Charles Lindbergh, the first aviator to cross the Atlantic alone, his wife, Anne, and his son, 20-month-old Charles Jr., had moved to a home in rural New Jersey to escape the press coverage that followed them everywhere. The power couple and their baby were like the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge today—everyone on both sides of the Atlantic knew and loved them. Everyone knew their baby as well. Yet before they had even finished moving in, the Lindberghs’ child was kidnapped, and a media circus like no other descended upon them. Two months later, it was discovered that the child had been mercilessly killed. The dastardly plot had been carried out by a nearly illiterate German immigrant who had come to the country illegally—a carpenter named Bruno Hauptmann. Though Hauptmann maintained his innocence, he was convicted and later executed in “Old Smokey,” New Jersey’s electric chair. Here are some little-known facts about the case.

10 Newspapers Published The Daily Diet Of Charles Jr.

Initially, it was thought—and hoped beyond hope—that this was a simple kidnap for ransom. If their child was still out there, the Lindberghs wanted him to be cared for properly. Charles Jr. had been recovering from a cold. This was actually the reason why Betty Gow accompanied the Lindberghs on their journey from Englewood, where they had been staying at Anne’s parents’ estate, to Highfields, their newly built mansion. As the baby’s nursemaid, Gow was needed to take care of the sick child. Though doctors advised that it wasn’t really necessary, Anne released a statement detailing her son’s daily diet, hoping that the kidnappers would feed him properly. It was broadcast over the radio and slathered over the front pages of regional newspapers: A half cup of orange juice on waking. One quart of milk during the day. Three tablespoons of cooking cereal morning and night. Two tablespoons of cooked vegetables once a day. The yolk of one egg daily. One baked potato or rice once a day. Two tablespoons of stewed fruit daily. A half cup of prune juice after the afternoon nap. Fourteen drops of viosterol, a vitamin preparation, during the day.

9 Mobsters Offered Their Assistance From Prison

Speculations ran wild as to who might have kidnapped the Lindbergh baby—and why. Who would be brazen enough to snatch such a famous child? Of course, suspicion immediately turned to the mob. Imprisoned mobsters were only too happy to offer theories on who had done it or information leading to the child. In exchange, they wanted certain favors or even release from prison. From his cell in Chicago, Al Capone graciously offered a $10,000 reward for information leading to the capture of the kidnapper. He also claimed that if he were released from prison, he and his henchmen would search for the perpetrators. A national debate ensued as to whether Capone should be released. Then Elmer Irey, the IRS agent who had placed Capone behind bars, put the kibosh on the speculation, noting that Capone would likely flee the country if he were set free. Mobster Abner “Longie” Zwillman also offered a reward for the return of the Lindbergh baby. He even met with members of the underworld who claimed to have information on the boy’s location. But it turned out that these figures were con men themselves. Zwillman later explained that this was simply a matter of business. The kidnapping occurred during Prohibition, and with heightened police scrutiny, Zwillman was worried that his alcohol-carrying trucks would be stopped and searched.

8 Charles Lindbergh Was Involved In The Investigation

Charles Lindbergh, a powerful man and strong leader, directed a significant amount of the investigation himself. In fact, Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, the superintendent of the New Jersey State Police, was accused of bungling the investigation because of Lindbergh’s interference. For his part, Schwarzkopf admitted that he viewed Lindbergh as a friend: “I admit there wasn’t one single, important step taken by us . . . until we consulted Colonel Lindbergh to learn if we would be interfering with his chances of getting back the baby.” However, even Schwarzkopf was frustrated with the level of intimacy between Lindbergh and his attorney and personal friend, Colonel Henry Breckenridge. Lindbergh listened to Breckenridge—and not the police—for advice on what to do. It got to the point where Schwarzkopf was considering charges of conspiracy. After Dr. John Condon was appointed as the go-between for the Lindberghs, Charles accompanied Condon on a trip to speak with the kidnapper. On April 2, 1932, Lindbergh drove himself and Condon to a local cemetery to speak with the kidnapper and arrange for delivery of the ransom. Though Lindbergh stayed in the car—the kidnapper would only speak with Condon—he testified at trial that it was Hauptmann’s voice he heard in the cemetery. Once the child’s body was found, both Lindbergh and Breckenridge backed off. Schwarzkopf reflected sadly, “Of course, when the child was found, we knew we had waited [for instruction from Lindbergh] vainly.” The remainder of the investigation was carried out by the appropriate authorities.

7 The Body Was Found By A Truck Driver

The discovery of the child’s corpse was made by William Allen, an assistant on a delivery truck with fellow employee Orville Wilson. On May 12, 1932, they were carrying tinder. About 6 kilometers (4 mi) from the Lindbergh estate, Allen pulled to the side of the road to relieve himself in the woods. As he walked into a grove of trees, Allen was shocked to see the half-buried corpse of a small child through the underbrush. He rushed out of the woods and shouted to his coworker, “Don’t know about anybody losing a child except Colonel Lindbergh. Let’s get out of here!” The two drove to Hopewell to find a police officer, and after completing their delivery, they guided him to the corpse of the infant. As an article in Time magazine put it, “If a Negro from Marshall’s Corner, NJ, had not decided to get out of his truck and relieve himself in the woods . . . a half-dozen accredited negotiators and a hemisphere’s police would still be looking for kidnapped, murdered Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr.”

