But in the early days of the United States, many parties with different ideas rose and fell depending on the political situation and the burning issues of the day. Despite never achieving great national power and influence, some parties still applied enough political pressure to force key changes to the nation that can still be felt today. Here, we explore the histories of 10 influential political parties that disappeared.

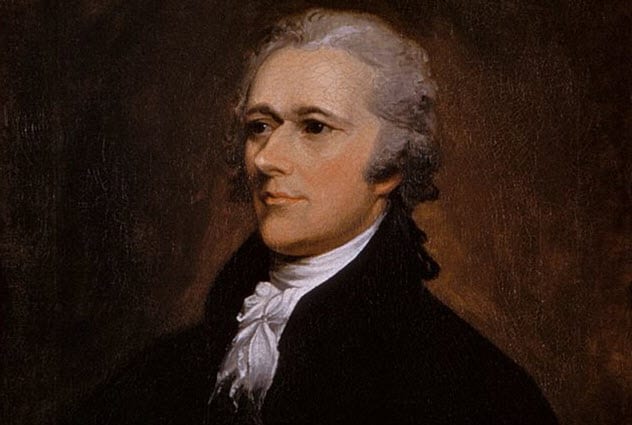

10 Federalist Party

The Federalist Party grew out of Alexander Hamilton’s desire for America to have a strong, central government. Facing opposition in Congress, Hamilton embarked on a campaign to win public support. He wrote 81 public essays and toured the country giving speeches in favor of his ideas or opposing the plan for a decentralized union of independent states that his enemy, Thomas Jefferson, favored. By 1791, newspapers were beginning to call Hamilton’s supporters “Federalists.” The party’s support was largely based in the Northern states. They relied on industry and trade for their livelihoods and so were more open to Hamilton’s plans for a strong government with a central bank and state debt. The party was not as popular in the South, where people were less enthusiastic about the union and more likely to want sovereign power for their state. This issue would boil over into civil war in the 1860s. The party was a strong advocate of friendly relations with Great Britain and opposition to the French Revolution. The party fundamentally shaped the modern United States by passing the Constitution, assuming the debts of individual states as a single national debt owed by the federal government, and setting out the powers of the president and his administration. Things changed quickly, however, as the Federalists passed the Sedition Act in 1798, which banned newspapers from publishing anything overly critical of government figures. The election of 1800 was hard-fought with tensions high on both sides, but Jefferson and his new Democratic-Republican Party narrowly won. The Federalists returned to power in Congress following the disastrous War of 1812 but never again had any significant influence in US politics.[1]

9 Know-Nothing Party

In the 1830s and ’40s, the United States experienced a surge in immigration from Ireland, Germany, and other Catholic communities primarily in Europe. Some Americans were alarmed at the growth and worried that it would lead to a Catholic takeover of the country. In response, Charles B. Allen formed a secret society known as the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner in 1849. Its primary purpose was to oppose the new immigrants and the government’s immigration policy. Members were expected to be native-born Americans, Protestants, and at least 21 years old. If anyone asked them about the party, they had to reply by saying they knew nothing, which eventually became the group’s nickname. Popularity for the movement grew over the course of the 1850s, and by December 1855, 43 Congressmen were also members of the group. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, passed in 1854, drove antislavery Republicans and proslavery Democrats away from their old parties to the Know Nothings as a kind of protest vote. Buoyed by their success, the Know Nothings went public and formed an official party, the American Party. They were already past the peak of their power, though. Despite running a candidate for president in the 1856 election, the party’s support had largely fallen away by the following year. Ultimately, the US public forgot about the immigration threat as slavery became more of an issue and the Civil War loomed. By 1860, the party was no more.[2]

8 Democratic-Republican Party

Originally formed as the Republican Party by Thomas Jefferson in 1792, the Democratic-Republicans were comprised of those who opposed the Federalists’ plans for a strong national government. At their core, the Democratic-Republicans were anti-elite and anti-monarchy. They chose the name Republican to emphasize their support for the French Revolution and opposition to royal rule of any kind. They protected the rights of the poor against the excesses of the rich and argued that individual states should have the power to govern their land how they saw fit. Following their victory in the 1800 election, the Democratic-Republicans remained in power for another 20 years. By this time, though, they were more a coalition of different interest groups than a single political party with a set objective. The party eventually splintered after the election of 1824, in which different members of the party backed four different presidential candidates. The victors, led by Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, formed the National Republican Party. The loser, Andrew Jackson, dropped the word “Republican,” and they became the Democratic Party that exists to this day.[3]

