From nearly achieving impossible-sounding speeds to self-harming and even a bit of banditry, these celestial objects are a lot more versatile than we give them credit for.

10 Spin Really, Really Fast

For the first time, scientists accurately measured a supermassive black hole’s spin. And it’s a doozy: 84 percent of the speed of light. NGC 1365’s central black hole, 60 million light-years away, is mind-numbingly fast as well as enormous. It’s 3.2 million kilometers (2 million mi) across and boasts several million solar masses. As it spins, it drags space-time along with it, creating a scorching maelstrom of X-ray-spewing gas and dust that spirals down its drain. The matter likely fell from a single direction, giving it the constant unidirectional push required to attain such speeds.[1]

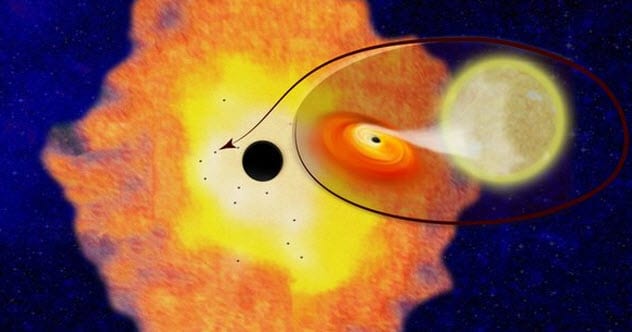

9 Prowl In Packs

The largest galaxies seen today are seeded by supermassive black holes so immense that they can’t be the product of a single star. So, scientists think “density cusps”—such as star clusters, groups of dying binary stars, or numerous smaller black holes—smash together to birth the mysterious supermassives. Now there’s direct evidence for that. X-ray analysis reveals that the Milky Way’s center hides a density cusp, a “village” of 12 potential black holes circling the periphery of our central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*. It suggests that as many as 20,000 additional black holes could be swirling around the galactic center.[2]

8 Chuck Jupiter-Sized ‘Spitballs’ (Sometimes In Our Direction)

According to theory and simulations, a star strays too close to the dormant Sagittarius A* and gets pulled into spaghetti strands every 10,000 years. The monster devours half the material and flings the other half into space. But some of the infalling material remains at such a distance that it can fuse into planet-sized fragments. The scary part? These fragments, which can be as large as Neptune and or even larger than Jupiter, are thrown into galactic space at speeds of 3.2–32.2 million kilometers per hour (2–20 million mph). It is believed that these “tidal disruption events” will eject 100 million such bodies, possibly at us, during the Milky Way’s life.[3]

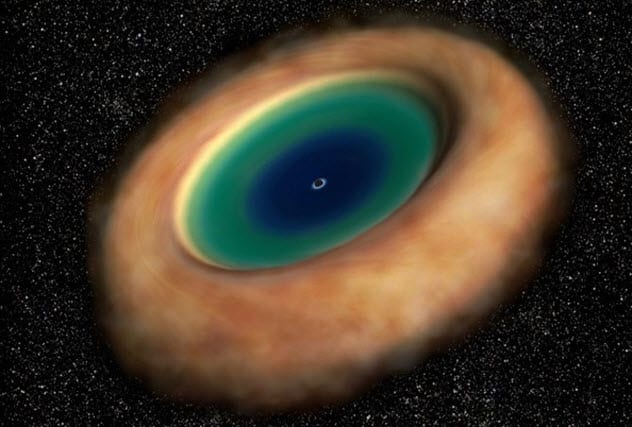

7 Reveal The Galactic Past

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has provided the first image of a black hole’s torus, the gassy, dusty doughnut of debris whirling around its black maw. The landmark torus resides 47 million light-years away in the constellation Cetus. And at a mere 20ish light-years across, it demonstrates ALMA’s acute sensitivity. From the torus, astronomers can read the galaxy’s past, deducing from its asymmetry and motion that it long ago merged with another galaxy.[4]

