a dispute with the Swedish taxation authorities, on March 21 1981, Arosenius protested by setting himself on fire outside their office, in Nacka. He died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. He was 60 years old. Per Axel Daniel Rank Arosenius was a Swedish actor of mostly supporting parts. His most prominent film role was that of Soviet defector Boris Kusenov in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1969 film, Topaz.

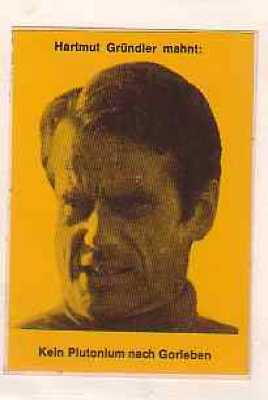

Hartmut Gründler was a German teacher from Tübingen, engaged in environmental protection. He opposed German energy policy and the construction of nuclear power plants. He protested against means to store radioactive nuclear waste. He handed out pamphlets in an attempt to educate the public about environmental matters that concerned him. He staged hunger strikes and all manner of non-violent protest trying to affect German policy. He even tried to open a dialogue with Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. On November 16, 1977, Gründler burned himself in Hamburg during the SPD Party Congress, out of protest against “the continued governmental misinformation” in the energy policy, particularly concerning the permanent disposal of nuclear waste. Two days before he self-immolated, he made a flyer with the heading “Please pass on… Self-immolation of a Life Protector – appeal against atomic lie…”, and, speaking of himself in the third person, he wrote, among other things, the following: “Gründler calls his action an act not of despair, but of resistance and resolution. To the inherent necessity of greed of profit, of confidence tricks, of taking people unawares here, and the inherent necessity of inertia and cowardice there, he wants to oppose the inherent necessity of conscience.”

Satī in Hindu is both a goddess figure, and an act that takes after her name. The goddess Sati, also known as Dakshayani, is a Hindu goddess of marital felicity and longevity; she is worshipped particularly by Hindu women who seek the long life of their husbands. Sati is said to have self-immolated because she was unable to bear her father, Daksha’s, humiliation of her husband, Shiva. The Goddess Sati took human birth and was born as a daughter of Daksha Prajāpati. As the daughter of Daksha, she is also known as Dākshāyani. The plan was that Sati would one day marry Shiva, the God of Gods. As she grew to womanhood, the idea of marrying anyone else (proposed by her father) became intolerable to Sati. After much courting on her part, Shiva finally acceded to her wishes and consented to make her his bride. An ecstatic Sati returned to her father’s home to await her bridegroom, but found her father less than elated by the turn of events. The wedding was, however, held in due course, though her father did not get on with his son-in-law. Daksha basically cut his daughter out of her family, to the point that he once organized a grand event to which all the Gods were invited, with the exception of Sati and Shiva. Wanting to be with her family, and though snubbed by this lack of an invitation, Sati went to the party anyway, but without Shiva. However, Sati was received coldly by her father. They were soon in the midst of a heated argument about the virtues (and alleged lack thereof) of Shiva. Every passing moment made it clearer to Sati that her father was incapable of appreciating her husband, Shiva. The realization then came to Sati that this abuse was being heaped on Shiva only because he had wed her; she was the cause of this dishonor to her husband. She was consumed by rage against her father and, calling up a prayer that she may, in some future birth, be born the daughter of a father whom she could respect, Sati invokes her yogic powers and immolated herself. Shiva sensed this catastrophe, and his rage was incomparable. He created Virabhadra and Bhadrakāli, two ferocious creatures who wreaked havoc and mayhem on the scene of the horrific incident. Nearly all those present were indiscriminately felled overnight. Daksha himself was decapitated. After the night of horror, Shiva, the all-forgiving, restored all those slain to life and granted them his blessings. Even the abusive and culpable Daksha was restored both his life and his kingship. His decapitated head was substituted for that of a goat. Having learned his lesson, Daksha spent his remaining years as a devotee of Shiva. The act of Sati grew into a religious funeral practice among some Hindu communities in which a recently widowed Hindu woman, either voluntarily or by use of force and coercion, would have immolated herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. The practice is rare and has been outlawed in India since 1829. The term may also be used to refer to the widow herself. The term sati is now sometimes interpreted as “chaste woman.”