6 The Defense Immediately Moved To Dismiss The Case

A trial begins with the prosecution giving their opening arguments—a monologue by a prosecuting attorney that lays out their explanation of how the crime took place and what they plan to prove. The prosecution then calls and questions their witnesses. In an act of showmanship worthy of the biggest celebrity trial of the century, defense attorney Edward Reilly called for a mistrial immediately after the prosecution’s opening arguments: “If Your Honor please, I move now for a mistrial on the impassioned appeal of the attorney general, not being a proper opening, but merely a summation and a desire to inflame the minds of this jury against this defendant before the trial starts.” He further moved for the dismissal of a juror. Both motions were denied, and Reilly asked for an exception, formally stating that he disagreed with the ruling of the court. The exception was granted.

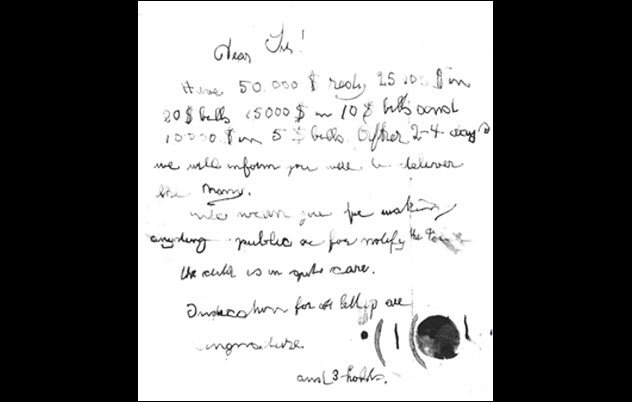

5 The Forensic Evidence

The trial of Bruno Hauptmann in the Lindbergh baby kidnapping was one of the first cases based on forensic evidence, and that evidence still holds up today. The prosecutors used fingerprint specialists, handwriting experts, and a xylotomist (a wood structure specialist). The most damning evidence against Hauptmann was the wood grain evidence provided by Arthur Koehler, a member of the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Koehler actually contacted the police to offer his services, as the state police had never heard of a “wood expert.” He testified that toolmarks on the ladder matched tools found in Hauptmann’s possession and that the wood grain on a rail of the ladder matched wood cut from Hauptmann’s attic. Handwriting experts testified that Hauptmann’s handwriting matched that of the ransom notes and that he consistently misspelled certain words. In 2005, the truTV show Forensic Files reexamined evidence from the Lindbergh case. Both of their forensic document examiners concluded that Hauptmann had written the ransom notes, and their wood grain expert found that the rail from the kidnapper’s ladder had come from Hauptmann’s attic.

4 The Raucous Crowds Outside The Courthouse

The trial took place in Flemington, a small town in central New Jersey. In the 1930 census, Flemington had about 2,700 residents. So imagine the chaos when 700 reporters, cameramen, and videographers descended on the town. There were also 5,000 spectators—nearly double the population of the town. They surrounded the 100-year-old courthouse, which could only seat 500 people. During the testimony of the Lindberghs’ nursemaid, the prosecution halted their questioning and asked the judge to send police officers outside to quiet the crowds. The 1930s had their problems with the press, too. Upon the opening of court one day, the judge lectured the spectators. Apparently, someone had sneaked a camera into the courtroom. The judge warned that if it was done again and he found out who was responsible, he would “take such measures as the court deems expedient in the matter.”

3 Identification Of The Body

When the body of the Lindbergh baby was found, it was in bad shape. The body had been in the woods, partially buried and decomposing for two months. The man who found it described it as a “skeleton.” What hadn’t decomposed had been partially eaten by animals. The boy’s body was identified by his father and Betty Gow, his nursemaid. The primary identification was of the baby’s nightshirt, which Gow had hastily stitched together from a bit of cloth given to her by the Lindberghs’ maid, Elsie Whately. Both Gow and Whately testified to this in court and identified the cloth and thread used in the garment. The other forms of identification were the child’s teeth, hair, and overlapping toes. After identification, the boy’s body was cremated almost immediately on the insistence of his father. No further forensic testing, including DNA testing, was ever possible.

2 Bruno Richard Hauptmann Had A Criminal Record

Though his attorneys and his wife, Anna, would try to paint him as a model citizen, Bruno Hauptmann was no stranger to a life of crime. Upon his return to Germany after World War I, Hauptmann and a friend burglarized three homes and even used a gun to rob two women pushing baby carriages. It was also rumored that Hauptmann had burgled the home of the mayor of Kamenz, his hometown, using a ladder to gain access to the second story, which is the same method of entry used in the Lindbergh kidnapping. Hauptmann was convicted of the burglary and served four years of a five-year prison sentence. Shortly after his release, Hauptmann went back to his old tricks. He was arrested for stealing some strips of leather. As he was awaiting trial, he escaped from prison, leaving his prison clothes neatly folded in his cell with a note that read: “Best wishes to the police.”

1 Anna Hauptmann’s Campaign For Bruno’s Innocence

For the rest of her life, Anna Hauptmann tirelessly campaigned to have the 1935 conviction of her husband, Bruno, overturned. She always maintained that her husband was with her on the night of the kidnapping. As recently as 1981, she filed a wrongful death suit against the state of New Jersey, alleging that witnesses lied and police covered up evidence that proved the innocence of her husband. She also wanted $100 million in damages. Despite her repeated attempts to take legal action, the courts ruled against her every time. The state legislature and Governor James Florio also ignored her pleas. Anna Hauptmann died in 1994 at age 95. She had never remarried or removed her wedding band. Her steadfast resolve convinced some people that she was right. Her pastor explained, “Our congregation loved her, her indomitable spirit, and her belief in her husband’s innocence. She convinced all of us he was innocent.” In 1992, Anna said, “God knows who kidnapped that baby. God knows all things. If I die before Richard’s name is cleared, I know He will do it in His time.” Hannah Taylor is 27 years old and hails from Flemington, New Jersey. You can follow her freelance research into the Lindbergh case and other intriguing tales at morbidstreak.blogspot.com.