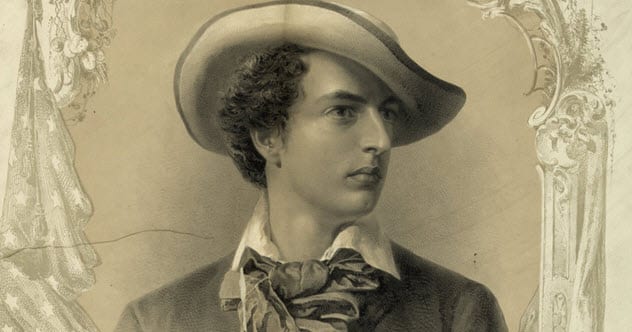

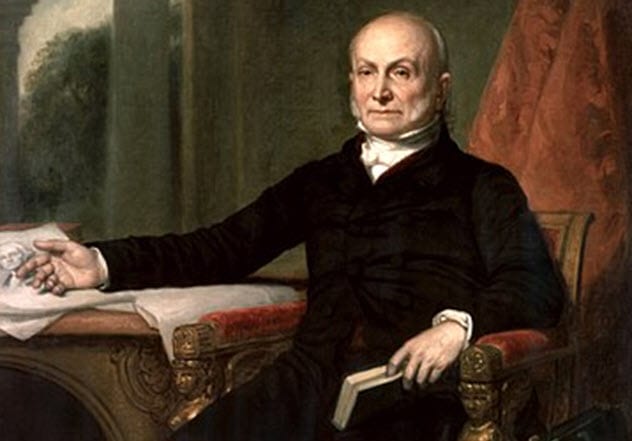

7 National Republican Party

The National Republican Party was formed by the followers of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay after Adams won the presidency in 1824. They had an ambitious plan to overhaul US infrastructure, which included building a national road from Washington to New Orleans and establishing a national university and naval academy. Their plan was to raise cash for the treasury by selling land in the West to private buyers, thereby pursuing government projects without having to raise taxes. Primarily, the focus was on upgrading and repairing roads and other connections to link the nation and make people more patriotic toward the nation as a whole rather than the state in which they lived. During Adams’s presidency, many canals were built across the United States as was the first passenger train. His whole term in power was marred by Andrew Jackson’s Democrats, who argued that Adams and Clay had worked together to win the presidency in a “corrupt deal.” This argument won widespread support among the people. As such, Congress refused to pass many of his policies, and the National Republicans had accomplished very little by the time they were crushed in the 1828 election, never to hold power again. They contested the 1832 election but were roundly defeated once again. The party collapsed, with many of its members helping to form the Whig Party.[4]

6 Anti-Masonic Party

In 1826, William Morgan, an ex-Freemason, went missing. Some months before his disappearance, he went public with his hate for the Freemasons and announced that he planned to publish a book exposing all their secrets. He was arrested and vanished shortly afterward. No trace of him has been found since. Many Americans believed that he’d been murdered by the Freemasons to prevent their secrets from getting out. In 1828, a group of journalists and other enemies of the Freemasons came together and formed the Anti-Masonic Party. Their argument was that the Freemasons, as a secret society, went against the republican traditions of the United States and posed a threat to individual liberty—especially since many members of the National Republican government were also Freemasons. They experienced unexpected success in the 1828 elections in which they became the first-ever third party to win seats in Congress. In the run-up to the 1832 election, they also hosted the first presidential nominating convention in US history when they chose William Wirt as their candidate for the presidency. All other major parties have used the convention system to nominate presidential candidates since. The Anti-Masons fell apart after their convention failed to nominate a candidate for the 1836 election. Many of its former members joined the anti-Jackson Whig Party shortly after.[5]

