But many of us don’t know that medieval towns were havens for runaway serfs, a place where they could become free by law if they laid low long enough. Or that medieval people frequently ate fast food—probably even more so than we do now. Today, we’re bringing you 10 misconceptions about medieval town life.

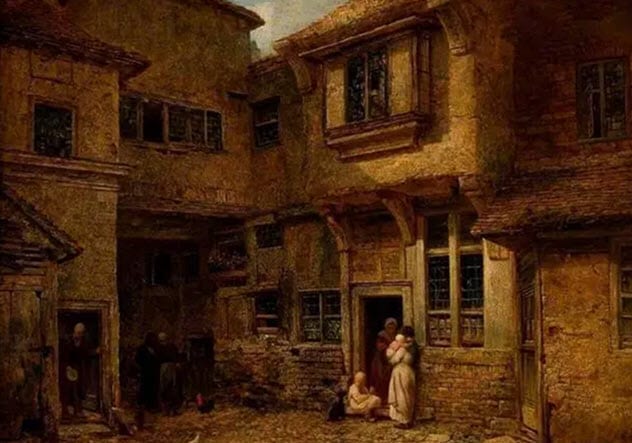

10 Rich Innkeepers

We all think the stereotypical medieval innkeeper was a big, burly man with a dirty apron who was wiping a mug with a stained rag. He was rugged, tough, and not opposed to throwing out a patron if they caused trouble. He was not wealthy—and he certainly was not a nobleman. This might have applied to the people who ran the informal alehouses. But the medieval innkeeper was often a man or woman (10–20 percent of them were women) of wealth and taste. This is because the average medieval traveler was a wealthy man—a government official or merchant or maybe a prestigious member of the clergy. These kinds of people needed a stable for their horses and nice, clean beds. Best of all, they usually came with a fair amount of cash. Due to the caliber of their usual clientele, inns were often hubs of trade and gossip. Many innkeepers ran small businesses on the side and traded valuable commodities. They knew their stuff because they frequently met traders of all kinds.[1] With their position at the center of society, these innkeepers were individuals of repute and often knew most people in their towns. As such, many innkeepers were also landowners or elected officials, making them considerably powerful people!

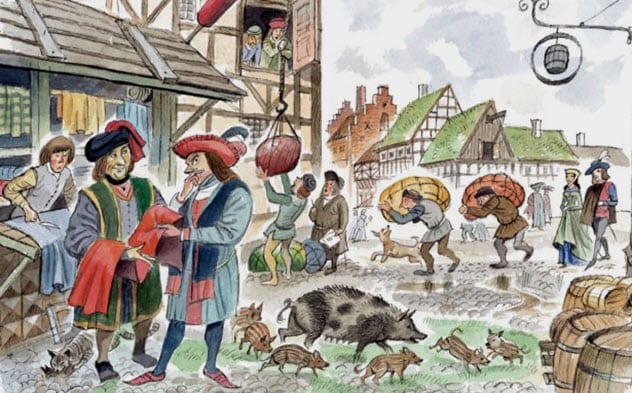

9 Fast-Food Meals

When we think of medieval cuisine, we don’t think of fast food. But for many medieval townies, this was the only option. Kitchens required more room in medieval times as ovens were a lot bigger and a fire risk. Therefore, most people back then opted not to have one. In medieval Colchester, for instance, only 3 percent of households had a kitchen. It was much more common for people to take their unbaked food down to the local bakery where they would pay the baker a small fee for the privilege of using their oven. Even more frequently, medieval people headed to their local pie shops or bakeries and bought ready-cooked food to eat on the move. In fact, some employers offered their workers time and an allowance to buy lunch in the middle of the day. These fast-food shops often had their own quarters within town and frequently stayed open after dark. So even those laborers who worked all day could grab a bite on the way home. Pies, hotcakes, wafers, and pancakes were particular favorites, but meat pies were sold most frequently at these establishments. Until the modern era, pies were smaller and deeper. The pastry was much thicker and not intended for consumption. Instead, the pastry was more like a container for the food inside, which the hungry worker would scoop out and eat with his hands or his knife. This made meat pies a high-energy and very portable food.[2]

8 Vibrant Food

We often assume that medieval food was bland and boring. While it’s true that rural peasants in villages mainly ate homegrown vegetables and porridge, even this was made more interesting by adding some herbs from the vegetable garden. In towns, food could be just as exciting and interesting as it is today—if you had the money. The best place to find the flavors we’re used to now would have been London where the merchant ships from the continent would dock first. The farther you were from London, the more expensive the spices. In the town markets, you could find modern-day staples like ginger, pepper, cumin, and cloves as well as spices like cubeb that have fallen out of use in the Western world today. Judging by some of the recipes from the time, it was not uncommon to find things like rice in the town market that was imported all the way from Asia.[3] If you were rich enough to own a townhouse with its own cooking facilities, you almost always had enough money to afford the spices needed to keep your food interesting. And if you were a traveler stopping by a well-to-do inn or a high-end pie shop, you can be sure that they were also stocking up on spices to make their food more desirable than that of their competitors. On the other hand, if you were a lowly craftsman or apprentice, it’s likely that your main meal of the day was a bit of bread and maybe a cake or doughnut sweetened with honey but not with pricey sugar.

