10Glen Larson

The late ’70s were a good time for American science fiction. As Star Wars debuted and Star Trek found new life on the big screen, Hollywood executives were scrambling for a piece of the space-pie. It was against this backdrop that a California-born Mormon named Glen Larson secured funding for his own sci-fi epic: Battlestar Galactica. After scoring a couple of hits with his band The Four Preps, Larson transitioned into the TV industry in the late ’60s. His early producing credits included hits like Alias Smith And Jones and The Six Million Dollar Man. While working on those, Larson spent 10 years developing and pitching his pet project, a sci-fi epic dubbed Adam’s Ark, which was originally conceived as a series of TV movies. After being renamed and reworked as a TV series, Battlestar Galactica debuted on ABC in 1978. Larson drew strongly on his Mormon background to create the spiritual and mystical elements of the show. Characters spoke of being married for “time and all eternity,” echoing Mormon teachings, while the planet Kobol sounds suspiciously like Kolob, a star mentioned briefly in Mormon scripture. The original human colonies were led by the Quorum of Twelve, which is also name of a senior body in the LDS church. In the episode “War Of The Gods,” a mysterious angelic being states “As you are now, we once were; as we are now, you may become,” which is a paraphrase of LDS President Lorenzo Snow’s declaration that “As man is, God once was; as God is, man may become.” Galactica was always a high-risk undertaking: Each episode cost $1 million, which was considered obscene at the time. To make matters worse, the series suffered from low ratings and Fox sued over perceived similarities to Star Wars. It was canceled after one season, but quickly became a beloved cult classic and eventually scored an acclaimed reboot. Larson went on to create TV megahits like Magnum P.I. and Knight Rider, before passing away in 2014.

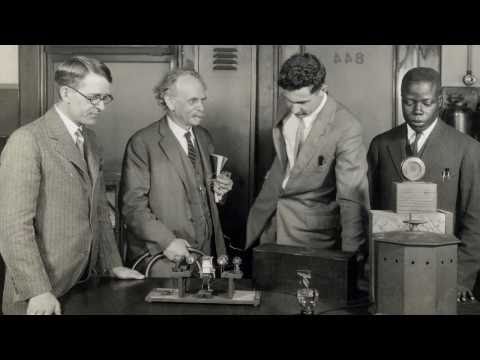

9Lester Wire

No sooner had automobiles became a viable mode of travel than city streets were clogged by irresponsible motorists flouting traffic laws and getting into accidents. In the Mormon hub of Salt Lake City, police officer Lester Wire was given the task of creating the city’s first traffic patrol squad in 1912. At first, Wire and his men would stand on raised platforms in the middle of intersections and attempt to direct traffic via hand signals and shouting. Since that’s insane, Wire decided to figure out a better way. The earliest traffic lights were actually a set of gaslights installed outside the British Parliament in 1868. The British gave up on the idea when they exploded in 1869. Wire used electricity for his design and fitted his “flashing bird house” with red and green lights, which were originally controlled from a safe distance by a traffic cop. Initially, most local drivers refused to pay much attention to the contraption, and crowds would gather just to see it light up. Fortunately, enough citizens were enthused by the design that they petitioned the authorities to install more lights around the city. The success of the Salt Lake City system impressed police forces from other cities and traffic lights were soon given the green light all around the country. Other inventors improved on Wire’s design. Another police officer named William Potts added a yellow light in 1920, creating the standard red-yellow-green color scheme (Potts’ creation is pictured above). A few years later, the lights were automated and the modern traffic light finally took shape. It’s now hard to imagine a world without the invention of a young Salt Lake City policeman.

8Tracy Hall

The story of H. Tracy Hall is one of the most disheartening in scientific history. In a stroke of brilliance, Hall invented synthetic diamonds and changed the modern world. In return, he received $10 and had his apparatus confiscated by the United States government. Hall began working for General Electric in 1953, when GE was investing huge sums in expensive, high-pressure machines. Believing he could create diamonds by pressurizing carbon, Hall built his own pressure machine, but the design leaked so much water from its hydraulics that rubber boots had to be worn around it. When Hall requested $1,000 to make a new machine, GE refused. Not to be discouraged, Hall convinced a friend to put in overtime in the machine shop, and together they built an improved press. In December 1954, Hall ran a test of his press. After opening the machine “my hands began to tremble; my heart beat rapidly; my knees weakened and no longer gave support.” He had created diamonds. When Hall informed GE of the experiment, the company publicized the breakthrough without crediting his improved press. By way of a reward, Hall received an offensively small $10 savings bond. Disgusted by his treatment, Hall left GE and began to teach at Brigham Young University. He planned to continue his research there, only to discover that the government had classified his machine, preventing him from doing further work on it. So he invented another press instead. The government classified that, too. Fortunately, the authorities eventually relented and Hall formed his own company to create artificial diamonds. Today, Hall’s process has not only created less expensive jewelry, but allowed synthetic diamonds to be widely used in manufacturing, research, and industry.