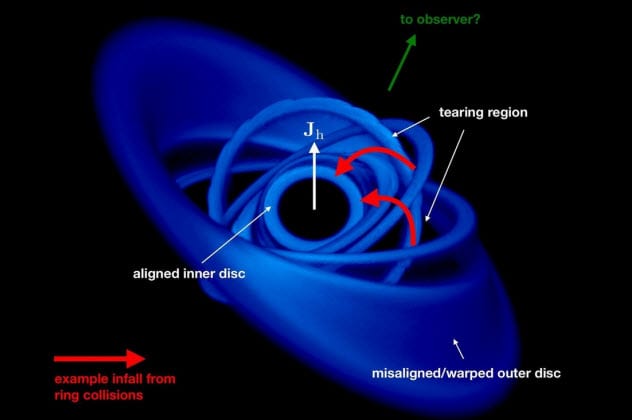

6 Propel Matter At Mind-Boggling Speeds

At a billion light-years away, galaxy PG211+143 is a sweet astronomical target because it’s ultrabright thanks to a feeding black hole at its center. Researchers observed an Earth-sized clump of debris as it fell toward the black hole and clocked it at 30 percent of the speed of light. Much faster than anything yet observed. Many bodies in space are aligned with one another, like planets orbiting in the same direction, but that’s apparently not true of matter falling into a black hole. These rings of matter are disordered. They crash into each other, negating rotational velocity and consequently achieving speeds of 100,000 kilometers per second (62,000 mps).[5]

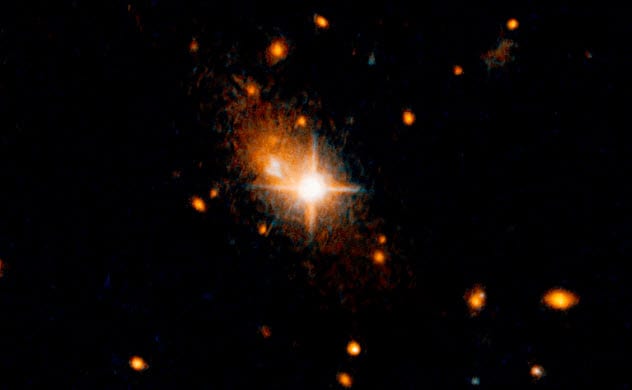

5 Exile Themselves

Astronomers theorize that black holes are sometimes ejected from their galaxies, and the strongest evidence yet comes from eight billion light-years away. The quasar is named 3C 186, and it’s an astounding one billion solar masses. Surprisingly, it’s making a speedy exit from its host galaxy cluster. Researchers measured its gas cloud zooming away at 7.6 million kilometers per hour (4.7 million mph). That means it could travel from Earth to the Moon in three minutes. Gravitational waves, the product of two gigantic black holes merging, are responsible. They shoved the resultant mega-gigantic black hole from its spot with the power of 100 million simultaneously exploding supernovae.[6]

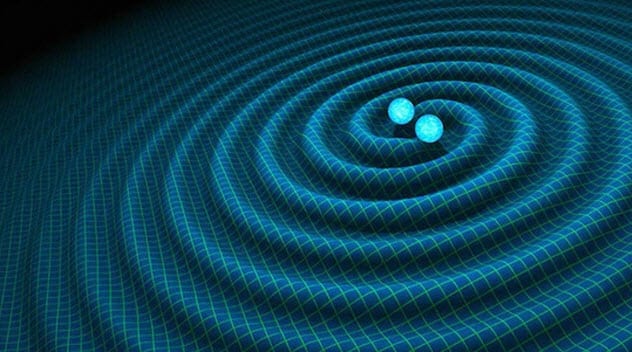

4 Steal From Bigger Black Holes

Astronomers have confirmed five instances of merging black holes producing gravitational waves, but a certain two black holes were apparently too massive. Instead of the expected 10–15 solar masses, researchers measured them at around 20 solar masses each. And it’s because they’re stealing food from the much larger, meaner black hole at the galaxy’s center.[7] The thieves were sizable stars that collapsed into black holes and wandered toward the chaotic galactic center where gas and dust funneled into the central supermassive black hole. They pilfered the material and grew nearly three times as massive before merging.

