10Joanna Southcott

People who predict the end of the world don’t usually have a lasting impact. As soon as their predictions are proven false, most fade away—apart from Nostradamus, whose ravings are still popular, for some reason. While not as big as him, 18th-century prophet Joanna Southcott exerted a large influence that can still be felt today. Joanna became convinced that she would give birth to the new Messiah, bringing about the end of the world. She even got thousands of people to believe her. In 1814, Southcott announced that she was pregnant at the age of 64. October was set as the due date, but, unsurprisingly, nothing happened. Southcott died soon after her failed prediction. December 27 is her official date of death. A likely apocryphal story says that she died earlier, but her followers kept her body, hoping that she would rise from the dead (she didn’t). Southcott left behind a mystery box, supposedly containing prophecies that would bring about world peace. It could only be opened in the presence of 21 bishops from the Church of England. The box was never opened, but it was X-rayed in 1927. The contents: books, a lottery ticket, a pistol, a purse, a dice box, and a night cap. A century after her death, another woman decided to fund an organization called the Panacea Society based on Southcott’s teachings. It lasted until 2012, when the last religious member died. The organization still exists, but it has been turned into a charity and museum.

9Philip Henry Gosse

A 19th-century naturalist, Philip Henry Gosse had some impressive achievements in his resume. He developed a passion for marine biology from an early age, and this led him to create the first institutional aquarium at London Zoo in 1853. In addition to this, he also wrote several influential books on the subject. Besides his interest in marine life, the man was also quite fanatical about religion. He was a member of the Plymouth Brethren, a Christian sect with very strict rules and moral guidelines that made the Puritans look like the cast of Jersey Shore. One core aspect of this sect was rejecting anything that had to do with evolution, geology, or any other subject that might go against the Bible’s literal word. Keen to put a stop to all that non-Bible malarkey, Gosse undertook what he expected to be his crowning achievement—Omphalos, a book he genuinely thought would bridge the gap between religion and science. The name “Omphalos,” Greek for “navel,” referenced the question of whether Adam had a navel. He did, according to Gosse, but only because God put it there to deceive mankind—that was Gosse’s answer to all current scientific knowledge that went against the Bible. To his surprise, Gosse’s book was rejected by everybody. The scientific community dismissed it as absurd ideas with no proof, and the religious community disliked the implication of a trickster God. Two years later, Darwin published On the Origin of Species, and Omphalos was quietly forgotten.

8John Thomas Looney

Conspiracy theories are nothing new. We might settle on a new favorite one every decade or so, but they’ve been around for a long time as a whole. At the end of the 19th century, there was this growing notion that Shakespeare was a fraud who took credit for works he didn’t write. There were a lot of prominent supporters of this theory, such as Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Sigmund Freud, as well as numerous candidates for who actually wrote all those plays (including Francis Bacon and Christopher Marlowe). However, beginning with the 20th century, one new candidate would stand above all the rest. We’re talking about Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. According to one John Thomas Looney, this man was the real author of all of Shakespeare’s work (including all the stuff written after de Vere’s death). Looney published Shakespeare Identified in 1920, proposing his Oxfordian Theory that caught on like crazy. There was even a movie made about the whole thing a few years ago. Bizarrely, Looney used to be a huge Shakespeare fan. A follower of positivism from an early age, he joined the Religion of Humanity, based on Auguste Comte’s writings. Later on, he joined the British offshoot Church of Humanity, where he became a priest. These people pretty much worshiped Shakespeare and even named a month after him. However, all the attention eventually convinced Looney that only a highly educated noble could write like Shakespeare and found Edward de Vere to be his perfect candidate.

