It’s easy to think that these aren’t normal, that this is something new. But massacres have occurred in almost every developed country, often committed by the governments themselves. Here are 10 of the most tragic examples.

10 The Athens Polytechnic UprisingGreece

In 1973, Greece was still controlled by a military dictatorship. By the end of the year, a democracy bloomed, but it was not a bloodless transition. On November 14, students began to gather at Athens Polytechnic University. They occupied the buildings on campus and began chanting anti-American and pro-democracy slogans. Large numbers of police encircled the campus. Over the next two days, the uprising spread. More students joined in, and the campus radio station began to broadcast pleas for the overthrow of the government. These were taken up by other radio stations across the country. That was when the regime began to crack down, leading to violent clashes between police and students. At midnight, tanks rolled into the street and rammed down the main gates of the university. Soldiers and police officers began to shoot into crowds. By the next morning, 39 students were dead. Their sacrifice is seen as the turning point in the fight against the Greek dictatorship.

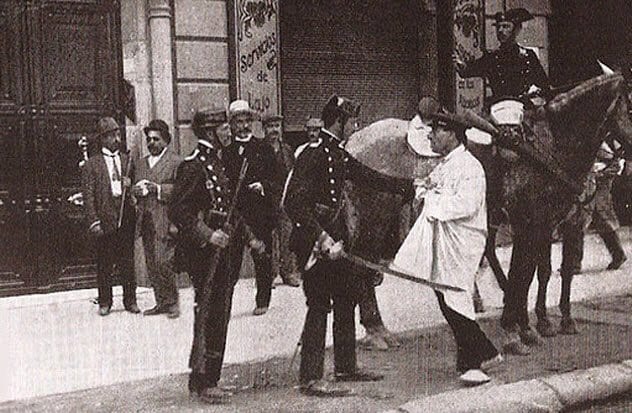

9 The Tragic WeekSpain

Depending on whom you ask, the Tragic Week between July 25 and August 2, 1909, was either, well, a tragic week or a glorious revolution. From the perspective of the rich, it was terrible. Poor laborers in Barcelona and other towns in Catalonia (a region of Spain) revolted, led by a coalition of union leaders and anarchists. They burned hundreds of buildings, mostly belonging to the church. And all they were complaining about was a tiny draft to fight a little colonial war in Morocco—which couldn’t be that bad, right? The poor disagreed. They rioted after the Spanish ordered a draft, which men could get out of by paying a fine of 6,000 reales. (The average day wage of a laborer was between 5 and 20). The draft included men who had already served in previous wars, even though they’d been promised they would never be drafted again. For that reason and a whole lot of hatred toward elites and the church, the poor flocked to massive demonstrations, which soon turned distinctly rioty. Eventually, the army was brought in and began to fire on the crowds. By the end of the Tragic Week, over 100 protesters were dead. After the protests, the Spanish government cracked down harshly, arresting thousands of people.

8 The Vyborg MassacreFinland

For a long time, Finland was part of Russia. When Finland seceded, two competing forces, the Whites and the Reds, were interested in governing the new country. The Whites were anti-Communist, the Reds pro-Communist. The resulting civil war was won by the Whites, which is why Finns today are capitalists. During this civil war, the Vyborg massacre took place in 1918. Back then, Finland owned a large part of what is modern-day Russia. So there were a lot of Russians living in Finland, including in Vyborg. Since this was soon after the Russian Revolution, there was a bit of an association between Russians and Communism. When the Finnish White Army took the town after a difficult battle and learned that some members of the Red Army were still hiding there, it didn’t take the Whites long to decide on a group of suspects. This happened even though the Russian population of the town was mostly pro-White. To deal with their made-up problem, the White Army rounded up all the Russian men in the city who could potentially be hidden Red Army members and executed them. Hundreds of people between the ages of 12 and 60 were massacred.

