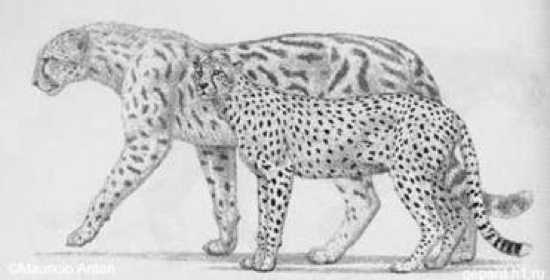

10 Giant Cheetah

The Giant Cheetah (Acinonyx pardinensis) belonged to the same genus as our modern-day Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and probably looked very similar, but it was much bigger. At around 120-150 kgs (265-331 lbs), it was as large as an African lioness and was able to take on larger prey than its delicate modern-day counterpart. The Giant Cheetah was also adapted to fast running, but there’s some debate on whether it could run as fast as the modern Cheetah due to its heavier weight, which, according to some, probably made it somewhat slower. Others, however, have suggested that the Giant Cheetah, having longer legs and a bigger heart and lungs, could probably run as fast, or even faster, than the cheetah does today—that’s over 115 kph (72 mph)! The Giant Cheetah lived in Europe and Asia (from Germany and France to India and China) during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs; it went extinct during the last Ice Age. Due to its living in colder environments than today’s Cheetahs, it is possible that the Giant Cheetah had longer fur and perhaps lighter coloration.

9 Xenosmilus

Xenosmilus is a relative to Smilodon (the ever famous “sabertoothed tiger”), but instead of having long, blade-like fangs, it had shorter and thicker teeth. All of its teeth (not only the canines) had serrated edges to cut through flesh and were more like the teeth of a shark or a carnivorous dinosaur than the teeth of modern-day cats. Xenosmilus didn’t strangle its prey as cats do today; it only had to bite off a huge chunk of flesh from its victim and wait until it bled to death. A Xenosmilus’s kill was much bloodier and messier than that of any big cat you might see at the zoo! Xenosmilus was a very big cat by today’s standards—at 180-230 kgs (397-507 lbs). It was as big as most adult male lions and tigers and was much more robust, with shorter, stronger limbs and a very powerful neck. The remains of this cat have been found in Florida, along with those of giant prehistoric peccaries (pig-like animals), which were seemingly its favorite meal. It lived during the Pleistocene period, but no one knows exactly when it went extinct; whether it encountered (or ate) humans or not is anyone’s guess.

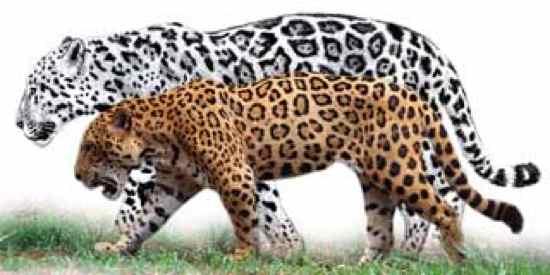

8 Giant Jaguar

Jaguars today are rather smallish cats if compared to lions or tigers; they usually average 60-100 kgs (132-220 lbs), and the largest males (recorded from South America) were around 150 kgs (330 lbs), about the size of an African lioness. In prehistoric times, however, both North and South America were home to gigantic jaguars, belonging to the same species as modern-day jags (Panthera onca) but much bigger. These giant jaguars also had longer limbs and tails than jaguars living today; scientists believe that jaguars used to be open plain denizens, but that competition with American lions and other big cats forced them to adapt to more forested environments, where they developed their modern short-legged appearance. Giant prehistoric jaguars were about the size of a fully grown lion or tiger and were probably several times stronger, with a much stronger bite. There are two subspecies of prehistoric giant jaguars known to date; Panthera onca augusta, from North America, and Panthera onca messembrina, from South America (also known as the Patagonian panther). Both of them were active during the Pleistocene period but went extinct about 11.000 years ago, during the last Ice Age.

