But what about its history? How did we get here? How did heroin become the drug that everyone considers essentially the worst of the worst? This list seeks to break down the history of heroin into ten parts to form a narrative which tells the tale of its history, from its creation to the present day.

10 From Opium To Heroin

Heroin (also known as diamorphine) is synthesized from morphine, a potent opiate alkaloid which is derived from the poppy plant. Morphine is a highly addictive drug, and heroin was actually synthesized in an attempt to create a less addictive version of morphine. Heroin began to be sold at the end the 19th century. Heroin was widely believed to be less addictive than morphine and was distributed casually at local stores. Quickly, it began to take over, and people became addicted, with the most affected class being middle-aged women, particularly married women.[1]

9 The Invention Of Heroin

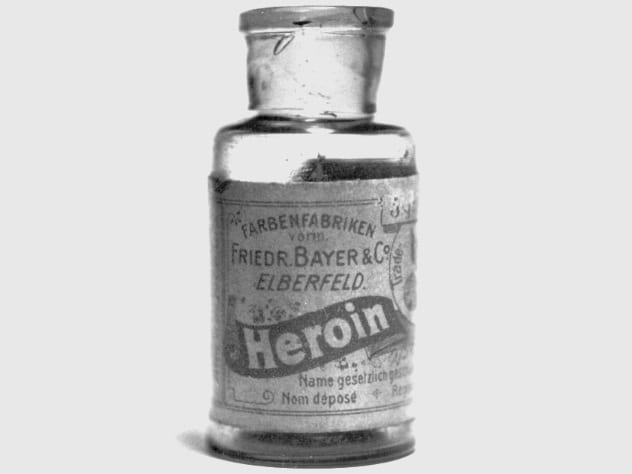

Heroin was first synthesized by a chemist named C.R. Alder Wright in 1874, and at first, nobody thought much of it. He was likely in search of additional compounds that could be derived from morphine, and his quest yielded no results. It wouldn’t be until 23 years later, in 1897, that it would be resynthesized by Felix Hoffman, who was working for the Bayer pharmaceutical company at the time. It all happened by accident. Hoffman was trying to synthesize codeine ( a slightly less addictive, less potent drug) from morphine but ended up synthesizing diamorphine instead—heroin. It was not weaker but rather somewhere in between 50 and 100 percent more powerful.[2] This was obviously going to be a big success, even if it came with some tragic addictive side effects. The quest to sell heroin to the public was just beginning.

8 Big Business

With heroin synthesized and its power realized, Bayer was anxious to sell this new, potent opioid to the public at large. But “diamorphine” didn’t sound all that appealing, so they looked to the traits they thought the drug would give its users and picked a particularly German name: Heroin. The name comes from the German word heroisch, which means “heroic” in English. (In fact, Bayer had already previously sold another drug under the name “Heroin.”) Users felt powerful, heroic, strong, and invincible, or so the name of the drug sought to convince them.[3] At the time, morphine was a highly addictive substance that society was attempting to get under control—heroin promised a way out of morphine addiction and was thus introduced as a safer alternative. It was put into everything from cough medicine to pain relievers and even marketed directly to children.

7 The Roaring Twenties

In was the 1920s. Jazz was popular, the stock market was on the rise, and the world was finding itself in a party-all-the-time state with little to no downtime. Europe and the United States had enjoyed a significant technological boost from the Industrial Revolution, and everything was going to work out fine. Booze was illegal in the United States, though still very obtainable, but along with the illegality of alcohol came a lot of heroin use. A lot. An article written by one William McAdoo and published on March 31, 1923, stated clearly that drug addiction, particularly opiates and heroin, was worse than alcohol during this time of Prohibition in the United States and can be quoted as saying: There is one thing that makes drug addiction much more serious than drunkenness from alcoholic liquors. The drunkard cannot conceal his vice.[4] There was a new kid on the block, and that new kid was heroin, a much less immediately detectable addiction that was already beginning to cause problems in its infancy. It wouldn’t be until 1924 that heroin was totally outlawed in the United States, driving its use completely underground to this day.

6 The 1930s

The 1930s rolled around, heroin was illegal in the United States, and governments around the world were starting to crack down, seeing the glaring societal threat that it posed. This, of course, left a vacuum in the market, and a lot of people were already hooked on the substance, meaning they’d do anything to get it and relieve themselves of the pain of withdrawal. In the United States, this opened the door for massive organized crime outfits, who were ready and willing to pick up the business that pharmaceutical companies and drugstores had been forced to abandon.[5] In the United States, the Mafia dominated the drug market, the vacancy which was left by the abrupt withdrawal of the pharmaceutical companies, and heroin’s popularity only continued to increase with its criminalization.

