Although this list includes as many major international cases as I could find, a list about tampering is bound to be heavy on U.S. content. There are simply far more tampering cases in the United States than there are anywhere else in the world, and the Food and Drug Administration’s records make information about each of them easy to find. Tampering, by definition, is when a product is altered without the manufacturer’s knowledge, and so the tragic cases in China involving melamine in milk powder (2008) and antifreeze in toothpaste (2007) don’t qualify.

What do you do if you don’t want to pay for a $1.40 pack of Jell-o pudding powder? If you’re like Alexander and Christine Clement, a couple in their sixties from Long Island, you buy the pudding, replace the powder with a mixture of sand and salt, and return the package to the grocery store for a refund. The couple struck four stores, purchasing and returning about 50 packages of pudding. The tampering was discovered when a customer who bought one of the fraudulent pudding packages complained to the grocery store, and surveillance video led police to the Clements. The couple was indicted on multiple counts of petty larceny and tampering. Police believe that they weren’t out to harm anyone, they just wanted free pudding, and likely acted under the influence of age-related mental issues.

A diner at a Sizzler restaurant in Queensland discovered pellets of rat poison in her soup, and at another location, the same pellets were found in some pasta sauce. Shortly thereafter, all Sizzler locations across Australia suspended salad bar service. The culprit, who issued no demands or threats of extortion, turned out to be a mentally unstable woman from Brisbane. Nobody suffered ill effects from the rat poison, but a Sizzler spokesperson admitted that the restaurant chain should have notified authorities about the incidents much sooner than it did. The case prompted Queensland lawmakers to draft a law requiring that all food establishments report suspected tampering immediately, or face a fine of $15,000.

A supermarket in Grand Rapids, Michigan, recalled 1,700 pounds of ground beef after 111 people fell ill with nicotine poisoning. Randy Jay Bertram, an employee at the store, had mixed insecticide into the meat in an attempt to get his supervisor into trouble. The victims included about 40 children, a pregnant woman and a 67-year-old man with heart problems. Fortunately, although the amount of insecticide in a quarter-pound burger made from the tainted meat could have been lethal, nobody died or suffered long-term health effects. Bertram was sentenced to nine years in prison and was ordered to pay $12,000 in restitution.

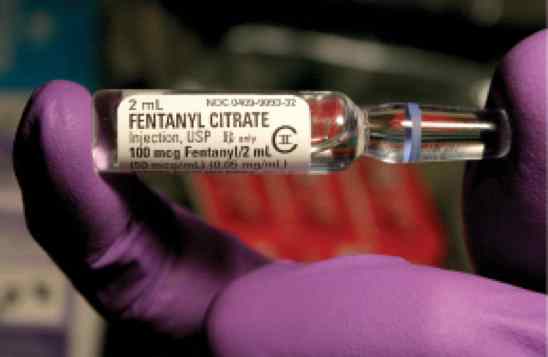

Sometimes tampering can be motivated by the desperation of a drug addict. In 1998, a cardiac intensive care unit in the United Arab Emirates saw an outbreak of Serratia marcescens bacteria. Investigators traced the bacteria to vials of fentanyl, a potent narcotic. A respiratory therapist addicted to the drug had extracted the fentanyl for himself and replaced the liquid with water, which had been contaminated with the bacteria. Cases such as this one regularly surface: in 2009, a nurse at a plastic surgery clinic in Washington State broke open ampoules of Demerol and consumed the contents, then superglued the ampoules back together after refilling them with saline solution. She was sentenced to a year in prison.

About 30 Italians were hospitalized after drinking bottled water contaminated with acetone, bleach or ammonia; small quantities of the poisonous liquids had been injected under the plastic caps. No one claimed responsibility for the acts, but police suspect the tampering could have been the work of anti-capitalist activists or eco-terrorists. Although the perpetrator was dubbed the “aquabomber,” incidents sprang up in more than 20 different cities, leading police to believe that numerous copycats were involved.

The American institution of door-to-door Girl Scout Cookie sales suffered a blow in 1984 when pins, needles and other foreign objects were found in boxes of cookies in at least 17 states, resulting in reports of pierced gums and injured lips. The Girl Scouts suspended cookie sales that year, and, despite the introduction of a new tamper-evident box the following year, sales declined by more than 25 percent, forcing the organization to cut some of its programs. The FBI closed its investigation in 1985, concluding that there was no evidence of organized tampering and suggesting that most of the 800 reported incidents were false alarms or copycat cases.

