A lot of them suffered professionally due to their outspoken natures. In some extreme cases, they were even suffered physically from the results of their speaking up. And some didn’t live long enough to feel the vindication of being proven correct.

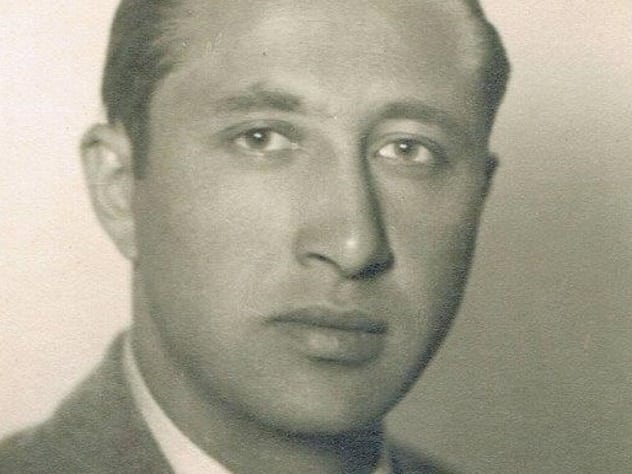

10 The Spy Who Warned The FBI About Pearl Harbor

Dusan “Dusko” Popov was a Serbian double agent during World War II who worked for both MI6 and the Abwehr. He was known for his drinking, gambling, and womanizing, an attitude which helped inspire the character of James Bond. In fact, it was this reputation that led to the FBI mistrusting Popov when he tried to warn them about Pearl Harbor. In 1941, the spy traveled to the United States under the pretense of establishing a network for the Abwehr. He contacted the FBI and told them, among other things, to expect an attack on Pearl Harbor within the year.[1] Popov had two pieces of evidence to back up his claim. One was a communique from a German attache to Tokyo which requested all available information on the successful attack by the HMS Illustrious on the Italian fleet in Taranto. The implication was that the Japanese were planning a similar strike. The other was a German questionnaire on US and Canadian air forces that Popov was supposed to find answers for on behalf of Japan. A third of the questions pertained to the defenses of Pearl Harbor. Popov’s information never made it to the White House or the US military. Some, including Popov, believed this was because FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover disliked and distrusted him. Afterward, Hoover spearheaded a cover-up of the incident which lasted until 1972, when British intelligence declassified the documents.

9 The Scientist Who Campaigned Against Lead Contamination

Clair Cameron Patterson was an American geochemist who, alongside George Tilton, developed uranium-lead dating, which allowed him to calculate the age of the Earth much more accurately than any previous method. During his studies, he also realized that humans were poisoning the environment and themselves with lead. He led a lifetime campaign against lead contamination, particularly as an additive to gasoline in the form of tetraethyllead (TEL). Patterson’s main opposition was Robert Kehoe, a toxicologist who was the number-one scientific advocate for TEL. He was also employed by the Ethyl Corporation as a medical advisor and operated a lab founded by Ethyl, DuPont, and General Motors. Despite his clearly biased position, Kehoe successfully promoted the safety of TEL during the late 1920s, even convincing the surgeon general. Patterson eventually saw his goals accomplished. In the early 1970s, he showed that modern Americans had lead levels between 700 and 1,200 times higher than 1,600-year-old Peruvian skeletons. TEL was initially phased out and then banned altogether. However, this was the result of almost three decades of campaigning, time during which he was ostracized by many within the scientific community. Patterson was called a “zealot” who was guilty of “rabble rousing.”[2] His criticism of the gasoline industry cost him important contracts and positions.

8 The Cyclist Who Knew Lance Armstrong Cheated

Before Lance Armstrong’s fall from grace in 2012, he was seen as one of the most inspirational athletes in history. Some people, however, were never taken in by him. Racer Greg LeMond first raised concerns regarding Armstrong in 2001 and became a pariah of the cycling world for over a decade. LeMond initially criticized Armstrong for his association with Michele Ferrari, an Italian physician who practiced blood doping. He kept silent for several years afterward. Following Armstrong’s miraculous comeback in 2004, LeMond admitted that he was threatened to keep quiet on the matter. He had a line of bicycles licensed and sold by Trek Bicycles, which also happened to be one of Armstrong’s main sponsors. LeMond described the period after his first accusation as “12 years of hell.”[3] He faced a number of lawsuits. In 2008, Trek dropped his brand of LeMond Bicycles because his personal attacks and public comments “hurt the LeMond brand and the Trek brand.” He became persona non grata among cyclists. At a ceremony celebrating Tour de France champions, he was asked to sit and watch from the bleachers even though he’d won the event three times. LeMond’s life got back on track after Armstrong was exposed and stripped of his titles. His line of bicycles was revived in 2014, and LeMond was, once again, the only American to win the Tour de France.

