Artists’ dollhouses comment upon the human condition. They bolster girls’ self-confidence as they acquaint them with science, technology, engineering, and math. They amuse. They test university students’ knowledge and ability. They remind the public about the seamier side of life back in the day.

10 Homicide Houses

Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962) developed a keen interest in crime scene investigation. Putting her fortune as an heiress to work, she created dollhouse dioramas of crime scenes to help detectives develop investigative techniques. During parties at her splendid mansion, she learned from her guests—police investigators—the details of their profession. Even today, her dollhouse dioramas provide a means of preserving the semblance of actual crime scenes so investigators, in examining them, can detect clues that help them to solve crimes. She called her homicide houses “The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.” With her dollhouse dioramas before them, detectives learn to study a room for evidence so they can piece together the events of the crime. Investigators learn how to use search patterns to completely and thoroughly search the scene of the crime. Her Nutshell Studies helped train detectives in Chicago. In Maryland, they are used to this day to help train investigators in crime scene analysis. One dollhouse diorama, a bathroom with pink marble fixtures and pink trim, is the scene of a woman’s murder. The doll representing her lies on its back, wearing a robe, its arms at its sides. The figure is reflected in the full-length mirror on the inside of the partly open door. She has suffered a wound to her neck, which is embedded with fibers. Near the body at the foot of the tub, a white stool stands. Wainscot divides the walls. The upper portions are covered in floral wallpaper; the lower portions are painted white. A pink-and-white bath towel is draped over the side of the marble tub, and pink towels hang from a bar on the wall at the head of the tub. White hand towels hang from a bar extending from the rear wall to the left of the marble sink. A mirror occupies the same wall above the sink. To the right of the sink, the toilet stands in the corner of the room, followed by a toilet tissue holder, a hot-water radiator, a bathroom scale, and a vanity set with toiletries along the right wall. A window above the radiator is framed by pink drapes, drawn and gathered at the sides and held in place by floral ribbons. An oval, beige throw rug edged with pink fringe occupies the center of the room. The woman’s slippers are at the edge of the rug nearest the bathtub. A strand of fibers is draped over the inside top of the door. Like all of Lee’s dollhouse dioramas, this one is based on an actual crime. Its numerous details are not only realistic but also sufficient to challenge detectives’ analytical and deductive abilities. From inspecting this crime scene, detectives might be expected to observe that there are “no signs of forced entry.” In addition, they should detect the “small threads hanging from the door” and perceive that they “match the fibers found in the wound around the dead woman’s neck.” As a result, they should be able to solve the crime by drawing the conclusion that her death is the result of suicide. She “used the stool to hang herself from the bathroom door.”

9 Historical Houses

The dollhouses on display in 2016 in the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, don’t teach detectives how to analyze crime scenes, but they do have educational value. In a sense, they’re interactive time capsules. Each house represents a period of residential architecture from bygone days. In addition, recorded messages enlighten visitors about the times in which people lived in the actual versions of these houses. Called “Small Stories: At Home in a Dollhouse,” the exhibit featured a dozen dollhouses on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. One of the dollhouses, a replica of an elegant 1760 townhouse, includes a mother’s lecture to her daughter, available at the push of a button, about “the proper way to run a home.” An 1830 dollhouse was a gift to “the wife and five daughters” of John Killer. The dollhouse teaches about a problem that many faced at the time. Visitors who press a button learn from a bit of recorded dialogue that the purpose of the family’s cat was “to keep the rats away.” In giving his family the present, it seems that Killer might have had an ulterior motive. According to Alice Sage, a museum curator, it is likely that the ladies of the house “learned a few lessons” concerning “the management of a home” while playing with the dollhouse. The last exhibit is a timely one indeed, focusing on tiny spaces if not tiny houses. At the request of the museum, two dozen American “artists, designers, and architects” each designed his or her “dream room.” The rooms could relate to “the past, present, or future.” One room, a boudoir, was even “created with a 3-D printer!”