Roop Kanwar was an 18-year old Rajput woman who committed sati on September 4, 1987, at Deorala village in Rajasthan, India. At the time of her death, she had been married for eight months to Maal Singh, who had died a day earlier at age 24, and had no children. There are conflicting reports regarding why she set herself on fire. Some claim Kanwar’s death was not voluntary. Many news reports say that she was forced to her death. However, other reports said that she told her brother-in-law to light the pyre when she was ready. Several thousand people attended the sati event. After her death, Roop Kanwar was hailed as a sati mata – a “sati” mother, or pure mother. The event quickly produced a public outcry in urban areas, pitting a modern Indian ideology and modernized society against an ancient and traditional act and set of beliefs. The incident also led to government action – first to state level laws to prevent such incidents, and then the adoption of the central government’s “The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act”. The original inquiries resulted in 45 people being charged with her murder but all of these were acquitted. A much-publicized later investigation led to the arrest of a large number of people from Deorala, said to have been present in the ceremony, or participants in it. Eventually, 11 people, including state politicians, were charged with glorification of sati. On January 31, 2004, a special court in Jaipur acquitted all of the 11 accused in the case, observing that the prosecution had failed to prove charges that they glorified sati.

The Soshigateli, or self-burners, were devout Russian Christians who regarded death by fire as “the only means of purification from the sins and pollution of the world.” Between 1855 and 1875 groups of soshigateli, numbering 15 to 100, burned themselves in large pits or dry buildings filled with brushwood. “About the year 1867, no less than seventeen hundred are reported to have voluntarily chosen death by fire near Tumen, in the Eastern Ural Mountains,” says Charles William Heckethorn, in his book, The secret societies of all ages and countries. These Christians were actually mimicking a form of self-immolation called “fire baptism” practiced by a 17th century Russian sect of Christianity known as the Old Believers. In 17th century Russia, Russian Orthodox dissenters of changes to the church being made by Patriarch Nikon refused to accept these liturgical reforms. Over a period of years, it is believed 20,000 of these “Old Believers” killed themselves through self-immolation.

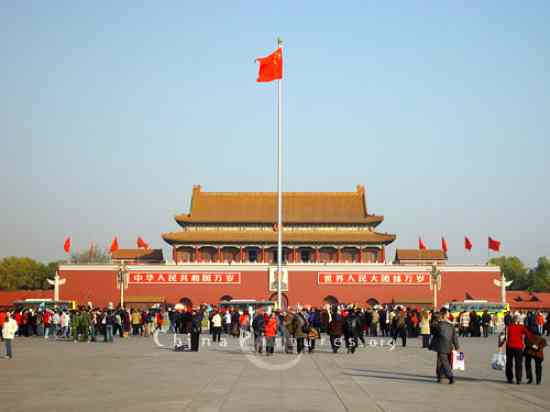

The Tiananmen Square self-immolation incident took place in Tiananmen Square in central Beijing, on the eve of Chinese New Year on January 23, 2001. There is no doubt that several people committed the act of self-immolation that day. What is disputed and still largely unknown is who these people were and why they did it. The official Chinese press claimed that five members of Falun Gong, a banned spiritual movement, set themselves on fire to protest the unfair treatment of Falun Gong by the Chinese government. The Falun Gong claimed the incident was a hoax staged by the Chinese government to turn public opinion against the group, and to justify the torture and imprisonment of its practitioners. The Falun Gong also stated that Falun Gong teachings explicitly forbid killing and violence, including suicide. According to Chinese state media, the five people were part of a group of seven who had traveled to the square together. These five people self-immolated and two of them would later die. One of them, Liu Chunling, died at Tiananmen under disputed circumstances and another, her 12-year-old daughter, Liu Siying, died in hospital several weeks later. The other three survived. A CNN crew present at the scene witnessed the five setting themselves ablaze and had just started filming when police intervened and detained the crew. The incident received international news coverage, and video footage was broadcast later in the People’s Republic of China by China Central Television (CCTV). The coverage in the CCTV showed images of Liu Siying burning, as well as interviews with the others in which they stated their belief that self-immolation would lead them to paradise, a belief that is not supported by Falun Gong’s teachings. The CCP’s claims about the incident remain unsubstantiated by outside parties, because no independent investigation has been allowed. Two weeks after the event, the Washington Post published an investigation into the identity of the two self-immolation victims who were killed, and found that “no one ever saw [them] practice Falun Gong.” The campaign of state propaganda that followed the event eroded public sympathy for Falun Gong, and the government began sanctioning “systematic use of violence” against the group.

