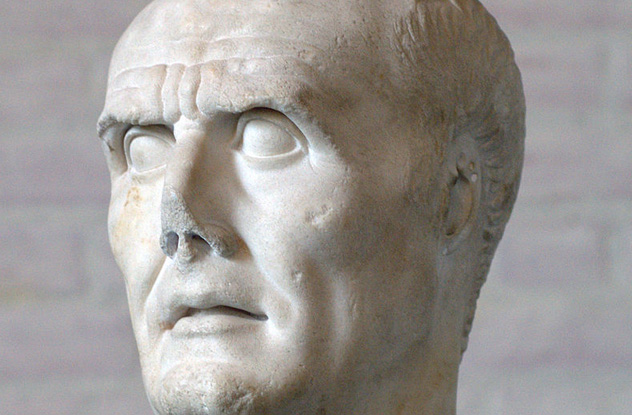

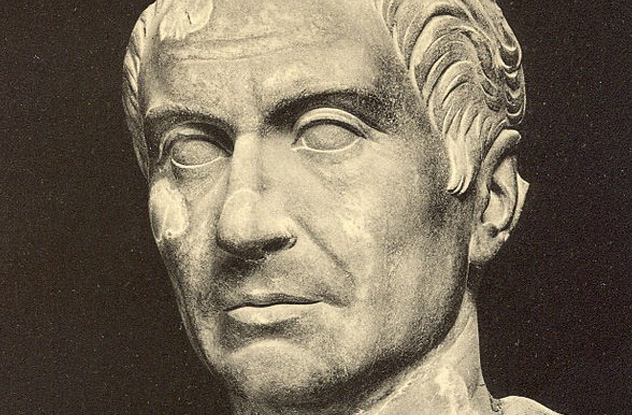

10Marius

Gaius Marius is almost forgotten today, but he arguably did more than anyone to ensure the overthrow of the Republic. He was one of ancient Rome’s greatest generals, famous for his victory over nomadic German tribes that threatened Italy. But to defeat the Germans, Marius had to change Roman society forever. Rome’s legionaries were traditionally small landowners, who served for a short term before returning to their farms. However, Rome’s overseas conquests required legionaries to be away from their farms for long periods, plunging many into poverty. Wealthy aristocrats bought up small estates and merged them into huge plantations. This meant that Rome struggled to find enough soldiers. Marius’s solution was to allow the urban unemployed to join up. This turned the legions into a full-time profession, with paid solders serving for up to 25 years. The manpower allowed Marius to defeat the Germans, but it also created a dangerous new political force.

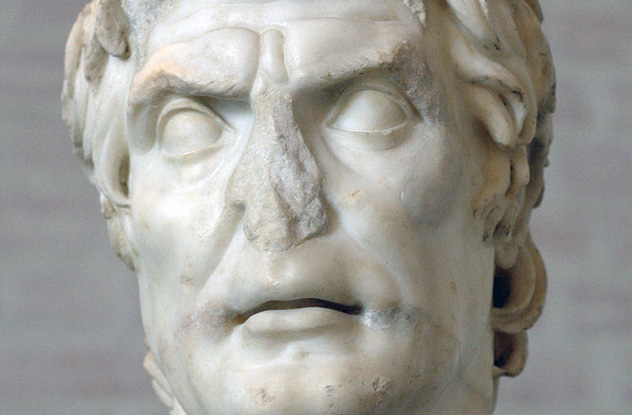

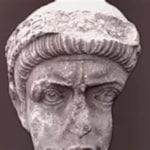

9Sulla

Marius may not have realized the implications of his reforms, but one of his subordinates did. Lucius Cornelius Sulla distinguished himself under Marius and then took overall command against an Italian revolt. In 88 BC, he was chosen to lead the war against Mithridates of Pontus. However, Marius jealously had the command transferred to himself. The war against Mithridates promised to be extremely lucrative, and Sulla’s legions weren’t willing to miss out. A civil war broke out, which ended when Sulla’s professional soldiers took Rome after bloody fighting. Sulla was declared dictator, and the River Tiber ran red with the blood of his enemies. In 79 BC, he announced he was satisfied with his reforms and retired, restoring democracy to Rome. It didn’t matter—-it was now clear that the legions were more loyal to their generals than Rome. The path to dictatorship had been established. The only question was who would take it next.