8 Banana Bark Houses

Historian and artist Veronica “Ronnie” Chameau was among the honorees on Queen Elizabeth’s 2016 annual Birthday Honors List. Chameau received the British Empire Medal for promoting Bermuda’s heritage and culture. Her artwork celebrates local culture, making use of Bermuda’s natural resources. Her construction materials are derived from the bounty of the island’s “banana and palm leaves, nuts, seedpods,” and flowers. She uses them to create “tree ornaments, musical angels, and nativity scenes.” Oh, yes, and dollhouses! More specifically, Chameau uses banana tree bark to create her dollhouses. Her replica of Verdmont, Bermuda’s Georgia-style mansion from the early 1700s, is displayed in the garret of the National Trust Museum in Smith’s Parish. Her dolls are also exhibited by the Smithsonian Archives in Washington, DC, and by The Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut.

7 Royal Dollhouse

The dollhouse built by architect Edwin Lutyens is truly a residence fit for a princess. In fact, it was designed by a princess—and by the architect she hired to construct it. In his day, Lutyens was one of the most celebrated architects in the world, his work respected and lauded by Frank Lloyd Wright. Lutyens’s forte was designing elegant country houses. When Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, Princess Marie Louise, asked Lutyens to build her a “massive dollhouse” as a present for her cousin Queen Mary, they discussed the details of its design “over glasses of champagne.” Three years later, after a crew of 1,500 workers, including “artists, craftsmen, gardeners, and even vintners,” concluded their labors, the result was Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, completed in 1924, just in time for display at the 1924–25 British Empire Exhibition. At 1.5 meters (5 ft) tall, it was constructed on a scale of 2.5 centimeters (1 in) equals 0.30 meters (1 ft) and included a working miniature gramophone, sinks supplied with hot and cold water, and a library stocked with “hundreds of tiny books (many written by prominent British authors specially for the library).” There was even a wine cellar containing “tiny bottles of wine.”

6 Gravesite Houses

What seems to be a tiny brick child’s playhouse—complete with chimney, window awnings, and a wreath on the door—in a landscaped yard surrounded by a low wall is really the final resting place of four-year-old Nadine Earles of Lanett, Alabama. The mausoleum in Oakwood Cemetery attracts many visitors. Intended as a Christmas gift, it became Nadine’s burial place when the sick child died. The house is full of toys, and Nadine’s parents are buried in the playhouse’s “yard,” with headstones marking their plots. A full-size playhouse mausoleum is unusual, but there are several dollhouse gravesites throughout the United States. The one in Medina, Tennessee, memorializes five-year-old Dorothy Marie Harvey. The white frame house with the red tin roof is filled with toys and maintained by the local community. Five-year-old Lova Cline’s grave in Arlington, Indiana, is topped by a white frame, Victorian-style dollhouse built by her father. Visible through the open windows, baskets of flowers, miniature furniture, a doll, and other toys sit atop the wall-to-wall carpeting. Her parents are interred in the house’s “front yard,” headstones identifying their graves. The Cornersville, Indiana, dollhouse atop seven-year-old Vivian May Allison’s final resting place is also of Victorian design, painted gray with green trim and a green roof. Inside the house, a doll, a bed, a dresser, a wall mirror, window drapes, a stove, and other miniature furniture and toys are arranged on the wall-to-wall blue carpet. For a century, a dollhouse memorial also occupied the gravesite of 12-year-old Lizzie Eckel. But sadly, vandals destroyed it in 1982, and it is now marked by a stone pillar. The dollhouse itself is memorialized in an article in the 1958 edition of the Milwaukee Journal.

