Many Christmastime traditions are often a tad unique and eccentric. Here, we take a closer look at some of the most surprising Christmas traditions and tales from around the world.

10 The Nikolaus Boot And Knecht Ruprecht

The Germans take their “naughty or nice list” stuff to a new level. On December 5, German children leave a boot outside their front doorways in preparation for Saint Nicholas Day. Sankt Nikolaus then checks his golden book for names of nice children. Good children will discover presents, candy, and chocolate inside their boots. Naughty kids who appear in the “black book” receive a bunch of twigs—and possibly a visit from Nik’s companion, Knecht Ruprecht. In other parts of Europe, like Austria and the Czech Republic, Knecht Ruprecht’s counterpart is more commonly known as Krampus. Krampus is a half-goat, half-demon creature that features an intimidating set of horns. During parade events, adults dress up as the hoofed creature and even bind themselves in chains. They then chase delinquent kiddies through the streets with bundles of birch branches. Krampus—in theory—drags captured children off to his lair before torturing or eating them. Krampus stems from Germanic paganism and Norse mythology. The fearsome creature is thought to be the son of Hel, goddess of the underworld.[1] A bizarre fusion of Christianity and the aforementioned traditions led to Krampus’s festive inclusion.

9 The Christmas Pickle

The Christmas pickle is perhaps one of the strangest things to adorn any American’s tinsel-laden tree. Typically, the glass pickle must be hidden among the tree’s branches. Excitable children are then tasked with hunting the camouflaged ornament on Christmas morning. Presents are awarded to the first super-sleuth who spots the pickle, and they receive good fortune in the future. The exact origins of this rare tradition are uncertain, but several theories persist. It was once thought that the pickle’s origins lied in Germany. However, the vast majority of Germans haven’t even heard of the quaint decoration. Another theory involves John C. Lower, an infantryman who enlisted during the US Civil War. The story goes that Private Lower was captured and taken to Camp Sumter, a Confederate POW camp. On Christmas Eve, a starving Lower begged one of the camp’s guards for a pickle. The guard is said to have obliged Lower’s request, a kindly act that supposedly saved the detainee’s life. Thus, a tradition was born. However, this story was refuted on the basis that the Civil War ended before the popularization of these glass ornaments. In fact, it is thought the Christmas pickle was the product of deft marketing—an attempt to promote and sell German-manufactured glass ornaments.[2]

8 El Gordo

Every December 22, Spanish residents eagerly await the Spanish Christmas Lottery. The top prize—El Gordo (aka “The Fat One”)—gets its name from its sheer size. In 2016, 70 percent of earnings from ticket sales were given back in prizes, with over €2 billion shared between lottery winners. In recent years, the top prize has been set at €4 million. The Spanish Christmas Lottery pays out more money, overall, than any other lottery draw. This is due to the large number of smaller cash prizes up for grabs. The high ticket prices mean the Spanish Christmas Lottery is a highly social affair. A single ticket sheet costs €200, while a tenth of a ticket (a decimo) costs €20. It’s not uncommon, then, for family, friends, and work colleagues to split the cost of a ticket sheet. Contrary to many other lottery systems, participants must buy preprinted tickets. As a result, they don’t get to pick their own numbers. During the draw, a group of Spanish schoolchildren fetch lottery balls from two golden drums—one containing the winning numbers, another containing the prize amounts. As they make their selections, the children sing the lottery results to an awaiting public. Due to the number of winners generated, it can take several hours to announce the results. Pupils are allocated to separate announcement “shifts” until all the balls are retrieved.[3]

7 Kentucky Fried Chicken

One’s mind does not instantly jump to Kentucky Fried Chicken when contemplating Christmas dinner. But for those Japanese citizens who celebrate the festive period, KFC is at the top of the menu. As a consequence of an extraordinary marketing strategy, KFC is now the feast of choice for many Japanese families over Christmas. KFC Japan (KFCJ) launched its wildly successful Kentucky for Christmas campaign during the 1970s. In doing so, it released products like the Party Barrel, touted as a substitute to more traditional Christmas meals. While only one percent of Japan’s population identifies as being Christian, Christmas is widely acknowledged and celebrated across the country. In Japan, December has become so busy for the fast food chain that many customers end up preordering their KFC special Christmas dinner. Those who do not preorder risk a lengthy wait in line. Millions of Japanese customers buy Kentucky Fried Chicken over the Christmas holidays, with the company’s ads featuring some of the biggest Japanese celebrities. It is thought that KFC Japan owes its popularity to the scarcity of turkey. A bunch of tourists had previously settled for KFC after struggling to find turkey. Upon learning of the group’s predicament, the manager of the country’s first KFC outlet, Takeshi Okawara, conjured up the Christmas-themed Party Barrel.[4] The campaign was an enormous hit and remains a template of modern marketing to this day. The Colonel’s Christmas buckets come complete with KFC, cake, and champagne. Just make sure you preorder over the holidays.

6 Night Of The Radishes

On December 23, residents of Oaxaca City celebrate the Night of the Radishes. Locals compete with one another to create the best radish-based displays, carving the vegetables into all manner of creative works. The tradition was a clever means of luring consumers to the local Christmas market. The event proved so popular that in 1897, the city’s mayor made the Night of the Radishes an officially recognized event. Separate land is now available for growing the festival’s radishes. The radish exhibitions go through adjudication each year, and the winner is awarded 12,000 pesos.[5] Mexican artists craft a variety of displays, carving radishes into nativity scenes, festive characters, animals, monsters, and popular folklore icons. The locals even display these elaborate works of art as Yuletide decorations around the home.