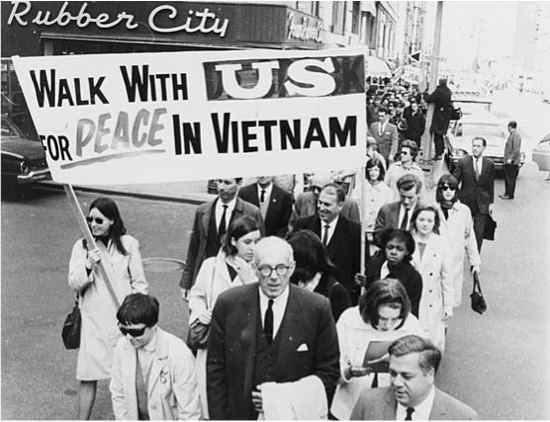

Though she is not as well known as the self-immolations of Norman Morrison and Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức in protest of the Vietnam war, Alice Herz does hold the distinction of being the first activist in the United States known to have immolated herself in protest of the escalating Vietnam War. Clearly she was following the example of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức who immolated himself in protest of the alleged oppression of Buddhists under the South Vietnamese government. A German of Jewish ancestry, Herz was a widow who left Germany for France with her daughter, Helga, in 1933, saying that she anticipated the advent of Nazism long before it arrived. They were living in France when Germany invaded, in 1940. After spending time in an internment camp, Alice and Helga eventually came to the United States, in 1942. They settled in Detroit, where Helga became a librarian at the Detroit Public Library and worked as a longtime peace activist. Herz self-immolated on March 16, 1965, in Detroit, Michigan, at the age of 82. A man and his two boys were driving by and saw her burning and put out the flames. She died of her injuries ten days later. Herz wrote a last testament, which she distributed to several friends and fellow activists before her death. The testament specifically refers to her decision to follow the protest methods of the Buddhist Vietnamese monks and nuns, whose acts of self-immolation had received worldwide attention. Confiding to a friend before her death, Herz remarked that she had used all of the accepted protest methods available to activists—including marching, protesting, and writing countless articles and letters—and she wondered what else she could do. After her death, Japanese author and philosopher Shingo Shibata established the Alice Herz Peace Fund. A plaza in Berlin (Alice Herz Platz) was named in her honor.

George Winne, Jr. may hold the distinction of being the last American to self-immolate in protest of the Vietnam war. Winne was born in Detroit, Michigan. His father was a captain in the U.S. Navy. Like Herz, he was inspired by the self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức Winne set himself on fire in a deliberate act of self-immolation in Revelle Plaza, on the campus of the University of California, San Diego on May 10, 1970, to protest the United States involvement in the war. The 23 year old student, a former member of an ROTC unit at the Colorado School of Mines, had no previous affiliation with any organized protests. Winne had recently completed his studies towards a degree in History in March, and had joined the History department as a graduate student. He would have attended graduation in June. Slightly after 4 p.m. on May 10, Winne ignited gasoline-soaked rags in his lap next to a sign that said “In God’s name, end this war.” He began to run and was knocked down by physics graduate student Keith Stowe, who tried to smother the flames. Winne died ten hours later at Scripps Hospital, after asking his mother to write a letter to President Nixon. His last words were “I believe in God and the hereafter and I will see you there.” Throughout the 1980s, student groups asked that a plaque be placed in memory of Winne. Although the Associated Students approved the proposal, it was blocked by the Revelle College Council. The UCSD Disorientation Manual 2001-2002 (p.43) says that the bricks upon which he lit himself on fire were removed from their original location in Revelle Plaza and currently rest next to a small memorial plaque, located in a grove of trees east of the campus library.

Showing the lasting appeal of self-immolation as a political statement, the most recent and newsworthy example is that of the death of Tarek al-Tayyib Muhammad ibn Bouazizi, known simply as Mohamed Bouazizi. Bouazizi was a Tunisian who had a hard life from the beginning, with his father dying when he was only 3. He was educated in a one-room country school in a small Tunisian village and he never graduated from high school, Bouazizi had worked various jobs since he was ten, and in his late teens he quit school in order to work full-time. Bouazizi lived in a modest stucco home, a twenty-minute walk from the center of Sidi Bouzid, a rural town in Tunisia burdened by corruption and suffering an unemployment rate estimated at 30%., He applied to join the army, but was refused, and several subsequent job applications went nowhere. He supported his mother, uncle and younger siblings, including paying for one of his sisters to attend university, by earning approximately $140 per month selling his produce on the street in Sidi Bouzid. Local police officers had harassed Bouazizi for years, regularly confiscating his small wheelbarrow of produce; but Bouazizi had few options to try to make a living, so he continued to work as a street vendor. On the morning of December 17, 2010, soon after setting up his cart, the police confiscated his wares again, ostensibly because Bouazizi did not have a vendor’s permit, although no permit is needed to sell from a cart. It was also claimed that Bouazizi did not have the funds to bribe the police officials to allow his street vending to continue. Bouazizi was publicly humiliated when a 45-year-old female municipal official, slapped him in the face, spat at him, confiscated his electronic weighing scales, and tossed aside his fruit and vegetable cart; all while her two colleagues assisted her in beating him. It was also stated that she made a slur against his deceased father. Her gender made his humiliation worse due to expectations in the Arab world. Angered by the confrontation, Bouazizi went to the governor’s office to complain. Following the governor’s refusal to see or listen to him, even after Bouazizi was quoted as saying “‘If you don’t see me, I’ll burn myself’,” he acquired a can of gasoline. He doused himself in front of a local government building and set himself alight. This act became the catalyst for the 2010–2011 Tunisian uprising, sparking deadly demonstrations and riots throughout Tunisia in protest of social and political issues in the country. Anger and violence intensified following Bouazizi’s death, leading then-President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to step down after 23 years in power. Following Bouazizi’s self-immolation, several other men have emulated this act in other Arab republics, in an attempt to bring an end to the oppression they face from corrupt, autocratic governments. Although none have elicited significant results, they and Bouazizi are being hailed by some as “heroic martyrs of a new Middle Eastern revolution.” Inspired by Bouazizi’s act, and the success of the people overthrowing the oppressive leaders in Tunisia, oppressed people in many Middle Eastern countries have followed suit. The subsequent fall of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, and the looming overthrow of Muammar Qhadafi in Libya can be directly traced to this single act of self immolation.