7 European Jaguar

Unlike the Giant Jaguar mentioned before, the European Jaguar or Panthera gombaszoegensis did not belong to the same species as modern-day jags. Nobody knows what the European Jaguar looked like; some scientists have suggested that it probably looked much like a modern-day jaguar (hence the name), or perhaps, a cross between a lion and a jaguar. A fossil feline from Eastern Africa has been said to resemble the European Jaguar and is described as having “tiger-like” features as well. Regardless of its external appearance, it is obvious that it was a huge predator, weighing up to 210 kgs (463 lbs) or more, and probably at the top of the food chain in Europe, 1.5 million years ago. Its fossil remains have been found in Germany, France, England, Spain, and the Netherlands.

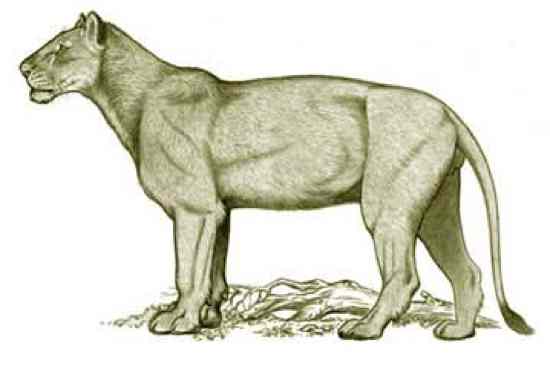

6 Cave Lion

The Cave Lion was a gigantic subspecies of lion, weighing up to 300 kgs (661 lbs) or more (and therefore, being as large as the Amur or Siberian tiger, the largest modern-day cat). It was one of the most dangerous and powerful predators during the last Ice Age in Europe, and there is evidence that it was feared, and perhaps worshiped, by prehistoric humans. Plenty of cave paintings and a few statuettes have been found depicting the Cave Lion. Interestingly, these show the animal as having no mane, barely a ruff around the neck sometimes, as in modern-day tigers. Confusingly, some cave paintings also show the Cave Lion as having faint stripes on its legs and tail. This has led some scientists to suggest that perhaps the Cave Lion was actually more related to the Tiger. However, genetic studies on the ancient bones have confirmed the original idea that the Cave Lion is, indeed, a lion after all—albeit, if cave artists are to be trusted, a very unusual looking one.

5 Homotherium

Also known as the “Scimitar cat,” Homotherium was one of the most successful felines in prehistoric times, being found in North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. It adapted well to various habitats, including the sub-Arctic tundra, and survived for five million years until its extinction 10,000 years ago. Homotherium was seemingly a pack hunter, adapted to fast running and active mostly during the day (thus avoiding competition with other, nocturnal predators). It had very long forelegs and shorter hind legs, which gave it a slightly hyena-like appearance. Although Homotherium is not very famous for its size, some fossil remains of a Scimitar cat unearthed recently in the North Sea suggest that they could reach 400 kgs (882 lbs) in weight, being larger than modern-day Siberian tigers. If you are wondering what these enormous, pack-hunting cats ate, some paleontologists believe that they were quite skilled mammoth hunters. However, their ability to run at high speed would allow them to chase after fleet-footed animals as well.

4 Machairodus kabir

Despite Smilodon’s fame as the classic “sabertooth tiger,” its short tail and different body proportions were very different from an actual tiger. Machairodus, on the other hand, probably looked pretty much like a giant tiger with saber teeth; it had very tiger-like proportions and a long tail, although it is impossible to know if it had stripes, spots, or any other kind of fur markings. Machairodus is seldom mentioned as a giant feline, but some fossil remains found in Chad, Africa, (and classified as a new species, Machairodus kabir) suggest that this creature was among the largest cats of all times—weighing up to 490 kgs (1080 lbs) or perhaps 500 kgs (1102 lbs), being “the size of a horse.” It fed on elephants, rhinos, and other large herbivores, which were abundant at the time. Machairodus kabir probably looked somewhat like the gigantic “sabertooth tiger” in the film 10.000 B.C, although sadly, it went extinct during the Miocene period, long before the appearance of humans.