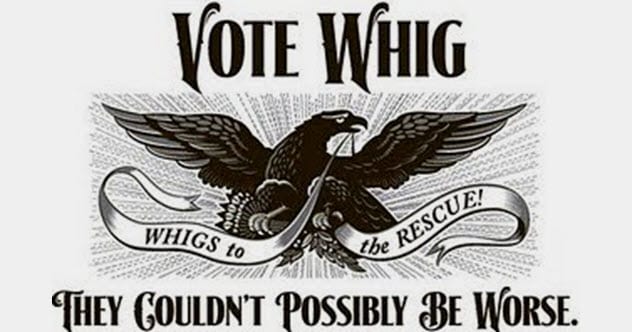

5 Whig Party

Andrew Jackson was a divisive president. During his two terms, he drove Native Americans off their lands, made up lies to smear his political enemies, and dismantled the Bank of the United States. He was also the first president to suffer an assassination attempt. Many accused him of abusing his power and ruling like a dictator, giving him the nickname “King Andrew.” His enemies tried to reinforce that image by joining together and forming the Whig party—named after the famous Whig party in Great Britain which opposed the powers of the monarch. Over the 30 years of the party’s existence, it developed into something more than a coalition of people who hated Jackson and even had four presidents. The party found much of its support among the growing US middle class and urban population.[6] They supported the party’s pro-business and pro-industrialization policies which dramatically increased the nation’s wealth. Others were attracted by their support of the rule of law and opposition to extensive presidential power. Ultimately, the Whigs were toppled by the rise of the biggest issue to ever dominate US politics: slavery. Some in the party, the Cotton Whigs, supported the Southern states, while the Conscience Whigs supported the Union. When the Civil War hit, many Conscience Whigs, including Abraham Lincoln, joined the newly formed Republican Party, while their opponents joined the ranks of the Democrats.

4 Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived but very influential movement that sprang out of the slavery debate in 1848. They quickly became popular after their formation and nominated the former president, Martin Van Buren, for reelection. They were a single-issue party dedicated to preventing the expansion of slavery to the newly formed Western states. Their slogan—Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, Free Men—was later adopted by the Republican Party after they took a strong antislavery stance, which was largely motivated by the success of Free Soil. Though they never achieved outright power, they were an influential third party in the election of 1848, receiving 300,000 votes. More importantly, they drew votes away from the proslavery Democrats, giving the Whig candidate the presidency and resisting the expansion of slavery to the West. They won local power in some of the Northern states and passed laws preventing discrimination against free African Americans. Their most important legacy, however, was their alliance with elements of the Whig Party in August 1854, forming the modern-day Republican Party.[7]

3 Readjuster Party

The Readjuster Party—the most successful political party you’ve never heard of—was a regional party that operated in Virginia between 1879 and 1885. Founded as a single-issue party whose main goal was to settle Virginia’s debt problems, it came to dominate Virginia politics before it was dismantled by a targeted Democratic campaign. Many of its members left to join the Republicans. The state of Virginia had racked up $45 million in debt by the conclusion of the Civil War, so much that the state was struggling to raise cash. Problems were exacerbated by the decision in 1871 to issue bonds in the hope of stimulating the state’s economy. Annual interest for bondholders was set at 6 percent. Payment of interest on the bonds took up over half the state’s annual revenue. Some years later, in 1878, Virginia’s General Assembly passed a bill to collect more revenue in cash rather than coupons to fund the public school system. When the state’s governor vetoed it, the Readjuster Party was born, promising to reduce the amount of interest paid on bonds. The party quickly grew very popular, particularly because of its Reconstruction-era approach of including both black and white people in the party. It won majorities in both Houses in 1879 and, by 1881, had also won the election for governor. In 1882, they’d reduced the bond interest payments to 3 percent. Flush with cash, the new government reduced taxes on farms, small businesses, and other areas of society who’d carried most of the weight of the debt repayments. They increased taxes on big corporations, while doubling the funding for public schools. They overhauled the higher education system and, by 1883, had turned the state’s crippling deficit into a surplus. Most stunningly, they were able to pass many reforms that advanced the rights of African Americans. They founded the first college dedicated to training black teachers, abolished the whipping post as a form of punishment for African Americans, and abolished the poll tax as a prerequisite for voting. This enfranchised thousands of black Americans. Due to these actions, the town of Danville elected a black-majority council which led to the establishment of an integrated, multiracial police force. Their progressive policies proved to be their undoing. The Democrats tapped into the racial anger felt by many of the state’s white landowners and sharecroppers by arguing that the Readjusters were enabling African-American racial superiority. The message cut through, and in 1885, the Democrats took back all statewide offices. What was left of the Readjuster Party was absorbed by the Republicans.[8]