7Leigh Harline

While Mormon musicians are not uncommon, none have had the influence of Leigh Harline. Born in the 1920s to Swedish immigrant parents, Harline was baptized into the church when he turned eight and later studied music at the University of Utah under J. Spencer Cornwall, leader of the famed Mormon Tabernacle Choir. After graduating, Harline moved to California and worked as a composer and announcer for various radio stations in Los Angeles and San Francisco. In 1931, he wrote and performed the music for the first transcontinental radio broadcast originating from the West Coast. The broadcast brought Harline into the national spotlight. More importantly, it captured the attention of a filmmaker named Walt Disney. Originally, Disney brought Harline in to help score the Silly Symphonies cartoons. However, he soon moved to Disney’s most ambitious project yet: a feature-length animated film entitled Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs. Four of the top Disney composers worked on the film, with Harline writing most of the incidental music. As you probably know, the movie was a huge success and Disney quickly began working on Pinocchio, which would feature unprecedented advances in animation design. To score the new movie, Disney turned to Leigh Harline and lyricist Ned Washington. Together, Harline and Washington created some of the most iconic music in movie history. Harline’s score used the classical technique of leitmotif, or associating characters and events with certain musical cues. Although the technique was used in earlier films, it did not reach a large audience until Pinocchio. Most modern movie soundtracks now use this technique. The most iconic part of the Pinocchio score was Harline’s song “When You Wish Upon A Star.” Though simple in musical construction and lyrics, the song was an instant hit, netting Harline an Academy Award in 1940. It’s now arguably the most iconic song from a Disney animated feature, as synonymous with Disney products as Mickey Mouse. Most prominently, a snippet of the song has accompanied the famous opening logo of Disney movies for decades.

6Harvey Fletcher

It is impossible to imagine a world without stereo sound. Everything from car speakers to headphones to movie sound systems use stereo presentation. We have become so accustomed to stereo sound systems that mono sounds flat and strange to modern ears. But that was the reality of audio recording until Harvey Fletcher’s tenure as Director of Physical Research at the Bell Telephone Laboratories. Fletcher’s parents were Mormon pioneers who migrated to Utah in the mid-1800s. Both had received minimal education and their son’s scientific prowess went unrecognized until he began attending school. Quickly completing his education, Fletcher moved to Chicago, where he received a PhD in physics. For his doctoral dissertation he worked with Robert Millikan to develop ways of finding the charge of electrons. Millikan took full credit for the work, which eventually won him a Nobel Prize. After a brief stint at Brigham Young University, Fletcher was recruited by Bell Laboratories. While working with telephone technology, Fletcher became interested in speech and perception, specifically how voices were distorted over telephone calls. By studying telephone distortion, Fletcher was able to develop better telephone technology. Producing correct and realistic sounds fascinated Fletcher and led to his interest in stereophonic sound. During a 1930s demonstration, Fletcher terrified his audience by making it sound like airplanes were flying around overhead. In the 1940s, he was able to transmit an orchestral performance from Philadelphia to Washington, DC, splitting the sound into three channels for realism. With the success of these tests, Fletcher had introduced the idea of stereoscopic sound to the public. These experiments also allowed Fletcher to develop the modern electric hearing aid. His hearing aid design changed the world for the hard of hearing and continues to be influential today. Fletcher continued his research well into his eighties. His love for science would prove extremely influential on his son, James.