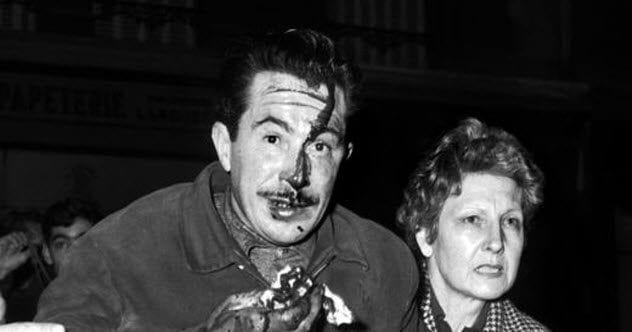

7 The Charonne Metro Station MassacreFrance

Once upon a time, it was practically illegal to protest in France. The price, however, was typically not death. As one witness to the Charonne Metro Station massacre recalled, “We knew the demonstration had been declared illegal, but we went with the idea we’d just be beaten up as usual rather than killed.” On February 8, 1962, the French police killed nine demonstrators inside the Charonne Metro Station in Paris. The demonstrators were mostly labor leaders, joining in a protest against the French colonial war in Algeria. What makes the Charonne massacre so extraordinary is how ruthless it was. The French police waited until people were crowded into the station before dropping heavy weights from above, crushing people’s skulls instantly. It wasn’t an attempt at crowd control; it was just murder.

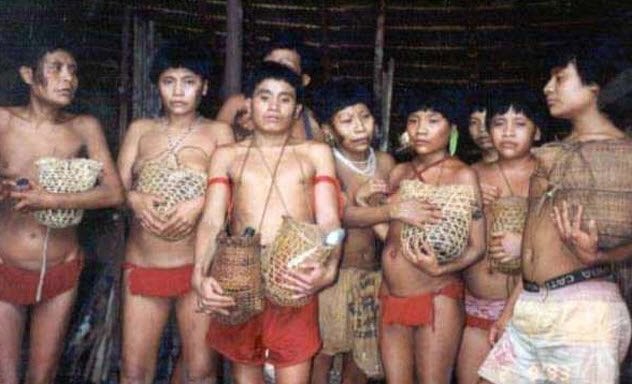

6 Haximu MassacreBrazil

But in these essentially lawless parts of the country, there are two things: indigenous people and enough natural resources to make someone very, very rich. When the locations of those two things just happen to coincide, the results can be genocidal. The Haximu massacre is a good example of that. In 1993, gold prospectors went into the jungle and encountered the Yanomami people. Conflict began quickly. The prospectors wanted the Yanomami’s land, and the Yanomami wanted the prospectors to leave. The conflict escalated when the prospectors attacked a Yanomami village, eventually killing 16 people. The prospectors were never charged with anything. In fact, their later activities caused an outbreak of malaria, killing even more Yanomami.

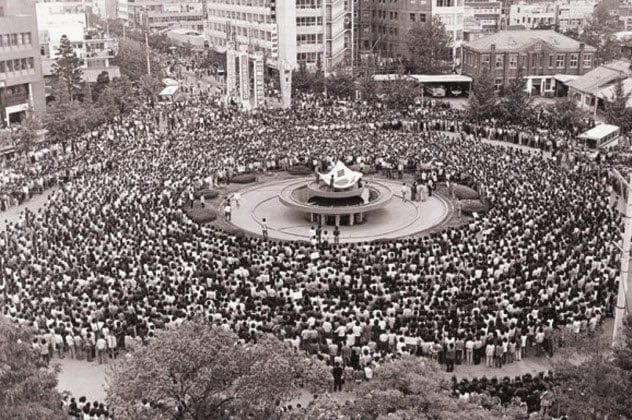

5 Gwangju UprisingSouth Korea

South Korea used to be a military dictatorship. It took years for the country to liberate itself, but one of the pivotal moments is easy to identify: the Gwangju Uprising. Gwangju is a city in the southern area of South Korea, and on May 18, 1980, the entire population rose up in revolt. Nearly a quarter million people took to the streets and forced 18,000 government troops to retreat from the city. The people declared a democracy and urged the rest of South Korea to join them. The revolt failed. Over the next week, the military surrounded the city. On May 27, they invaded. Tanks rolled through the streets, and helicopters fired indiscriminately. According to government statistics, over 200 civilians were killed, but some put the figure at closer to 2,000. Although the Gwangju Uprising was suppressed, it served as an important rallying point and symbol on South Korea’s path toward democracy.