3 American Lion

Often called the largest cat of all times, the American lion or Panthera atrox is probably the best known of all prehistoric cats after Smilodon. It lived in both North and South America (from Alaska to Peru) during the Pleistocene epoch and went extinct 11,000 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age. Most scientists believe that the American Lion was a gigantic relative to modern lions, perhaps even belonging to the same species (in which case the correct name would be Panthera leo atrox). However, others are not so sure and suggest that the American Lion, although closely related to the lion, was a separate species and probably looked quite different on the outside. Recently, it was suggested that the American Lion was probably more similar to the jaguar. One thing is certain; the American Lion was the largest cat in North America during the Ice Age, weighing up to 470 kgs (1036 lbs), perhaps even 500 kgs (1102 lbs), and being able to take on very large prey. There is still some debate about its hunting technique, for although modern-day lions hunt in groups, American Lion remains are scarce, suggesting that these cats were probably solitary hunters. This will make sense if we consider that the North American Smilodon fatalis, a species of sabertooth, was seemingly a pack hunter. By hunting alone and preying on different animals, it may be that the American Lion avoided competition with the sabertooth, explaining why both cats coexisted successfully for such a long time.

2 Smilodon

The ever-popular “sabertooth tiger,” Smilodon, is one of the most famous prehistoric predators and also one of the most formidable. At least three species were living in both North and South America; the smallest species, Smilodon gracilis, was about the size of a modern-day jaguar, while Smilodon fatalis was as big as a lion. However, the South American species Smilodon populator dwarfed both of them, weighing 300 kgs (661 lbs) on average and reaching up to 500 kgs (1102 lbs) when fully grown! Smilodon was not as agile as modern-day big cats, but it was immensely powerful, with thicker, stronger limbs and neck than modern-day cats, and particularly long claws to hold on to prey. Its fangs could reach 30 cms (12″) in length and were perfect for causing mortal injury to mammoths, ground sloths, and possibly any large animal unlucky enough to be ambushed by this super predator. Smilodon went extinct 10,000 years ago, meaning it encountered humans and probably hunted them once in a while. But perhaps the most amazing thing about Smilodon is that it is the only prehistoric cat known to have caused the extinction of an entire species. The victim was another formidable predator, the saber-toothed marsupial or marsupial relative known as Thylacosmilus. This beast ruled South America for millions of years until the sea levels became lower and North America became connected to South America. Smilodon, native to North America, made the journey to South America about 2 million years ago. Thylacosmilus disappeared practically at the same time, outcompeted, and perhaps even hunted to extinction by the cat. In other words, Smilodon basically conquered an entire continent, driving its less adaptable competitors to extinction.

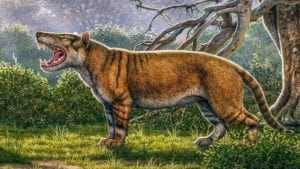

1 Simbakubwa kutokaafrika

While the Smilodon and others on this list may be more well-known, a new species finally identified in 2019 now reigns as the largest of the prehistoric cats (apologies to the Smilodon!). Originally, based on the size of the jaw and teeth, the fossil remains were believed to have been a species of great ape. Significantly larger than a tiger, lion, or polar bear with a skull comparable with a rhinoceros, this ancient predator cat, known as Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, wasn’t discovered in the field—but in a long-neglected museum drawer. Two paleontologists from Ohio University found the new species of the large mammal at the National Museums of Kenya. According to a press release from Ohio University, they had been previously excavated within the country and were “not given a great deal of attention.” The large cats lived in Africa and were likely solitary hunters. Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, which means “big lion from Africa” in Swahili, belongs to a long-extinct group of some of the largest meat-eating land mammals known as Hyainailourine hyaenodonts, which roamed Earth about 22 million years ago. Despite the name, this animal is not a lion or related to the cats; instead, it is a member of a group of mammals who had teeth closely resembling a hyena, even though they are also unrelated. Based on its massive teeth, scientists estimate that the big cat weighed about 1,308 kgs (1,888 lbs)! For comparison, modern adult lions and tigers weigh about 180 kg (400 lbs). The cat also had an equally impressive jaw and blade-like teeth. In addition to the front canines, Simbakubwa had three pairs of meat-slicing teeth in the back—to put that into perspective—carnivores like the modern lions, domestic cats, raccoons, and wolves only have one pair.