10 William Parry

During the reign of Elizabeth I, being a Catholic was a dangerous thing. Many Catholics fled to the continent, and William Parry was sent to spy on them. He sent regular reports back to London, telling his queen who was harmless and who might be plotting against her from the relative safety of Paris. His troubles began in 1580 when he was put on trial for allegedly assaulting a moneylender. The queen pardoned him from execution, but he was unable to sustain the lifestyle to which he had become accustomed. By 1583, he had decided to play both sides and wrote to a Roman cardinal of his intentions to serve the Catholic Church. It was not a wise life choice. In 1585, Parry was hanged, drawn, and quartered for his part in a plot to kill the queen.

9 Isabella Hoppringle

Isabella Hoppringle was the 16th-century prioress of the convent at Coldstream, which sat on the border between England and Scotland. At the same time that she relied on the Scots to keep her convent safe, she was writing letters to agents of Henry VIII reporting on the Scottish army. Her favored position with Scotland’s queen, Margaret, meant that Isabella was often in Glasgow and Stirling and that she was witness to troops being mustered and equipped. In 1523, the Lords of Council decided that the punishment for talking to the English would be the death penalty, and word had gotten out about the prioress’s messages. It was only when Margaret interceded that the lords called off an attack on the convent and made it clear that Isabella was safe only for as long as she was loyal. Isabella—and her successor, Janet Hoppringle—continued their work for the English.

8 George Eliot

There were few things that got the attention of the Tudor monarchs faster than writing a book called Ten Reasons (to be a Catholic), which Jesuit priest Edmund Campion did in 1581. The Earl of Leicester sent George Eliot, a known con artist, after the priest. Eliot was desperate to avoid a sentence for murder when he agreed to spy on the priest, collect the needed evidence, and ultimately arrest him. Eliot ingratiated himself into an Oxfordshire parish to keep an eye on the rogue priest, finally fetching the local magistrate to oversee the arrests. Campion managed to hide until the owner of the house at which he was staying requested that he give a sermon in the middle of the night. He finished the sermon, but the members of the household had gathered to hear it and woke those who were looking for them. The priest was ultimately hanged, drawn, and quartered.

7 Bertrandon de la Broquiere

In 1432, Frenchman Bertrandon de la Broquiere embarked on a year-long espionage mission to Palestine for the Duke of Burgundy and was tasked with gathering any military information that would assist in mounting a Crusade against the Turks. Bertrandon wrote that the Turks were disciplined but lacking in arms, and in retrospect, it seems as though he erred on the side of optimism. He also wrote of the helpful nature of those who cared for him while he was sick and painted many of the people he met as selfless humanitarians in spite of their different religions. His story was an incredible one, filled with near misses, traveling in disguise, and even joining a Muslim caravan to Bursa. In the end, he optimistically reported back in favor of a victorious Crusade for the Christians, but no Crusade happened as a result of his intel.

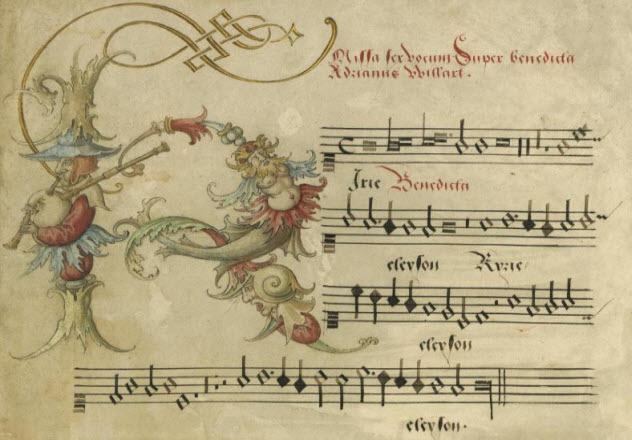

6 Petrus Alamire

Petrus Alamire is not his real name. The pun on musical notes (A-la-mi-re) was given to a spy working for Henry VIII—a spy who also made a career as a musician and scribe. Alamire was Bavarian, and his workshop produced some of the most beautifully illuminated manuscripts of the early 16th century. They were often gifted to members of the royal courts of Europe, who would then send for the mastermind who had created them. With unprecedented access to royal houses, Alamire collected intel that he passed on to other royals whom he wanted to keep indebted to him. Alamire supplied a massive amount of information to Henry VIII, his biggest client, on the movement of Richard de la Pole, the last Yorkist with any claim to the throne. But Alamire was also passing information to Pole and never returned to the English court after his betrayal was uncovered.