Inspired by the self immolation of Bouazizi, which led to the successful overthrow of the hated Ben Ali regime in Tunisia, several other acts of self immolation have occurred around the Middle East. Much like those who were inspired to protest the Vietnam war after the self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức, others have been inspired to protest repressive regimes in countries throughout the Middle East, and also in Europe. In Algeria, during protests against rising food prices and spreading unemployment, there have been several cases of self immolation. The first reported case following Bouazizi’s death was Mohsen Bouterfif, a 37-year-old father of two, who set himself on fire when the mayor of Boukhadra refused to meet with him and others regarding employment and housing requests. According to a report in El-Watan, the mayor challenged him, saying if he had courage he would immolate himself by fire as Bouazizi had done. On January 13, 2011, Bouterfif did just that. He died on January 24, 2011. Maamir Lotfi, a 36-year-old unemployed father of six who was denied a meeting with the governor, burned himself in front of the El Oued town hall on January 17, 2011. He died on February 12. Abdelhafid Boudechicha, a 29-year-old day laborer who lived with his parents and five siblings, burned himself in Medjana on January 28, 2011, over employment and housing issues. He died the following day. In Egypt, Abdou Abdel-Moneim Jaafar, a 49-year-old restaurant owner, set himself alight in front of the Egyptian Parliament. His act of protest contributed to the instigation of weeks of protest and, later, the resignation of Egyptian then-President Hosni Mubarak, on February 11, 2011. In Saudi Arabia, an unidentified 65-year-old man died on January 21, 2011, after setting himself on fire in the town of Samtah, Jizan. This was apparently the first known case of self-immolation in Saudi Arabia. Not all of these cases of self immolation, with the exception of Egypt, provoked the same kind of popular reaction that Bouazizi’s case did in Tunisia. However, the mass popular uprising throughout the Middle East that has come about, subsequent to Bouazizi’s self immolation, has forced countries such as Algeria, Yemen and Jordan to make major concessions in response to significant protests. As such, these men and Bouazizi are being hailed by some as “heroic martyrs of a new Arab revolution.” The wave of copycat incidents reached Europe on February 11, 2011, in a case very similar to Bouazizi’s. Noureddine Adnane, a 27-year-old Moroccan street vendor, set himself on fire in Palermo, Sicily, in protest of the confiscation of his wares and the harassment that was allegedly inflicted on him by municipal officials. He died five days later.

Alfredo Ormando was a gay Italian writer who set himself on fire in Saint Peter’s Square, in Rome, to protest the attitudes and policies of the Roman Catholic Church regarding homosexual Christians. On January 13, 1998, Alfredo Ormando, a 39-year old Italian writer, arrived in Rome just as the sun was rising. After his long journey from Sicily, he found his way to the empty piazza of the Vatican and, facing the entrance to the Basilica, knelt down as if to pray. He made a rapid hand gesture and suddenly was engulfed in flames. Before the Church and, he hoped, the world, Alfredo Ormando had set himself on fire. He left the following statement before his death: “I hope they’ll understand the message I want to leave: it is a form of protest against the Church that demonizes homosexuality and at the same time all of nature, because homosexuality is a child of Mother Nature.” Two policemen put out the flames and he was brought to Sant’Eugenio hospital in critical condition. He died there 11 days later.