8Lucius Licinius Lucullus

In fact, while Sulla was still dictator, a threatening youth appeared at the gates of Rome. His name was Gnaeus Pompeius, but he was extraordinarily vain and relished the title of Pompey the Great. After inheriting an army from his father, he had defeated Marius’s loyalists in Sicily. Now, he demanded Rome celebrate him with a triumph. Sulla refused, but Pompey informed the aging dictator that “more people worship the rising than setting sun” and declined to disband his legions. Unnerved, Sulla gave in and allowed the triumph. Later, an aristocrat called Lucullus was chosen to lead a war against Mithridates. He was a good general, but too arrogant to recognize the new reality and bribe his troops with plunder. Soon, an officer named Clodius began stirring discontent, pointing out that Pompey richly rewarded his soldiers, while Lucullus gave his nothing. Before long, the legions mutinied and Lucullus had to be replaced with Pompey.

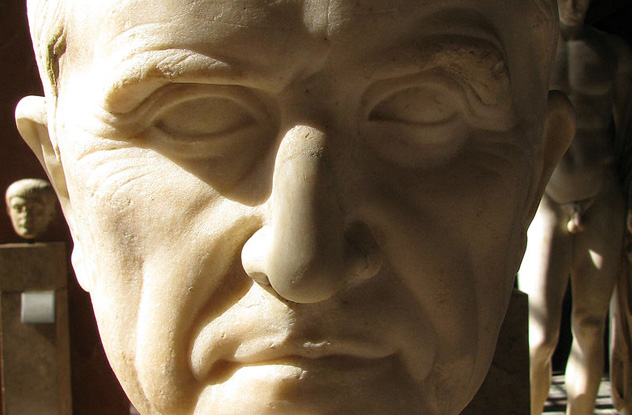

7Crassus

Pompey won great victories in the east, which were watched jealously by his rival Marcus Licinius Crassus. A key supporter of Sulla, Crassus helped execute the dictator’s enemies, then snapped up their property for a nominal fee. Some wealthy landowners were marked for death simply because Crassus wanted their land. With the profits, he got into moneylending and tax-farming. Before long, he was the richest man in Roman history. But Crassus still lacked military glory and respect. Although he had ensured Sulla’s victory outside Rome, Pompey had stolen his thunder. Then, Crassus defeated Spartacus’s slave uprising, only to discover that Pompey had arrived at the last minute, massacred some stragglers, and taken credit for putting down the whole revolt. Unsurprisingly, the two men became deadly enemies and conflict between them seemed inevitable. As Pompey prepared to return from the east, all Rome trembled.

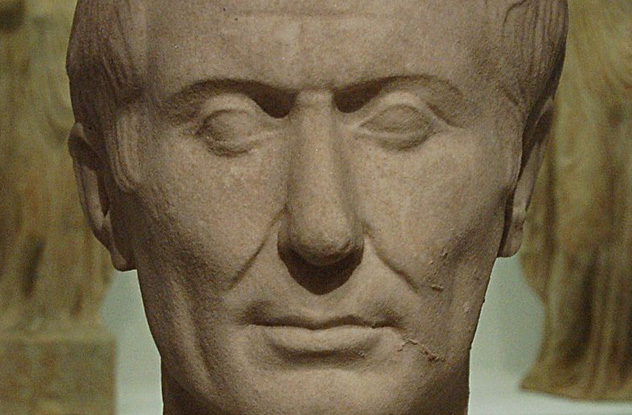

6Julius Caesar

But everyone reckoned without a rising politician named Julius Caesar. Born to an ancient but impoverished noble family, Caesar had made a good name for himself and was elected to a string of offices. He was heavily in debt and had survived by becoming a close supporter of Crassus. But he was also on good terms with Pompey and remained popular with the people. Caesar realized that, while Crassus and Pompey hated each other, their goals weren’t actually mutually exclusive. Pompey wanted land for his veterans, while Crassus wanted a glamorous military command and legislation that would help his business interests. Arranging a meeting, Caesar pointed out that Crassus and Pompey risked destroying themselves in a clash. But by working together, Rome’s richest man and its greatest general would be unstoppable. The three men agreed to form an alliance, with Caesar as the political frontman in the senate. Together the three men would be known as the First Triumvirate.