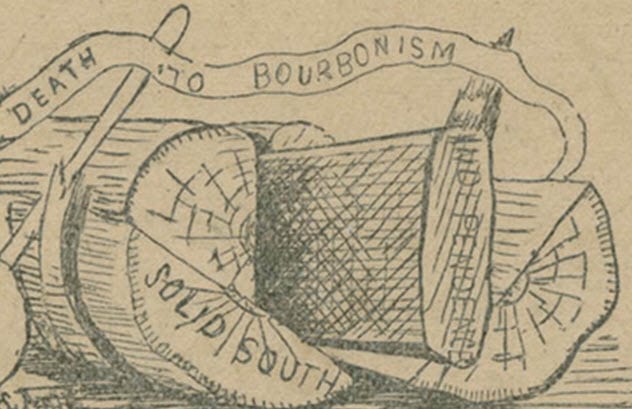

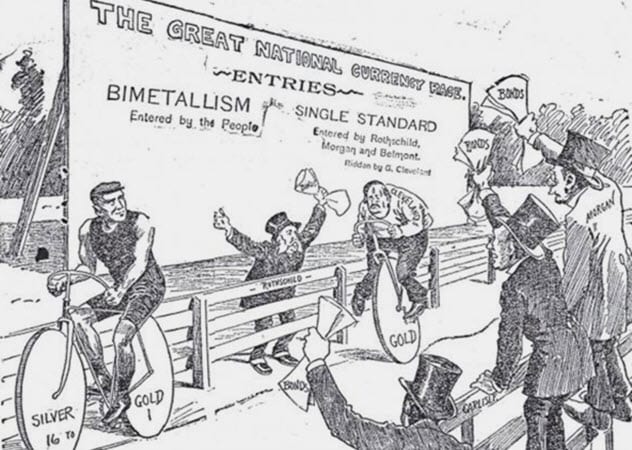

2 Silver Party

In 1873, the US economy collapsed. This crash was known as the Panic of ‘73, and it added fuel to a debate over US monetary policy that had been raging since the end of the Civil War. Many people across the country, including the Democrats and Republicans, supported the relatively new idea of the gold standard. They believed that it would give people more faith in the currency. Others still believed in the newfangled bills issued by the government to raise money during the war. These people joined the Greenback Party. The main opposition to the gold standard, however, came from the Free Silver Movement, which drew its support from many people across the Midwest and Western states. These people backed a bimetal system, where the currency was valued against both gold and silver, with two main sets of coinage. Nevada was a natural home for the Free Silver Movement because it produced much of the nation’s silver and many of the new state’s people worked in the silver industry in some way. Politicians from the Silver Party held influence in Nevada from 1892 to 1911, during which time the wider movement earned concessions from the government. At one point, the government even agreed to buy lump sums of silver from the producers. Public support and Silver Party lobbying led to the Democratic Party adopting the free silver issue for the 1896 election. Their influence was not to last, however, and the Republican Party put the dreams of a bimetal currency to bed in 1900 when they passed the Gold Standard Act. Voters continued to back the Silver Party in Nevada for another decade, by which time the cause for free silver had become generally associated with supporting the needs of the poor over the needs of the rich. This concept maintained the Silver Party’s support after the rest of the movement died out. But the party had faltered by 1902 and associated itself with the Democratic Party thereafter. It was officially dissolved in 1911.[9]

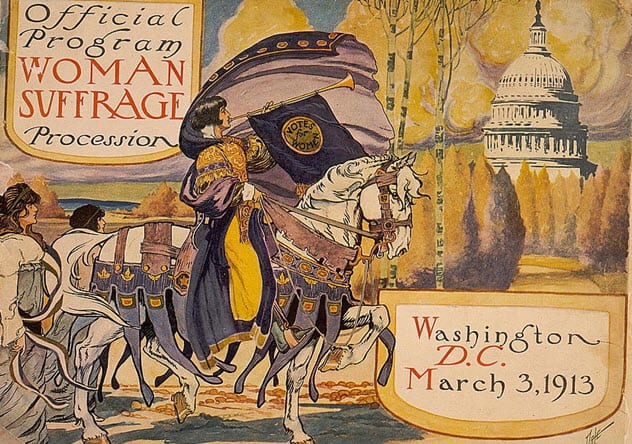

1 National Woman’s Party

The National Woman’s Party was created by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns in 1913 as the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. The pair had spent time in Britain in their youth. While she was a student, Paul got to know Emmeline Pankhurst and her suffragettes. The suffragettes were famous for employing extreme measures, including resorting to crimes like arson, to try to win equal voting rights for women. In 1916, Paul and Burns renamed their party and agreed to adopt similar measures in their own efforts to secure the vote. In January 1917, this came to a head when members of the National Woman’s Party began to picket the White House after a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson. Unlike their allies in Britain, the National Woman’s Party continued to protest throughout World War I, which dented their public support. But their methods were effective. Alongside their highly public picketing and marches, the Suffragist magazine they produced did much to publicize both their mission and the brutal measures the police sometimes used against them. In 1919, President Wilson went in person to Congress and urged them to pass the Nineteenth Amendment. In 1920, the bill was passed and the women’s picket of the White House ended. After this, they turned their efforts to trying to pass the Equal Rights Bill. While this goal was never achieved (the bill still hasn’t been passed even today), they were successful in pushing for other equal rights, such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963.[10]