5 Artist’s Houses

Single-handedly, British artist Rachel Whiteread has assembled an entire village! A village of dollhouses. Illuminated dollhouses. Dollhouses intended to make a statement. Whiteread has added 201 dollhouses to her collection throughout the years. The village’s houses are ironic, says the exhibition’s curator, Cheryl Brutvan. The “intimacy” of the lighted houses contrasts sharply with their “emptiness” since the houses are unfurnished. This contrast, she believes, highlights the nature of the “human condition.” In this sense, the collection makes the ordinary residences seem extraordinary. The houses rest atop the containers they came in, creating the appearance that they sit atop terraces of hills. The exhibit at The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is complemented by displays of Whiteread’s “sketches, studies, and collages” related to the village of dollhouses exhibit.

4 DIY Houses

To promote girls’ interest in science and technology, Stanford alumnae have created do-it-yourself dollhouses. Alice Brooks, Bettina Chen, and Jennifer Kessler realized that their own interest in the male-dominated fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) was due to their girlhood experiences. For example, Brooks asked her father for a Barbie doll. Instead, her father gave her a saw. She used her gift to build her own dollhouse which, she says, made her want to pursue a career in mechanical engineering. Like her fellow graduates, Brooks believes that giving young girls the chance to “design, build, decorate, and wire” their own dollhouses can provide them with a chance to learn to love STEM as much as Brooks, Chen, and Kessler do. The result of their efforts is Roominate, a company that integrates users (girls who want to build their own dollhouses) and online communication capabilities. Customers can share ideas, seek and offer advice, and access applications associated with the dollhouse materials they use to construct their dream houses. The dollhouse kits are “modular,” allowing users to arrange and rearrange shapes as they configure and shape their own dollhouses. The kits’ “motors, lights, fans, [and] circuits [demonstrate] basic engineering concepts.” Often, girls use their kits to build structures other than dollhouses, such as “elevators, rocket ships, [and] even a model of the Golden Gate Bridge, [complete] with working lights.”

3 Rat-Infested House

When a rat began to visit her dollhouse, Erin Hennessy took the opportunity to enter show business. She videotaped the trespasser and shared the result online as The Mouse Show live from Dartmouth. Instead of calling an exterminator, Hennessy moved the dollhouse into her shed, encouraging the rat to continue its visits by stocking dollhouse crevices with chocolate chips. She said she got the idea from another show in Norway which features birds eating from a feeder decked out as a bar. By all accounts, her show is a success. However, it may be canceled. Hennessy thinks she may call in the exterminators after all. “[It’s] irresponsible,” she says, to let the rodent make itself at home in her dollhouse even if it is now installed in her shed.

2 Haunted House

When a university professor is imaginative in creating class assignments, the results can be terrifying, as students in Dr. Ken Kaiser’s electrical engineering course at Kettering University found out. In fact, it was they who created the special effects to make regular dollhouses appear to be haunted. From outside, the Victorian house looks spooky enough. The house number is eerie and inexplicable: 252823. It also contrasts with the house number posted on the back of the house. Many spooky signs indicate the place may well be haunted: broken window frames and panes of glass, a boarded-up window on the first floor, blood splatter over the frame of a second-story window, bent pickets in the fence surrounding the front yard, a dead tree, and a human skull atop one of the gateposts. For good reason, there’s no welcome mat on the front porch. The unfenced backyard is just as forbidding. Huge cobwebs hang among the steep roof’s gables. Crime scene tape bars the porch. Unraveled, it also ensnares the shrub to the right of the rear entrance. A tree on the other side of the house threatens to engulf the residence. A headstone warns, “You are NOT alone.” The small cemetery to the right of the walkway indicates the truth of this advisory. But inside the house is where the true terrors await. Among other things for the summer 2015 project, one team of students used “spinning saw blades,” included a room on fire, and featured zombies peering into windows. They also created the spooky sound track for the project. To accomplish these feats, they had to “synchronize 6–8 mechanical actions inside the haunted dollhouses.” Austin Pollitz, Charlie Bierstetel, and Robin Trachsel used fishing line to connect a miniature figure’s rocking chair to a servomechanism so that the chair seems to rock by itself. The same technique opens and closes the bloodstained front door, rotates a bookshelf, and operates several of the automated house’s other special effects. This creates the appearance that they are moving by themselves (or perhaps being moved by invisible spirits). To lift the miniature house, the students employed “high-torque motors with gear rails at each corner.” They estimate they spent 200 hours on the project. At $30 per hour, labor costs alone would have totaled $6,000. The cost of materials was $485.48. Another team consisting of Alex Medina, Rebecca Mikolajczyk, Christian Pavkovich, and Mike Reed designed an even more elaborate haunted house. Lights flash on and off. A front door with an axe embedded in its exterior swings open to reveal a hanging bride in the doorway. The door then closes. The shadow of a woman operating a chain saw moves against the wall behind her. A glowing baby’s head revolves in an octagonal window above the house’s front entrance. An empty chair rocks back and forth. The hanging groom drops down from a ceiling. A servomechanism operates each of these mechanical actions. In addition, the haunted house uses electrical circuits and wires to power these effects. This team’s estimate for its work is even higher than that of some of its peers. The team spent 450 hours on the project, and materials cost $880—for a whopping total cost of $14,380! In either case, considering these prices, perhaps one of the Stanford graduates’ DIY houses would be a wiser use of money for those of us on a budget.