7 Old-Fashioned Sport

When we think of medieval sports, we think of things like archery and jousting. There is considerable evidence, however, that one of the most popular sports enjoyed by medieval people was a form of football which they called “ball.” The game was similar to modern-day soccer but with some key differences: The ball could be propelled with any part of the body (including the hands), teams were usually made up of 300–500 people, and fighting, kicking, punching, and generally playing people off the ball were normal. The game was popular and well-organized even at the start of the medieval period. When William FitzStephenin visited London in 1170, he remarked that the city’s youths loved to go out after dinner and play ball. He even noted that each trade had its own team. The game of ball was usually played between large teams of opposing professions—for example, the thatchers against the carpenters. But it seems that social differences could also be the basis for football teams. For instance, in the women’s-only version of the sport, it was common to see the married women line up against the unmarried women. Football was popular in medieval towns. Although the players usually retreated to the fields to play their games, they sometimes took to the streets, which often resulted in damage to property and widespread chaos.[4] In 1314, King Edward II tried to ban the sport in London. He encouraged people to take up the more respectable sport of archery instead. Ball continued despite the ban and survived further prohibitions during the reigns of Edward III and Edward IV to become the modern sport of soccer.

6 Town Curfews

Crime was a major problem in medieval times. No doubt it was fueled by the lack of a police force and the legal requirement for everyone to own a weapon. But medieval people did make an effort to crack down on crime, especially ones committed at night (when it was harder to find a witness) by issuing curfews in towns. Yes, if you spent the night in a medieval town, you were expected to stay inside after the ringing of the curfew bell, which usually happened just before sundown. If you ran an inn or alehouse, you were legally responsible for the actions of anyone who remained on your premises after the bell rang. So the proprietors of the rowdier establishments simply shoved their patrons out onto the street after curfew to be rounded up by the night wardens, who were usually just volunteers. The town gates were closed, and no one was allowed to enter or leave until morning. It wasn’t strictly illegal to be wandering the streets at night. If you were a laborer who frequently worked late or a person of good standing around town, you were likely to be ignored by the wardens, especially the ones who knew you or saw you every day. But average people could expect to be stopped and questioned by the warden about what they were doing or where they were going. If they didn’t have good answers, they would be escorted home or taken to the town jail, to be released when the bell rang again in the morning. It was a crime to travel without a lantern after dark or to be outdoors without a good reason.[5]

5 Gate Tolls

Much as tax is all but unavoidable today, it was the same in medieval times. We might not expect this considering the enormous amount of organization and effort required to run a proper system of tax. And while medieval taxes were much simpler than those of today, the tolls charged for entry into towns was precise and complicated in certain places. Gate tolls were one of the main sources of income for medieval town councils as they were lucrative and fairly simple to collect. For the most part, the right to leave and enter a town for free was extended to all residents. However, travelers had to pay a small fee to enter. Most tolls were collected from people traveling to market to sell their wares, and each town had their own lists of rates to charge for different types of goods. A list from medieval Tarascon has survived and was recently translated. This gives us insight into one medieval town and its attitude toward various kinds of goods. When we consider this alongside the fact that the gates were locked and barred each night, access to medieval towns looks much more regulated than we might expect. During periods of high unrest when Edward II reigned in the early 1300s, he routinely ordered the gates of London to be closed during the day, too. All those seeking to leave were thoroughly questioned about their motives by the gate guards.[6]

4 Legal Prostitution

We might begin to think that medieval towns, much like the lords in the countryside, were highly restrictive of the activities within their walls. But there were some freedoms allowed that even today are illegal or, at the very least, highly regulated. One of these areas was prostitution. Medieval society had very different views on gender, sex, and people’s behavior than we do now, and medieval individuals were altogether a lot more violent and used to hostile interactions. Thus, we see the widespread tolerance of brothels in medieval towns, even though sex outside of marriage was seen as sinful. Brothels were permitted for a rather simple reason. To the medieval mind, male lust needed to be sated in a safe way to protect the innocence of women. Prostitution was still monitored and regulated. In fact, brothels were required to keep detailed records of their operations that were freely accessible to council officials. Brothels also had to turn a profit to be viable. They certainly weren’t funded by the government or the church.[7] But in many places, the presence of a bawdy house wasn’t seen as a bad thing. It wasn’t entirely uncommon to see such institutions frequented or even owned by wealthy or high-ranking members of the clergy, even bishops. In some places, a brothel keeper had to be sworn in by the mayor of the town and would serve for a preset term. Afterward, a new one would be chosen. In some towns, such as medieval Vienna, only women were allowed to run a brothel. These measures were introduced to ensure the safety of both workers and patrons. Cheaper and sleazier establishments almost certainly existed in these towns, although they were unknown to the town councils.

