10 Marco Tulio Catizone

Dom Sebastian was the king of Portugal in the mid-16th century. When he was killed on a Crusade, rumors spread that he would one day return to his country to free them from Spanish oppression. In 1598, it seemed that the prophecy had come true. The “king” had been arrested in Venice after having wandered Europe in penance for his defeat in the Crusades. Portuguese nobleman Dom Joao de Castro, convinced that this king was real, secured the man’s release from prison. But the man was arrested again in Naples. When questioned, he admitted that he was an ordinary man named Marco Tulio Catizone. By 1602, he had been sentenced to spend the rest of his life in the king’s galleys. The next year, he was tried again for inciting a rebellion. Even as de Castro petitioned on behalf of the man he still believed to be king, Catizone confessed his true identity again and was hanged in September 1603.

9 Basil The Copper Hand

In the 10th century, Byzantium was rocked by a series of peasant uprisings when countless people were starving. In 932, one uprising was led by nobleman Constantine Doukas, which was impressive because he had been beheaded in 913 after a failed attempt to seize power. The man masquerading as Constantine during the Bithynia uprising was actually named Basil. He earned his epithet, “The Copper Hand,” when his deception was discovered, his hand was cut off, and he replaced the appendage with a copper version. Even so, the impostor headed back to Bithynia to rally the poor and the starving again. Ultimately, he was captured, sent to Constantinople, and executed.

8 Mary Carleton

In 1663, a German princess met and married a nobleman living in London. After the wedding, the truth started to come out that the “German princess” was a woman named Mary Moders who had been born in Canterbury around 1634. Married first to a shoemaker and then a second time in Dover, she escaped bigamy charges, fled to London, and assumed the identity of German royalty. There, she met John Carleton, a law student whose well-to-do family allowed him to put on the illusion of nobility to win her hand. Mary was put on trial for bigamy. But when her previous husband did not appear, she walked free. Ironically, she went on to play the same part in a stage play called The German Princess. Seven years later, she was convicted of theft and sent to Jamaica. She later escaped, only to be recaptured and hanged.

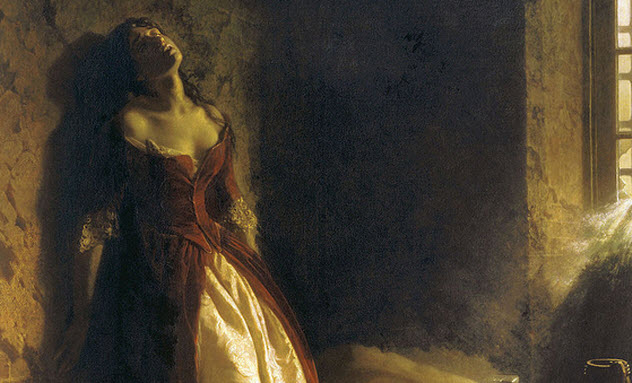

7 Princess Tarakanova

In the 1770s, word reached Russia’s Catherine the Great that a new princess had appeared in Europe. Catherine ordered the Russian fleet to take the young woman to Saint Petersburg, where she was sequestered in Peter and Paul Fortress. The stately young girl with dark hair had an Italian profile and a cough that suggested tuberculosis. When she was questioned by Catherine’s officers, the so-called Princess Tarakanova told a life story that was more akin to a fairy tale. But the servants who traveled with her were convinced of her royal identity. The princess refused to change her story even when more and more basic comforts were taken away. Amid reports that she was actually the daughter of a tavern keeper from Poland, she grew increasingly ill. Left in her bare cell, she died in December 1775. No one has ever discovered her real name.

6 Michael Ely

During the Napoleonic Wars, the HMS Audacious captured the French man-of-war Genereux. Each crew member of the Audacious was entitled to a share of the government prize money in the amount of one pound, 12 shillings. Crewman Murty Ryan presented himself to the designated authorities and collected his prize. Unfortunately, the agent handing out the money knew that the man standing before him was Michael Ely, not Murty Ryan. But Ely claimed that he had simply changed his name since the last time he and the agent had met. Despite the agent’s misgivings, he paid Ely. Later, the real Murty Ryan showed up to claim his reward. The case went to the Old Bailey, and witnesses testified to Ely’s deception on February 16, 1803. Ely was found guilty of the crime of “personation” and was sentenced to death.