7Henry Prince

It’s never good when people hear voices and assume it’s the word of God. Yet that is what happened with Henry Prince, a 19th-century English reverend who started to believe he was receiving divine instructions to bring about some changes to the Church of England. Unsurprisingly, the Church didn’t react very well to Prince’s ideas and soon defrocked him. Undeterred, the reverend simply went ahead and started his own church in 1846—the Agapemone. The Agapemone (Greek for “abode of love”) had all the tell-tale signs of a modern cult: a charismatic/insane leader, allegations of brainwashing, sex scandals, members surrendering all of their life savings, etc. Bolstered primarily by the financial resources of three wealthy sisters who were Agapemonites, the group developed a significant presence in Somerset. They next spread to other counties such as Suffolk and Brighton and even built a church in London. It didn’t take long for Prince to convince all his followers that he was the embodiment of the Holy Ghost. He even made the bold claim that he was immortal. You could imagine everyone’s surprise when he died in 1899. His second-in-command, John Hugh Smyth-Pigott took over and turned out to be just as mad as Prince, declaring himself the reincarnation of Jesus.

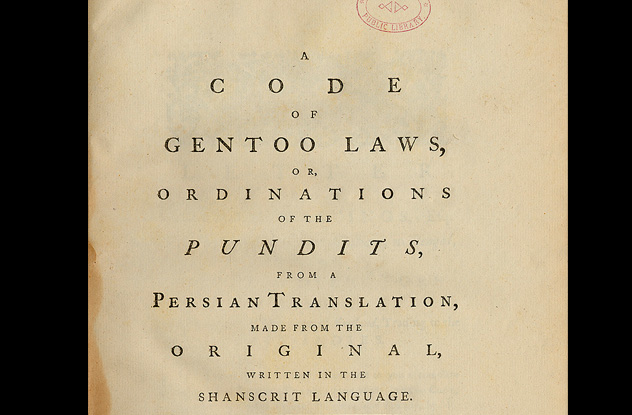

6Nathaniel Halhed

Nathaniel Halhed started off with a promising career as a writer. Born in 1751 and educated at Harrow, Halhed found employment as a writer for the East India Trading Company. While abroad, Halhed became quite a fan of local culture and had the idea of translating the original Hindu legal code into English to facilitate better trade relations with the locals. He had the backing of the East India Company, but there was a problem—Halhed didn’t know Sanskrit. He had to employ local scholars to translate the code from Sanskrit to Persian, and then he translated it from Persian to English. The result was A Code of Gentoo Laws in 1776. The book didn’t really accomplish its diplomatic/mercantile goal, but it did sell well back home and made Halhed famous. He followed it up with a book on Bengal grammar. Things were going well for Halhed until he learned the teachings of Richard Brothers and became a believer of Anglo-Israelism. This hypothesis says Western Europeans are descendants of the lost tribes of ancient Israel. This alone was enough to turn Halhed into an outcast, but he went further and started publishing his own works on the topic. Halhed said a lot of things that didn’t sit well with his peers. His most scandalous assertion was that London was actually the site of the ancient cities of Babylon and Sodom. This got him arrested for criminal lunacy and turned him into a recluse for the rest of his life.

5John Allegro

The most recent entry on this list, John Allegro used to have a successful career, which was ruined by his unconventional ideas. A 20th-century archaeologist, Allegro initially gained fame for his highly publicized work on the Dead Sea Scrolls. He had some controversial notions but was still respected and received a lot of attention in the media. This all changed in 1970. That is when Allegro published The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, still considered one of the most controversial and bizarre books on religion ever written. It’s about linguistics, more or less, with Allegro using etymology from the Bible to support his ideas. He tries to prove that Christianity evolved from ancient fertility cults where people would get high using psychedelic drugs, particularly Amanita muscaria, the “sacred mushroom.” Allegro then concludes that everything in the Bible was made up from visions people had while high on mushrooms. This included Jesus. Suffice it to say, the book evoked a strong reaction. Other scholars immediately rejected the ideas as absurd allegations, and Allegro’s publisher had to apologize for publishing the book due to public backlash. Allegro lost his teaching position at the University of Manchester and became a pariah in literary and academic circles. However, nine years later, he did manage to publish another controversial book about early Christianity titled The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Christian Myth.