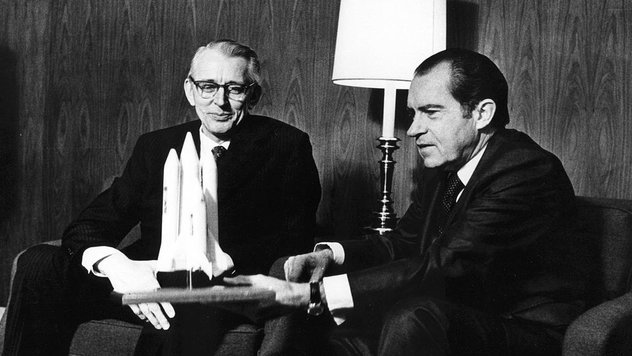

5James C. Fletcher

When Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon in July 1969, the golden era of space flight began. NASA already had a sizable lead over the Soviets when director Thomas O. Paine stepped down from his role as administrator in 1971. In his place, Richard Nixon appointed Harvey’s son, James Fletcher, who was then president of the University of Utah. Although the Apollo missions were successful, Fletcher faced growing public apathy and the difficult job of securing funding from Congress for future programs. However, the Skylab and Viking missions were already under development when he joined NASA and were successfully launched under his watch, demonstrating the relevance of NASA’s programs to politicians and the public. Fletcher also oversaw the Voyager space probe, but his biggest contribution was the space shuttle program. In the ’60s, Air Force and NASA engineers had proposed the idea of a reusable space vehicle, but President Nixon wasn’t sold on the idea. In a series of meetings in the early ’70s, Fletcher was able to convince Nixon to support the project by guaranteeing that the shuttle would be less costly in the long run than the Apollo missions. Although that prediction ended up being untrue, the shuttle program moved forward. Fletcher retired in 1977, just as the space shuttle program was beginning. However, disaster struck on January 28, 1986, when the space shuttle Challenger was destroyed at launch due to a faulty booster rocket. In response, Fletcher was pulled out of retirement and was reinstated as the administrator of NASA, becoming the only man to hold the position twice. On taking over, Fletcher put the shuttle program on hiatus and oversaw a complete redesign of the shuttle components. His leadership gave NASA some much-needed stability although Fletcher himself was caught up in fruitless conflict-of-interest investigations. He retired for good in 1989, shortly after approving the Hubble Space Telescope program.

4Sandy Petersen

Many people have been entranced by the works of horror legend H.P. Lovecraft, but few have done as much with their fascination as Sandy Petersen. He was first introduced to Lovecraft through a paperback his father owned, which prompted a lifelong love of fantasy novels and an interest in Dungeons & Dragons. At just 19, Petersen was hired to write supplements and new games for tabletop game company Chaosium. During his time at Chaosium, Petersen became the principal author of Call Of Cthulhu, one of the most iconic tabletop role-playing games of all time. While Dungeons & Dragons focused on combat, Petersen’s game explored the investigative and mystery potential of role-playing games. As such, the combat mechanics could be a little boring, but the emphasis on clues and riddles changed the way that role-playing games were written. It also became one of the main forces keeping H.P. Lovecraft’s works relevant to modern audiences. After Petersen’s success with Call Of Cthulhu, he became interested in the burgeoning field of video games, especially the early first-person shooter Wolfenstein 3D. After doing some work with Sid Meyer, Petersen was hired by id Software, who were in the process of completing the legendary game Doom. Petersen was able to create 20 levels for the game in 10 weeks. During this time, he also revised many of the designs for the monsters, creating some of the most iconic moments in the game. The success of Doom brought first-person shooters to mass audiences. Petersen also contributed heavily to the design of Doom 2 and Quake, before leaving for Ensemble Studios, where he helped design Age Of Empires, one of the most iconic real-time strategy games ever. Petersen was often asked if his Mormonism ever came in conflict with designing games full of demons and monsters. In an exchange with John Romero, Petersen joked: “I have no problems with the demons in the game. They’re just cartoons. And, anyway, they’re the bad guys.”

3Gary Kurtz

Although George Lucas receives most of the credit for Star Wars, fans of the series know that its success couldn’t have come about without the skills of producer Gary Kurtz. In the early 1970s, Kurtz and Lucas were both independent filmmakers working in California and first collaborated on the nostalgic teen movie American Graffiti. When that became a huge success, Lucas and Kurtz were able to begin work on their science fiction masterpiece, Star Wars. Originally intended as an homage to the Flash Gordon serials, the movie was hard to pitch to Fox executives. According to Kurtz, they were concerned that Star Wars was too difficult to understand and wouldn’t make enough money to justify the budget. But clever bargaining secured funding and the space epic moved forward. Once the pre-production started, the importance of Gary Kurtz’s talents as a producer can’t be overstated. He was responsible for arranging casting calls, worked to set up the Industrial Light & Magic production studios, and hired the sound engineers who gave Star Wars its distinctive sound effects. According to Kurtz, his role was to deal with the small details of making the film, allowing Lucas to focus on the big picture. Although the production was beset with problems, Star Wars became a huge hit that revolutionized modern cinema. Riding their success, Kurtz and Lucas began working on the sequel, tentatively titled Star War II: The Empire Strikes Back (the number was eventually changed to V). Empire‘s production saw an increase in Kurtz’s influence, as he began working personally with the actors, writing large chunks of the story, and even acting as a secondary director. When developing the concept of the Force, Lucas initially favored it emanating from a mysterious crystal, while Kurtz advocated the more universal and mystical description of the Force that was included in the movie. By the time Return Of The Jedi was in pre-production, Kurtz and Lucas were experiencing creative differences. Kurtz favored a darker version of the story, with Han Solo dying halfway through the movie and the rebellion ultimately failing. Lucas rejected these ideas and insisted on a story closer to what was filmed. Kurtz was also concerned that the story had become too much about selling toys and did not like the idea of having another Death Star. These differences ultimately led to Kurtz leaving the project. According to Mark Hamill, it was like mom and dad had broken up.