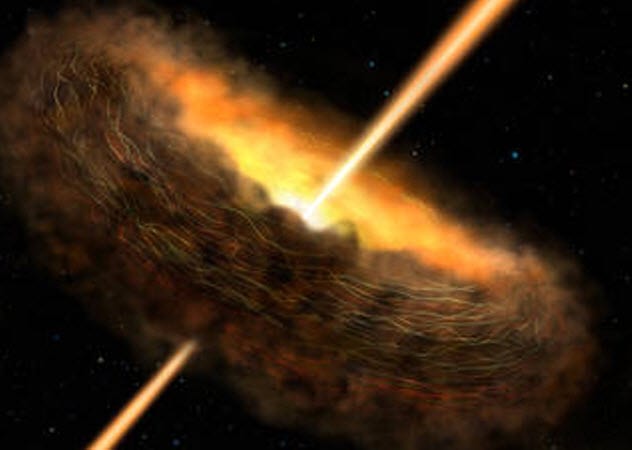

3 Use Magnetic Fields To Feast

One major factor dictating a black hole’s mass could be a magnetic field. Scientists studied the closest active galaxy, the 600-million-light-year-distant Cygnus A, and found a strong magnetic field around its energetic, “radio-loud” nucleus. Cygnus A’s black hole is active, blasting out collimated jets of radiation from its poles. And it’s getting help from the magnetic field surrounding it. The field traps material in a ring, or torus, around the black hole, pushing the debris into its gaping mouth. Researchers say that the difference between active galaxies like Cygnus A, and inactive ones like ours, could be the presence of such a magnetic field.[8]

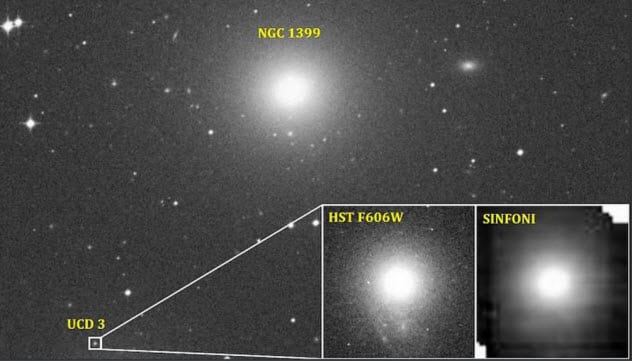

2 Hide In Tiny Galaxies

Fornax UCD3 has just 100 million stars compared to the several hundred billion in our galaxy, and they all occupy just 300 light-years of space-time. So even though UCD3 is puny, it’s among the densest galaxies, belonging to a family of “ultracompact dwarfs.” At its heart lurks a supermassive, 3.5-million-solar-mass black hole. It’s almost as hefty as the Milky Way’s Sagittarius A*, though our galaxy is 150,000 light-years across. It’s the fourth supermassive black hole discovered within an ultracompact dwarf. It constitutes 4 percent of the total galactic mass, though normal values are about 0.3 percent. It’s likely that UCD3 was once larger, but a close encounter with a more massive galaxy stripped its stars.[9]

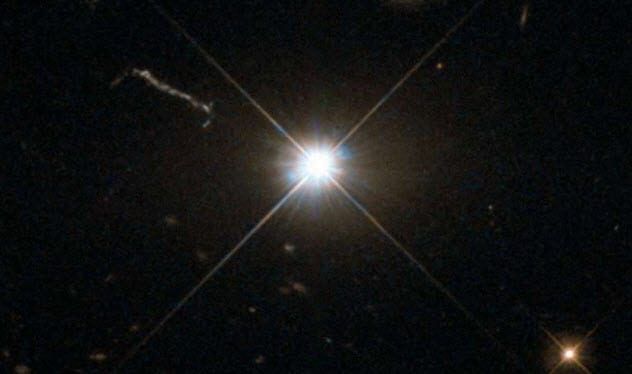

1 Erase Our Sun In Two Days

Astronomers have found a mind-bendingly (and mysteriously) voracious black hole in the relatively barren, calmer early universe of 12 billion years ago. It’s a quasar that consumes the equivalent of the Sun every two days. It burps and whips out so much ultraheated gas and dust that it shines a thousand times more brilliantly than its host galaxy. It’s unknown how it grew so fat during the “dark ages” of the universe, but what is known is its raw power.[10] If transplanted to the center of the Milky Way (25,000 light-years away from us), it would obscure the stars, shine 10 times brighter than a full Moon, and likely kill us with X-rays.