4William Whiston

William Whiston was a 17th-century theologian who liked to dabble in science a bit and even received some mentorship from Isaac Newton. From 1694 to 1698, Whiston worked as a chaplain in Norwich, during which he also worked on a book. Like Philip Gosse, Whiston also believed that he could bridge the gap between religion and science by showing that no scientific evidence disproves biblical events like the Great Flood or the creation of the world in six days. The book was called A New Theory of the Earth and was published in 1696. Isaac Newton liked the book and took Whiston on as an assistant while teaching mathematics at Cambridge. When he left, Whiston assumed his position. It was around this time that Whiston became a follower of Arianism (not to be confused with Aryanism), a practice that denied the full divinity of Jesus. These new views cost Whiston his position at Cambridge, as well as his standing in society, but he was undeterred. He founded a new religious group that sought to bring back primitive Christianity and began writing and translating books that were deemed heretical by the general public. His most controversial publication, The Accomplishment of Scripture Prophecies, claimed that many biblical prophecies had been misinterpreted.

3Samuel Wesley

Samuel Wesley, a clergyman with the Church of England, had financial struggles for most of his life. While attending college, Wesley worked as a servitor, which meant he served the rich kids to make some extra money. As a grown-up, his financial woes only got worse as his family got bigger (Wesley fathered 19 children, 10 of which survived after infancy). To make ends meet, Wesley turned to poetry as an extra source of income. Wesley’s poetry was not only highly unusual but also quite controversial coming from a clergyman. Wesley’s book came out in 1685 and was titled Maggots: or Poems on Several Subjects Never before Handled. Like the name implied, Wesley talked about topics that were not usually covered by your average poet (or your average priest). He would write poems about very mundane objects like a tobacco pipe or cheese. Conversely, Wesley would also base poems on very bizarre ideas such as a dialogue between a frying pan and a chamber pot or meeting a bear-faced lady. As if that wasn’t weird enough, the cover for his book of poems was a portrait of himself writing at a table with a maggot on his forehead. Anticipating a potential backlash against his artistic style, Wesley did not put his name on the book, although his portrait on the front cover made it pretty easy to guess the author.

2John Napier

John Napier was an accomplished 16th-century Scottish polymath who made contributions to astronomy, physics, and mathematics. If you ever struggled with logarithms in school, you have John Napier to thank for that. His scientific pursuits aside, Napier was also very interested in theology. He had a particular interest for the Book of Revelations and developed quite an obsession with the apocalypse. Obviously, he became convinced that there was some secret code he could crack to calculate the date to the end of the world. He placed the apocalypse somewhere between 1688 and 1700, but he died in 1617, so Napier never got to find out if he was right or not. It would appear that Napier also had a darker side, as there are many stories about his interest in the occult. They could be all apocryphal, as Napier was a recluse who was always dressed in black, and he kept a black cockerel as a pet (or possibly a familiar). In one story, Napier claimed his rooster could tell when people were lying. He suspected a worker was stealing from him, so Napier had all employees go into a dark room, one by one, and pet the cockerel. This was how the rooster spotted a liar. Unbeknownst to everyone, Napier had covered the cockerel in black soot, so the men came out with dirty hands. The thief, however, fearing the rooster’s mystical prowess, only pretended to pet it and came out with clean hands.

1John ‘Mad Jack’ Alington

Life was nothing but smooth sailing for John Alington. Born into a rich family, he was first educated at Oxford then obtained his priesthood in 1822. Afterward, he inherited a massive fortune, which included, among other properties, over 40 farms in Hertfordshire plus Letchwood Hall. Since he was now the patron of the local church, Alington was asked, as a formality, to assist the local rector, Samuel Knapp. As it turned out, Alington quite enjoyed preaching to the flock, so he took over most services, leaving Knapp only the funerals, which he found unpleasant. Knapp complained to the local bishop, and this got Alington banned from organizing services at the church. Undeterred, Mad Jack started his own church in Letchwood Hall. He had no problem converting the people to his side, since most of them either worked or lived on his property and were quite eager to please. As if that wasn’t enough, Mad Jack would often invite traveling gypsies to attend his services and play music while he distributed beer and brandy to his congregation. The reverend liked to spice up his sermons by covering risque topics—free love was an old favorite. However, he still wanted some modicum of order in his church, so Mad Jack had a shotgun at the ready in case parishioners got too rowdy.