5 Candy Canes

The story behind the iconic candy cane remains shrouded in mystery. Still, we know straight candy canes were in circulation in Europe during the 17th century. Three theories pervade on how they earned their crook. It is thought the curved cane could have been the brainchild of a German choirmaster, conceived as an ingenious means of keeping fidgety children silent during the nativity service. The first candy canes started out as straight, white sugar sticks. The choirmaster had seen these candies displayed in the window of a candy store and thought they would keep the children quiet. Wondering if parents would not take kindly to his plans to fill their children with diabetes-inducing sugar, the choirmaster asked the candymaker to give them a hook. That way, they would resemble a shepherd’s cane. The crook was then used as a religious symbol to teach children about the three kings and the baby Jesus. The second theory stems from Oliver Cromwell’s reign during the mid-1600s.[6] At the time, there was a prohibition on Christmas decorations. It is said that Christians devised the candy cane as means of secretly identifying one another in the streets of England. The third theory is the simplest: The candy took on a hooked shape to make it easier to hang on Christmas trees. (Occam’s razor, I suppose.) It is worth noting that German Christians had already started to decorate trees with food and candies around the time candy canes were gaining popularity. Nobody truly knows where the modern candy cane originates. However, we do know that confectionary store owner Bob McCormack popularized the process of coloring them. This led to its characteristic red and white stripes. McCormack’s brother-in-law would go on to invent the Keller Machine, automating the process of bending the candy canes.

4 Defecating Nativity Figurines

The caganer : No Catalonia nativity scene should be without one. These tiny figurines squat under the Christmas tree, trousers down, voiding their bowels. Historians aren’t sure about their exact origins, but the tradition may have materialized between the 17th and 18th centuries. Superstition has it that any Catalan who fails to proudly display their own defecating ornament is in for a spell of misfortune. The caganer (aka “the crapper”) is a symbol of fertility, literally fertilizing the ground.[7] While the traditional caganer is represented by a peasant, a number of modern-day variants have come to fruition. Stores sell caganers of the queen of England, Darwin, Freud, Princess Leia, Jon Snow, and Santa Claus.

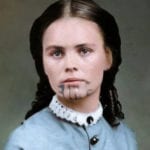

3 The Christmas Witch

Italy has a rather novel take on Christmas in the form of a haggard witch—La Befana. In the same vein as Saint Nick, she whizzes around delivering gifts to giddy children. This spectacular feat takes place on the eve of the Christian holiday of Epiphany, January 5. Riding around on a broomstick, La Befana uses chimneys to sneak into the homes of well-behaved children and deliver her presents. Naughty kids receive sticks or lumps of black coal. The legend of the Christmas Witch has strong religious ties. According to the tale, the Three Wise Men approached La Befana for directions on their way to see the baby Jesus. Although La Befana was unable to provide directions, she did offer the kings a place to rest. Alas, the kindly witch refused the three kings’ offer to meet the Son of God. She would go on to regret her decision, prompting her annual gift-delivering spree.[8]

2 Boiled Sheep Heads And Deep-Fried Caterpillars

Like something inspired from the jungle torture show I’m a Celebrity . . . Get Me Out of Here!, the staple Christmas meal for a number of South Africans includes deep-fried caterpillars. Served as a delicacy parts of Africa, the mopane caterpillar is considered a major source of nutrition. The caterpillar is often collected and gobbled up around the Christmas season. And if entomophagy isn’t your thing, Norway’s got you covered with its smalahove Christmastime meal. Smalahove is a traditional meal in Western Norway and is often served alongside potatoes, rutabagas, and sausages. The main ingredient of the dish is a boiled sheep’s head, replete with eyes and tongue. The appetizing head is cooked with or without the brain, and diners can simply scoop it out with a spoon. The eyeballs, ears, and tongue are all edible parts of the smalahove dish.[9]

1 The Yule Cat

The Yule Cat (Jolakotturinn) is an Icelandic folktale monster that preys on the poorly dressed. The bloodthirsty feline eats people who cannot afford new clothes in the run-up to Christmas. It is thought that the tale was designed to frighten locals into a frenzied work ethic. Slackers, on the other hand, must duke it out with the killer cat—a beast that eclipses even the tallest of buildings. The Yule Cat’s watchful eye gazes into homes, checking to see what gifts children have earned. Badly behaved children do not receive clothes from their parents.[10] The punishment? They are summarily executed at the hands of a snarling cat. And if the horror of the Yule Cat wasn’t enough to turn an Icelandic child into a babbling, neurotic mess, the pet’s horrifying owners certainly will. The cat is accompanied by the giant, mountain-dwelling Gryla and her “Yulemen” progeny. Gryla hunts down naughty kids and hurls them into a stew. Meanwhile, the Yulemen pilfer food, terrify wrongdoers, and deposit rotting potatoes on the windowsills of deviant children. During the 18th century, the tales of the Yulemen became so morbid that the Danish rulers of Iceland forbade citizens from recounting them. There were originally 50 Yulemen, but, over the years, their number dwindled to 13. The pranksters’ temperament shifted, too. They became akin to mini-Santas as the legend began to soften, delivering presents to virtuous children. 13 days before Christmas, an Icelandic child places a single boot on their windowsill. The Yulemen then deliver gifts on each of the 13 nights leading up to Christmas Day. They still have to contend with that cat, though.