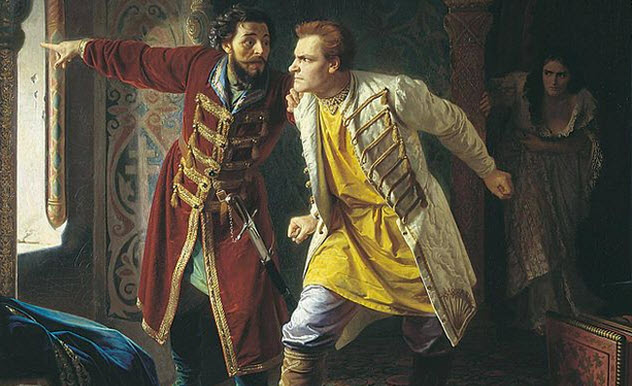

5 The False Dmitry

Three different men claimed to be Dmitry, the youngest son of Russia’s Ivan the Terrible. The first actually ruled from July 1605 to May 1606. He had the support of a major section of Russia’s nobility even though he looked nothing like the real Tsarevich Dmitry. But when it was rumored that he intended to reunite the Catholic Church and the Russian Orthodox Church, he was overthrown. The other two impostors each claimed to be the first Dmitry by saying that they had survived the coup. One added some believability to his story by contending that he had been tortured into admitting that he was Dmitry. He never assumed a position of power, but he was assassinated. The third Dmitry showed up a year later and gained some support. However, he was removed by the Russian government and executed before he could seize power.

4 Gaumata

Gaumata was a pretender at the heart of one of the most hotly contested successions in ancient history: the transfer of power to Persia’s Darius I. The official version written by Darius says that the confusion started when Cambyses, son of Cyrus the Great, murdered his half brother Bardiya. When someone claiming to be Bardiya later showed up at the head of an army, it was clear that he was an impostor. His name was Gaumata, and when Cambyses died, the impostor and usurper took control. Darius gained widespread support and overthrew the usurper, who was ultimately killed in Nisaya. After taking power himself, Darius used his murdered predecessor’s true identity as extra justification for his own actions. But it remains unclear just who died to turn the throne over to the man who became one of Persia’s most powerful kings.

3 Ralph Wulford

Ralph Wulford, the son of a shoemaker, lived in southeast England at the end of the 15th century. Under the guidance of a particularly resourceful monk, Wulford (sometimes spelled “Wilford”) was able to assume the guise, personality, language, and bearing of the Earl of Warwick. As the earl, Wulford was used by the monk as a sort of rallying point for the people of Kent. At the time, the nation was not far removed from the War of the Roses, and the monarchy was ever on the lookout for traces of a Yorkist uprising. The monk’s efforts to stir the support of the people ended in his arrest and life imprisonment and the hanging of his star pupil. Historical record is unclear on whether the plan had any success in raising Yorkist sympathies.

2 Gabriel de Espinosa

When Spanish rule came to Portugal after the death of Sebastian in 1578, several plots were hatched to put the country back in Portuguese hands—even if those hands belonged to a baker. In 1594, the members of an Augustinian convent—which included the niece of Philip II, Portugal’s Spanish ruler—were being convinced that Sebastian had returned to them. In a plan likely devised by the convent’s vicar, Gabriel de Espinosa took on the role of the dead king to forge an alliance with Philip II’s niece and ultimately restore Portugal’s independence. Even when de Espinosa was facing the gallows for his deception, he refused to admit that he was not the king. His dignified bearing as he was led to his death only added credence to the rumor that he was, really, the king.

1 John Deydras

One strange day in 1318, an odd man showed up at Beaumont Palace during the reign of Edward II and asked for the keys to the royal seat. He got arrested instead. Raised as John Deydras, he claimed that he was the real Edward II and had lived at Beaumont Castle as a boy. But a pig had bitten off his ear one day while he was playing in the yard, so his nurse had switched him with the son of a local carter rather than take responsibility for damaging the prince. Deydras wanted to face Edward in single combat. When the king offered him a position in his court as a jester, Deydras had a bit of a meltdown and was sent to prison. There, he confessed that he had made up the entire story after his pet cat—who was the Devil, of course—had given him the idea. Both the man and the cat were hanged. Read More: Twitter