5 Drug Trafficking

The Mafia and other organized crime outfits assured that the drug trade between the United States and Europe was robust and perpetually flowing. Beyond the trade markets springing up in Europe and the United States that law enforcement simply couldn’t keep up with, the 1960s ushered in a new era of drug dealers, taking the trade to global proportions. Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and other Southeast Asian countries entered the game when the United States and France armed various groups in those countries in an effort to help them defeat Communist uprisings and maintain the status quo, giving them aircraft in the process.[6] This was ultimately doomed to fail, as interventionism usually is. In America, heroin was mainly used by social outcasts, adult criminals who had never belonged in society and had always been poor, while the housewives and suburban dads enjoyed their legal amphetamines and alcohol, respectively. This all changed with the Vietnam War, when American troops were sent to the front lines to fight off the perceived Communist threat in a conflict which wasn’t their own. The irony is that Southeast Asia is an area ripe for growing poppies, and with the new tools the Americans and French gave them, they took up the drug trade, supplying the American forces with heroin to calm their nerves, nerves which screamed like the gunfire from the hellish war they were in.

4 Vietnam

Vietnam was Hell—just ask anyone who went there, many of whom were sent by their government without their consent at frighteningly young ages. As the war dragged on, America started to see addiction in young people increase, as literal teenagers were sent to watch their friends die in a country on the other side of the world, only to return with deep and lasting scars. They turned to heroin, the trade of which was propped up in the US by organized crime, to soothe their pains and quiet their nightmares. Many servicemen were injured overseas and forced to self-medicate to relieve the pain of their injuries. As these mentally and physically scarred teens and 20-somethings came back from the war overseas, they reunited with friends, and heroin was no longer a drug for the criminal outcast but for anyone looking for a good time.[7]

3 The Superstar Drug

Since its resynthesis in the late 1800s, diamorphine was set to become a superstar drug, both literally and figuratively. It was potent, charming, and orgasmic (as described by users), and its danger added an element of risk to an otherwise seemingly boring and ordinary life. Its rise to prominence was only further fueled by the superstars who lived and died on it.[8] From Janis Joplin to Sid Vicious, heroin was the drug of rock stars, rebels, outcasts, and those who wanted to send a message to impressionable youth. In the United States, the Nixon Administration fought back with tough drug reforms and pushed the US Congress to pass a bill that appropriated $370 million to fight the river of drugs pouring in from Asia. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was established in 1973.

2 Public Policy

Heroin has been combated by two means, one of them seen as more effective than the other, and those means are education and justice. Questions about the legality of the drug have begun to be raised, and while it’s powerfully addictive, we’re left to wonder if criminalization is the correct solution. After all, the DEA was established in the 1970s, and we still have a massive problem with heroin today, so if the DEA’s job was to end heroin addiction by stopping the flow of heroin, one could say that it has largely failed. Few say that heroin should be totally legal, but many are starting to question our response to users and are calling for treatment programs in lieu of hard jail time, where users and addicts are likely to just find more heroin before being released back to the streets, where they can buy yet more heroin, of course.[9]

1 The Unexpected Surge

The modern opioid crisis, beginning around the turn of the 21st century and continuing to the present day, has shocked the Western world.[10] Unlike the heroin use of before, new, pharmaceutical-grade opioid drugs have been hitting the streets. Take fentanyl, for example. It is many times stronger than heroin, and the toll it has taken on society has been corresponding to its potency. Fentanyl deaths increased by more than 1,000 percent between 2011 and 2016, killing tens of thousands in the United States alone, according to the Centers for Disease Control. One thing is for sure, fentanyl makes heroin look like the good guy. So we’d expect that with the abuse of alternative and even legally prescribed opioids on the rise, heroin use must be going down, right? Wrong. Demographics which previously weren’t at risk for heroin use have now found their way to the streets to hit up the dealers, who are still out there on the corners in various neighborhoods worldwide. Many new heroin users got hooked on prescription opioids and then turned to the cheaper, comparatively less-of-a-hassle heroin when the medical community cut off their supply. We do not know what the future holds, but currently, there are teams of scientists all over working tirelessly to find a solution to the problem, such as nonaddictive opioid drugs. I think anyone who’s ever experienced an extreme injury would be inclined to say that we need these drugs, so it’s just a matter of finding out which drugs are the safest and which ones shouldn’t be employed at all. I like to write about the dark, the strange, and the unusual.