4 The General StrikeArgentina

In the first part of the 20th century, Argentina was among the wealthiest countries on Earth and looked ready to become a power in its own right. It was in that context that the General Strike of 1919 occurred. On January 7, 1919, workers in Buenos Aires began to strike, calling for crazy demands like an eight-hour workday. The situation soon became violent, pitting the middle and upper classes against the working class. The deaths began on January 9 when police and firefighters ambushed a group of workers returning from a funeral, killing 50 of them. That was the starting bell. Soon, the military attacked lower-class neighborhoods, and by the end of the day, 100 people were dead. The next day, 50 more were killed and the army surrounded Buenos Aires. On January 11, the violence became dominated by anti-Semitic vigilantes. They attacked Jewish neighborhoods, killing people and burning synagogues. By the time the strikes ended on the January 13, no one was sure exactly how many were dead. But all sources put the number in the hundreds, if not the thousands. Almost all were workers.

3 Kafr Qasim MassacreIsrael

The Kafr Qasim massacre occurred on October 29, 1956, near the village of Kafr Qasim. It was located on what was then the Green Line separating Israel from the Jordanian West Bank. Due to a war in the Sinai Peninsula happening simultaneously, Israeli soldiers all along the border were put on alert and told that a curfew was in effect. Anyone who broke it could be shot. No one, however, thought to tell the residents of Kafr Qasim that. As they returned unaware from the fields near the village, three Israeli soldiers opened fire on them. By the time the firing stopped, 49 people were dead. The soldiers were all charged but eventually pardoned. Their commander was forced to pay a symbolic 10-cent fine. In December 2007, Shimon Peres, the president of Israel, formally apologized for the massacre.

2 Colfax MassacreUnited States

As some have pointed out, the Civil War did not end racism. Although it was pretty obvious from the moment the war ended, it took the Colfax massacre to make it absolutely clear. In 1872, voters in Louisiana elected two separate governors simultaneously—one Republican, one Democrat. At the time, African-Americans had just been given the right to vote. They were coming out for Republicans, the representatives of the party of Lincoln. The federal government took the side of the Republicans and sent in troops. In response, Southern Democrats founded their own government with their own army, the White League. Their goal was to suppress African-Americans and Republicans and ensure that only white Democrats could take power in Louisiana. Violence grew between the White League and the overwhelmingly black Louisiana State Militia. It came to a head in the small town of Colfax, where members of the White League managed to defeat a force of state militia and offered to let them surrender. The militia took them up on their offer, and the White League promptly massacred around 100 unarmed African-American militia members. After the Colfax massacre, the situation in Louisiana escalated to a war between the White League and the federal government.

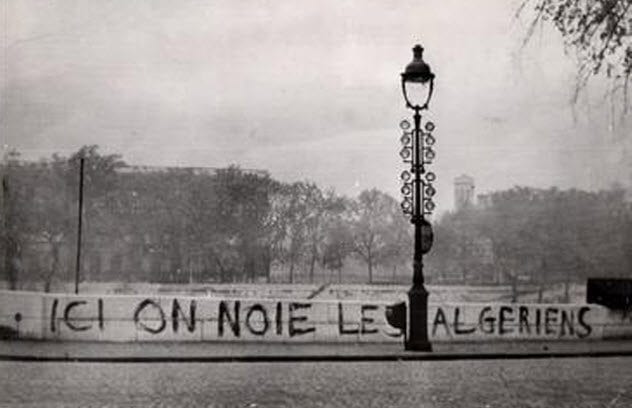

1 Paris MassacreFrance

Fifty years before ISIS decided to target Paris, the city suffered another, even larger massacre. This time, it was at the hands of the Paris police. The details of it were hidden from the French public for years. Even today, the exact death count is unknown. In 1961, France was fighting for control of its colony Algeria. There was strong opposition to the war in France, and on October 17, 1961, a large peaceful protest gathered in the center of Paris. The commander of the Paris police at the time was Maurice Papon. Years later, he would be tried and convicted for crimes against humanity committed during World War II. It was during the course of his trial that information about the Paris massacre of 1961 was uncovered. Led by Papon, the police surrounded and attacked the protesters. The police beat the protesters to death with clubs and shot them before dumping their bodies off bridges into the Seine. By the end of the day, 200 people were dead in the heart of Paris. The next day, the police told the newspapers that only three people had died. The story told by the police dominated the media for years. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the truth was revealed. The French government didn’t apologize for or recognize the massacre until 2012. Jonathan Vincent is new at this, so he doesn’t have a blog or many cool things to share.