2John M. Browning

In 1840, a young justice of the peace named John Browning was fascinated by the Mormon settlement in Nauvoo, Illinois. On a trip through Nauvoo, John Browning met Mormon prophet Joseph Smith and was so impressed by the young religious leader that he joined the church, setting up a firearms shop in the city. When the Mormons were kicked out of Illinois, Browning migrated West and settled in Ogden, Utah. His son, John M. Browning, followed in his father’s footsteps, securing his first gun patent at the age of 24. His career would eventually revolutionize firearm technology. The younger Browning was originally interested in creating rapid-fire machine guns. In those days, machine guns were mechanically operated and had issues of speed and reliability. Browning’s breakthrough was to realize that the recoil caused by the bullet could be used to force the shell out of the gun and re-chamber another shell. While working for Winchester Colt, Browning designed the M1895, the first gas-operated machine gun in the world. With the patent secured, Browning was able to further investigate the possibilities of his design, creating machine guns that were used during World War I and World War II. Browning’s designs were iconic for their versatility and dependability. Most famous were the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) and M2 .50-caliber machine gun. The latter gun was used during World War II and is still in service with some armed forces. The gun was versatile enough to be used for everything from anti-aircraft defense to infantry support to aircraft-mounted weaponry. Aside from his machine guns, Browning also designed the iconic M1911 pistol, which was only recently phased out in American armed forces after almost a century of use. Browning spent his whole life designing firearms. In hindsight, the M1895 completely revolutionized warfare. Nearly all subsequent automatic rifles and machine guns have been gas-powered. The influence of Browning’s invention has changed the world, for better or for worse.

1Philo Farnsworth

To people outside the church, Philo Farnsworth is surely the most influential Mormon to ever live. Although relatively unknown today, Farnsworth invented the first fully electric modern television, which led to the modern idiot boxes that we all know and love. Farnsworth’s fascination with electricity started at an early age, when he converted all the appliances in his family’s house to run on electricity. By the time he was in high school, Farnsworth was already planning to create an electric television—he even showed early schematics to his chemistry teacher. After a brief stint at Brigham Young University, Farnsworth set up a laboratory in San Francisco and transmitted the first image using a fully electronic television in 1927. Newspapers breathlessly reported that Farnsworth’s TV was entirely based on electrical currents and “employs no moving parts whatever.” Farnsworth’s early television had extreme limitations. Since the tubes were illuminated by an arc lamp, the television had weak light sensitivity. In order to send any image, the subject of the transmission had to be illuminated by huge floodlights, causing great discomfort for the unfortunate subject, which was usually Farnsworth’s wife. The device was demonstrated publicly in 1928, immediately piquing the interest of electronics company RCA. In 1931, Farnsworth rejected an offer by RCA to buy his patents, preferring to work at the Philco company. RCA did not let the matter die, filing a patent interference lawsuit against Farnsworth for the electronic television. It was eventually decided that Farnsworth had not committed patent interference, but by that time various inventors had started using technology similar to Farnsworth’s early television designs. Embroiled in legal battles, Farnsworth left Philco, and RCA was eventually able to buy his patent for a cool $1 million. In later life, Farnsworth pursued other avenues of research in the fields of radar and milk sterilization. But his greatest accomplishment will always be the work he did in television. With his designs, RCA was able to corner the early market, making TV the household necessity it is today. Unfortunately, Farnsworth’s lifelong battles with depression led to heavy alcohol abuse in the 1970s. He died in relative obscurity but is now considered the father of television. Zachery Brasier is a physics student who writes on the side.