7 The Accountant Who Spotted The World’s Largest Ponzi Scheme

In 1999, Harry Markopolos was a portfolio manager with Boston-based trading firm Rampart Investment Management. Some of his higher-ups heard of a hedge fund manager who was delivering impressive returns on all the businesses that invested with him. They asked Markopolos to look into his technique and see if he could develop a product to replicate his success. That hedge fund manager was Bernie Madoff, and he was running the largest Ponzi scheme in history. Named after con artist Charles Ponzi, the Ponzi scheme is a fraudulent investment method that claims to deliver large profits. In fact, it uses funds from new investors to pay off the profits of earlier ones. The scam is reliant on a steady supply of people sinking money into the operation. It only took Markopolos a few hours to prove that Madoff’s numbers couldn’t be achieved in any legal way. He first went to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to warn them in 2000, but nobody listened. He did it again in 2001 with the same result. In 2005, he compiled a detailed dossier titled “The World’s Largest Hedge Fund Is a Fraud” and presented it to the SEC, but they still only performed a cursory investigation that didn’t find any wrongdoing.[4] It wasn’t until late 2008 that Madoff was finally exposed after his sons called the FBI on him. By then, thousands of families were financially ruined.

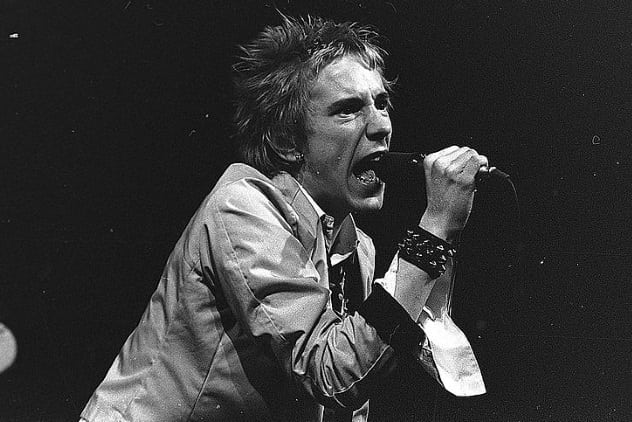

6 The Rocker Who Warned The World Of A Predator

John Lydon is better known as Johnny Rotten, the raucous, controversial front man for the Sex Pistols. He has never been one to shy away from contentious comments, but, according to him, it was one particular interview in 1978 that got him banned from the BBC for “quite a while.” During that show, Lydon said he’d like to kill Jimmy Savile. Savile enjoyed a decades-long career as a TV and radio presenter, mostly with the BBC. During that time, he molested hundreds of children, and only after his death in 2011 was he finally revealed as one of Britain’s most prolific sex offenders. Multiple resignations and apologies came in the aftermath, as there were numerous allegations of a cover-up orchestrated by the higher-ups in the BBC. This is exactly what Lydon talked about almost 35 years prior. He accused Savile of being “into all sorts of seediness.”[5] He also claimed that this knowledge was an open secret within the industry but that they weren’t allowed to talk about it. He concluded that none of the things he said would be broadcasted, and he was right. It wasn’t until 2013 that a complete version of the interview was offered as a bonus track on a re-release of Public Image Ltd’s debut album.