3 Individual Freedoms

It is often believed that medieval people—especially the poor—lived highly restricted lives tied to the land on which they were born as the property of their lords. While this wasn’t the case everywhere—and peasants could take it to court if their legal master didn’t treat them right—this was broadly true for those who lived in rural areas. In towns, however, it was an entirely different story. Regardless of their level of wealth or past circumstances, anyone who lived in a town was considered a burgess of the town. They were freemen who owed obligation to no one. However, they still had to obey the law and pay their taxes. Even if the town was on the land of a local lord, who collected a percentage of the town’s profits in the form of tax, the residents themselves were obliged to the council rather than the local lord. (The council was elected by the residents.) When a town was granted a charter and became a borough, it (and its residents) became free of the lord’s influence.[8] Why would a lord do this? Because it earned him a profit. As places of freedom, boroughs were highly desirable places to live. A new town with a new charter could expect to see a boom in population as people moved there for the increased freedoms. This meant more land tax and trade toll income for the lord. A win-win situation! In many cases, even runaway serfs could become free if they were able to escape their lord’s clutches and settle in a town. If a former peasant lived solely within one town for a year and a day, he automatically became a burgess of the town and any previous obligations to his former lord were forgotten. Some towns even guaranteed their burgesses a portion of land, which they legally held for life and which couldn’t be taken from them. But this was less common.

2 Good Workmanship

In a time before human rights, quality assurance, and an organized police force, it’s easy to believe that shopping in the market would be much riskier than it is today. In some cases, that was true. Certainly, at the cheaper markets or the stalls of small, independent traders, the shopper had to keep his eye out for dodgy goods. Merchants often pulled tricks to deceive hasty customers—for example, covering a sack of bad grain with a small layer of fresh grain. There were laws against it, but they were often ineffective because dodgy trade was difficult to prove. When guilds developed, such practices became increasingly rare, largely due to the stringent standards to which guilds held their members. The main purpose of a guild was to ensure that people belonging to a particular trade could earn a decent living and had a form of social security in a time when governments didn’t provide welfare. At the height of the guilds’ influence, it was a legal requirement for someone practicing a particular trade to belong to that trade’s guild. A member of a guild could expect some form of health insurance and life insurance provided by the guild’s main fund as well as subsidies for poorer members or those with large families. Guilds also played a role in funding early public education, constructing churches, and helping members find apprenticeships or jobs for their children. In short, they were essential to many craftsmen in medieval times and provided much-needed security. In return, guild members were expected to produce goods to a particular standard. Nearly all guilds required their members to stamp their goods with the guild’s symbol. So if these products weren’t up to standard, customers could complain to the guild leaders.[9] Some higher-end guilds, like those for jewelers, even sent a high-ranking member to personally assess the quality of all jewelry made by members before it was sold. All prices were decided as a group, and undercutting other members was forbidden. There were also restrictions on competition. For example, advertising was banned as was buying a large stockpile of commodities or other goods to corner the market. However, craftsmen were allowed to put their individual wares on display in public so that potential customers could choose the best-quality goods on offer or support a favored trader. Of course, the effect of all this protectionism was that finished goods and commodities increased in price as the medieval period went on, which hurt the poorest people in society. But it meant that most goods found in the market were of a surprisingly high quality. At the very least, if you were disappointed with a purchase, you could complain to an official body and receive compensation.

1 Fluctuating Populations

Although most of us know that medieval towns were very small compared to modern ones, we may not know that town populations were much more flexible then than they are today. While an early town’s actual population might be fairly low, the number of daytime inhabitants could increase by as much as two or three times as traders and travelers made their way to that location to buy and sell or just pass through. There were several reasons for this. First, towns were loud, dirty, and relatively unsafe—the haunt of vagrants seeking protection from the law or just a dry alleyway to sleep while protected by the town walls. Second, living in towns was expensive and land was very costly. But the main reason: There was simply no benefit to living in a town for most people. In an age when the vast majority of people were engaged in rural professions or had rural skills, living in a town could actually be a hindrance. The only people who lived in towns were individuals engaged in crafts like blacksmithing or thatching (where there was continuous demand for their services), traders who needed to be close to their storehouses and the markets, and the wealthy. However, access to a town was very important. By 1300, nearly every person in medieval England lived within 10 kilometers (6 mi) of a market town. This made it easy for them to take a day trip to buy, say, a new shovel or plowshare or a chicken from the market if they’d had a good week and had some cash to spare. Then they could still make it home before dark.[10] On market days, it was customary for the town’s population to temporarily shoot up. This was especially true on fair days when people expected to find entertainment alongside the usual market goods. So, although only around 12 percent of medieval people actually lived in a town, the number of people who spent at least one day a week there was considerably higher.