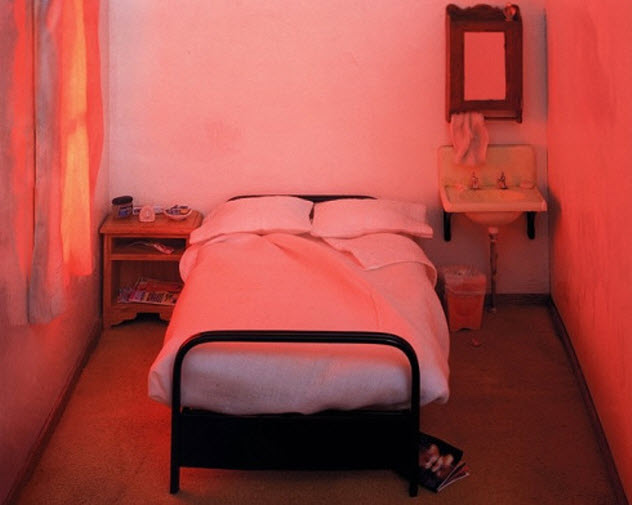

1 Brothel House

Artist Leanne Eisen faced a problem when it came to constructing her miniature brothel dollhouse. “Strip club stages, condoms, porn magazines, and sex toys” in one-twelfth scale were unavailable. She solved the problem by creating them herself. Using a variety of materials, she also created the rooms. She “modeled most [of her] dollhouses after small, Nevada-style brothels at the cusp of legalization,” but she also turned to many other forms of research, including “films, documentaries, book, [and] photographs.” Photographs of her brothel dollhouse’s rooms make up a series called Play. Her work has attracted so much attention that she is building upon it. Her latest addition to her series is a blue bedroom. In one of the series, a paneled hallway lined on one side with a variety of cast-off boots and high-heeled shoes leads into a sumptuous, red-carpeted room furnished with an elegant red velvet sofa. In front of the sofa, a walnut coffee table—matched by an end table of the same substance, style, and stain—stands across from a wingback chair. The end table holds an elaborate silver clock. A golden cupid adorns the wall. Beside him, a portrait of a lovely, kneeling, nude woman hangs, head back in apparent ecstasy, as she tosses her hair with her hands. A golden statue occupies the coffee table. If a man has to be shot by an arrow, it might as well be in opulent surroundings. Gary Pullman lives south of Area 51 which, according to his family and friends, explains “a lot.” His urban fantasy novel, A Whole World Full of Hurt, will be published soon by The Wild Rose Press. He writes several blogs, one of which is bit Lit: Short Stories Anesthetized, Euthanized, and Sterilized.