Baby food seems to be regularly targeted for tampering. Great Britain faced its worst case of food tampering in 1989, when slivers of glass, razor blades, pins and caustic soda were found in products of two of the nation’s largest baby food manufacturers, H.J. Heinz, and Cow & Gate. The scare began with a blackmailer trying to extort $1.7 million from Heinz, and then escalated as copycats capitalized on the initial report. More recently, in 2004, two jars of baby food were found to be contaminated with ground castor beans, which contain trace amounts of the poison ricin. One of the jars contained a note warning that the baby food had been contaminated. The best-known case of baby food tampering, however, is probably the Gerber glass scare of 1986. The Food and Drug Administration received about 140 reports of glass in Gerber baby food and, upon investigation, confirmed 21 cases of tampering, although they were likely the work of isolated individuals. The case is remarkable because it has become a case study for how not to handle a PR crisis. Rather than issue a recall of its products, as its competitor Beech-Nut had done only a week earlier when faced with a similar situation, Gerber seemed flippant and allowed its baby food to remain on store shelves. When Maryland banned Gerber peaches in response to the scare, Gerber sued the state, a move that made the company seem uncaring. Although Gerber has survived the damage to its reputation, and not issuing a recall may have been the financially prudent move, many still consider its response to the crisis unethical and a PR disaster.

On March 19, 1984, two armed, masked men broke into the home of Katsuhisa Ezaki, president of the Glico confectionary company in Japan, tied up his family, and abducted him. The next morning, they contacted the director of the company in Takatsuki city and demanded a ransom of 1 billion yen and 100 kg of gold bullion. Ezaki managed to escape from his captors three days later, but the story didn’t end there. Two months later, Glico began receiving letters from a person or group calling itself “The Monster with 21 Faces” that claimed to have contaminated Glico candies with potassium cyanide. None of the tainted candies were found, and eventually the Monster with the 21 Faces turned its attention to another confectionary, Morinaga. In an open letter set to Osaka news agencies, the Monster told the “moms of the nation” that it had laced twenty packages of Morinaga candy with cyanide. Police discovered tainted packages of Morinaga Choco Balls and Angel Pie in stores before anyone was poisoned; the perpetrators had stuck on labels that read “Danger: Contains Toxins.” Unable to capture the individual or group behind the tampering crimes, the police superintendent of the Shiga Prefecture committed suicide by self-immolation in 1985. After his death, the Monster issued one last letter to the public, commenting on the suicide, and was never heard from again. The case remains unsolved. Disturbingly, eight people in Japan died in 1985 after drinking fruit juice laced with herbicide, but information about this tampering case, despite its much higher death toll, is scarce compared with the coverage of the Glico-Morinaga case.

The four children of the Bergs family in the Netherlands were rewarded with Jaffa oranges for dessert but were alarmed by the fruit’s strange taste. When the family took a closer look, they saw silver globules in the oranges, and the parents rushed the kids to the hospital to have their stomachs pumped. A Palestinian militant group that called itself the Arab Revolutionary Army claimed responsibility, telling the Dutch government that it had injected citrus fruit from Israel with mercury in order to induce panic and disrupt Israel’s economy. The tampering likely took place at a European distribution centre; tainted citrus fruit showed up in Germany, Spain, Belgium, England and Morocco. Another politically motivated, fruit tampering case surfaced two decades later, when the Public Health Inspection service in the U.S. received a call from someone claiming that Chilean fruit had been laced with cyanide, in a campaign to draw attention to the living conditions of the poor under the Augusto Pinochet government. A sample of grapes exported to the Port of Philadelphia tested positive for cyanide, and the Food and Drug Administration detained all Chilean fruit. In the end, 4,781,361 cases of fruit had been examined before Chilean authorities took over responsibility for inspecting fruit before it was exported.

The most infamous case of product tampering is the Tylenol crisis of 1982, in which seven people in the Chicago area died after taking what they thought was extra-strength Tylenol but was in fact potassium cyanide. The case is still unsolved. In addition to the death toll, what makes this case remarkable is that it led to tough anti-tampering laws, as well as a massive shift in how consumer goods are packaged; rarely will you find a packaged food product or drug today that doesn’t have tamper-resistant or tamper-evident seals. Sadly, the Tylenol case prompted a series of copycats. In a 1988 case, Stella Nickell killed her husband with cyanide-laced Excedrin and then put the tainted pills on a store shelf to divert suspicion. Susan Katherine Snow died as a result.