5 Francis Walsingham

Francis Walsingham, well traveled and fluent in Italian and French, was the spymaster for Elizabeth I for 22 years. Walsingham had more than 50 agents working in Turkey and other countries across Europe, but Elizabeth’s biggest threat was not far from home. Walsingham and his spies spent much of their careers gathering evidence of plots to overthrow Elizabeth and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. Even after the conspirators in the so-called Babington plot were hanged, drawn, and quartered, Elizabeth still refused to sign Mary’s death warrant. She finally signed on February 1, 1587. Walsingham oversaw Mary’s execution, the burning of her clothing, and the encasing of her body in lead (to ensure there would be no relics circulating). He also established a school for the spies under his control, where they were taught things like reading and writing coded messages.

4 Antony Standen

Antony Standen (aka “Pompeo Pellegrini”) was one of Francis Walsingham’s many spies. Based in Italy, Standen reported on the movements of the Spanish Armada, although he was living in exile because of his Catholic beliefs. Moving from England to Scotland to France and finally landing in Tuscany, Standen was fortunate enough to get friendly with Tuscany’s ambassador to Spain. In 1587, Standen was officially on Walsingham’s payroll and began passing him regular information that ultimately allowed Sir Francis Drake to move on the Spanish fleet while at Cadiz. Standen’s information helped to cripple the Spanish fleet. But by the time he finally returned to England in 1593, Walsingham was dead and Standen’s service was overlooked. Later, he attempted to help the Catholic Church regain a foothold in England and found himself in the Tower of London.

3 William Herle

In 1571, Philip II of Spain and Pope Pius V were in league with a Florentine banker named Roberto Ridolfi in an attempt to depose Elizabeth in favor of Mary. Ridolfi’s messenger, Charles Bailly, was arrested and sent to Marshalsea Prison. There, he met another prisoner, William Herle, who had been serving as a spy for Elizabeth I since around 1559. Herle had been arrested for piracy in 1570 (and 1567) and was planted in Marshalsea to extract information from Bailly. After Bailly was put in isolation, Herle stepped in as a questionable, shady character who could get certain things accomplished. Bailly began passing letters to his counterparts on the outside through Herle, who obligingly passed them along after he had copied them for his own employers. The unraveling of the plot changed the dynamic of the political spectrum in England and abroad.

2 William Stafford

To try to convince Elizabeth I to sign Mary’s death warrant, Francis Walsingham used all sorts of methods, including devising plots against Elizabeth’s life. William Stafford, the younger brother of England’s French ambassador, was completely Walsingham’s man. In 1587, Stafford came forward with a bizarre assassination plot that he had uncovered. France’s ambassador, Chateauneuf, and his secretary had reportedly recruited Stafford to plant gunpowder under the queen’s bed to kill her. Eventually, the French ambassador and his secretary were cleared of the accusations, and Walsingham concluded that Stafford had been using his position to extort money. Even so, Stafford remained in Walsingham’s service. It remained unclear if Walsingham was behind the whole setup or if Stafford had decided to give Elizabeth another reason to be wary of assassination attempts.

1 Madame de Sauve And The Flying Squadron

According to the memoirs of Pierre de Bourdeille, Catherine de’ Medici kept 86 (or 300) ladies-in-waiting to lure the men of the court into their beds to extract top secret information. Catherine then used the information from her “Flying Squadron” to secure her own position and that of her family. The most notorious of these women was Charlotte de Beaune, Madame de Sauve. Catherine’s daughter, Marguerite, wrote extensively about Charlotte’s wooing of both Marguerite’s husband and her brother. Marguerite claimed that her mother had pitted the two men against each other with a maneuvering temptress in the middle, but the truth of Catherine’s manipulations of the men and women in her court is rather cloudy. Read More: Twitter