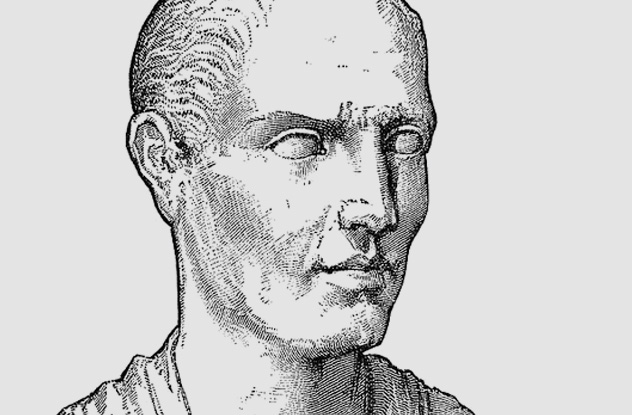

5Cato

By this time, Rome was a sea of corruption, with bribery and intimidation commonplace. But one man stood above it all. Marcus Porcius Cato was a man of iron integrity who openly held his fellow Romans in contempt. This won him the admiration of the Romans, who agreed that they were a pretty contemptible bunch. However, Cato’s refusal to compromise his beliefs would have disastrous consequences. It was Cato who prevented Pompey from giving his veterans land grants. Pompey then offered to marry Cato’s niece, but received a furious response: “Cato is not to be captured by way of the women’s apartments.” The arrogant general felt humiliated and couldn’t understand why the Romans supported Cato over him. Caesar and Crassus also tried to reach out to Cato, but the senator wouldn’t consider any deal with those he considered immoral. This relentless opposition was a key reason why the three men felt the need to form the Triumvirate.

4Clodius

Although the Triumvirate dominated Rome, senators like Cato and the famed orator Cicero continued to resist. However, the Triumvirate soon got its way: Pompey’s veterans got land, Crassus took command of a glamorous war against the Parthians, and Caesar received his own war on Gaul. Meanwhile, a dangerous new force arrived on the political scene. Clodius, the officer who incited mutiny against Lucullus, had returned to Rome, where he continued his rabble-rousing antics. He sensationally gave up his aristocratic status and declared himself a plebeian. He began to whip up the Roman poor into armed mobs, who rampaged through the streets attacking his enemies. The Triumvirate soon formed an alliance with Clodius to get rid of their enemies. First, he used his position as Tribune of the Plebs to get Cato sent to govern Cyprus. Then, he sent his gang after Cicero. With his life under threat, the senator fled Rome as Clodius’s mob burned his house down and built a temple to liberty from the rubble.

3Milo

Clodius was triumphant and ensured his popularity among the lower classes by securing free wheat for the poor (Rome’s version of welfare). Meanwhile, with Cato and Cicero gone, the Triumvirate began to splinter. Crassus’s old dislike of Pompey (pictured) emerged and he encouraged Clodius to turn on the general. To his horror, Pompey found himself jeered in the street. In the forum, one of Clodius’s gangsters pointedly dropped a dagger while walking toward the general. Pompey was forced to beat a hasty retreat, with Clodius’s laughter ringing in his ears. But Pompey the Great was no pushover. He had a supporter named Milo elected tribune and brought in gladiators and hired toughs to back him up. Milo’s professional fighters clashed with Clodius’s larger gangs and soon the whole city was a war zone. Things came to a head when Milo and Clodius accidentally ran into each other on the road and one of Milo’s gladiators killed Clodius with a javelin. Mad with grief, the mob placed Clodius’s body in the senate and burned the building down on top of him.

2Gaius Claudius Marcellus

In panic, the senate turned to Pompey, who put down the remains of Clodius’s gangs and restored order. Then, word arrived that Crassus had been killed fighting the Parthians. Things were looking up for Pompey, but there was a complication. Caesar had been unexpectedly successful in the north, conquering all of Gaul. Suddenly, Caesar was a real rival to Pompey, enormously wealthy from his conquests and commanding the loyalty of a battle-hardened army. As the senate became increasingly nervous of Caesar’s power, they turned to Pompey as the one man who could stop him. The issue came to a head in 50 BC, when the consul Gaius Marcellus recklessly ordered Caesar to give up his command and return to Rome. Without the protection of his army, Caesar was sure his enemies would have him prosecuted for exceeding his authority. In January 49 BC, he took his legions across the Rubicon river and marched on Rome.

1Pompey The Great

As insurance against Caesar, Marcellus had appointed Pompey commander of the legions in Italy. But Pompey realized that his green recruits were no match for Caesar’s veterans and decided to abandon Italy. This was a pragmatic move, but it handed the initiative to Caesar. In fact, Pompey’s whole campaign was dogged by a curious timidity. Pompey was still a great general, and he consistently outmaneuvered Caesar, but he also seemed intimidated by the younger man’s bold moves. First, he lured Caesar into modern Albania, but he failed to attack before Caesar’s reinforcements arrived. An attempt to starve the enemy into submission failed. Finally, he defeated Caesar at Dyrrhachium but failed to press the advantage. Finally, Caesar’s innovative tactics won a crushing victory at Pharsalus. Pompey fled to Egypt, where the Pharaoh had him murdered. Although Caesar himself would later be murdered by his opponents, it didn’t matter. The Republic was dead, and his heir Octavian would become the Emperor Augustus.