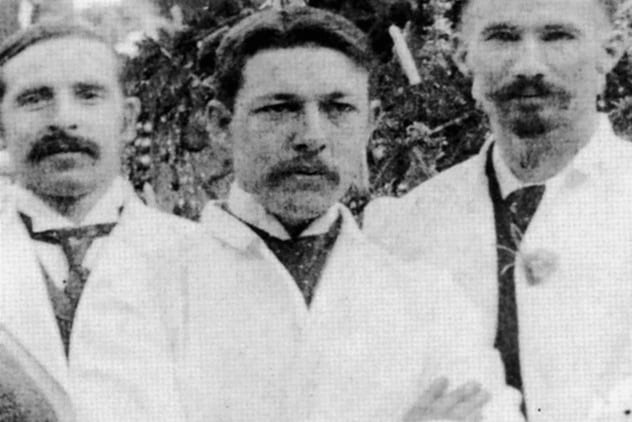

5 The Engineer Who Tried To Prevent A Disaster

During the mid-1980s, Allan McDonald (center above) was the director of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Motor Project for Morton Thiokol, an engineering company contracted to NASA. In January 1986, the Challenger shuttle was getting ready for its tenth mission. McDonald and his team of engineers were concerned that cold weather might adversely affect the mission to the point that he refused to sign the launch recommendation. The higher-ups at Morton Thiokol and NASA did so anyway, with disastrous consequences. McDonald believed that freezing temperatures would stiffen the rubber O-rings and prevent them from creating a tight seal around the rockets. This could lead to burning fuel leaks from the booster joints, which would cause the shuttle to blow up. At first, McDonald managed to persuade his bosses at Morton Thiokol, but NASA officials weren’t convinced without hard data. They insisted on continuing the mission. McDonald refused to sign the launch recommendation, so his boss signed it instead.[6] The Challenger did blow up due to O-ring failure, but not how McDonald expected. At first, he believed it was a problem with the engine or fuel tank that caused the disaster. If the O-rings failed, he assumed the rockets wouldn’t fly at all. What actually happened was that a leak occurred but was almost instantly resealed by aluminum oxides. About a minute into the flight, the winds became strong enough to tear the seal back open and cause the explosion.

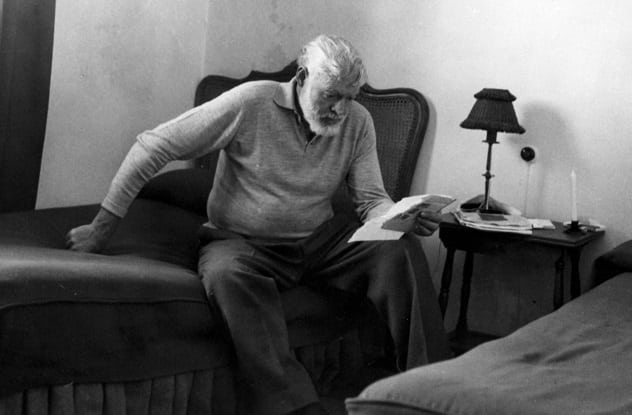

4 The Writer Who Knew He Was Being Followed

Ernest Hemingway was in a bad state, both physically and mentally, during the final years of his life. He suffered from hemochromatosis, was in poor health due to his heavy drinking, and struggled with depression. Therefore, when Hemingway complained that he was being monitored by the FBI, his friends and family dismissed his claims as delusions. Eventually, the author took his own life in 1961, and it wasn’t until two decades later that we discovered that he had been completely right. The truth came out when scholar Jeffrey Myers requested Hemingway’s FBI file under the Freedom of Information Act. The file was over 120 pages and started back in 1942. It was Hemingway’s move to Cuba that brought him to the attention of the FBI. Multiple people have speculated that the FBI surveillance played a role in Hemingway’s suicide. His friend and biographer, author A.E. Hotchner, was one of them. He told the story of when he first found out about Hemingway’s concerns. It was November 1960, about half a year before the writer’s death. They met for a pheasant shoot. Hemingway believed he was tailed on the way to the train station. He insisted on using someone else’s car because he thought his vehicle was bugged. He also thought his mail was being intercepted. When the group saw two people inside a bank, Hemingway claimed they were FBI auditors going over his account. This all happened just during the ride from the station to the writer’s house. Hemingway described his life as “the goddamnedest hell.”[7]

3 The Doctor Who Pioneered Immunotherapy

Today, William Coley (center above) might be known as the “Father of Immunotherapy,” but he faced an uphill battle in his own time to prove that purposely infecting patients with disease can be a viable treatment for cancer. Back in the late 19th century, surgery to remove tumors was considered the only efficient method to fight cancer. But Coley, then a young doctor at New York Hospital, read dozens of stories of patients who had their large, inoperable tumors either shrink or disappear completely after contracting other dangerous, potentially fatal ailments. Not one to waste time, Coley found Zola, an Italian immigrant with a giant tumor on his neck obstructing his pharynx. Coley infected his patient with erysipelas, which liquefied his tumor. Over the decades to come, the physician treated hundreds of other people and even mixed up his own batch of Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens, still known today as Coley’s toxins.[8] The medical world wasn’t convinced by Coley’s efforts. It didn’t really help that he wasn’t the conscientious, methodical type. His patients reacted unpredictably because Coley concocted 13 different variations of his mixture. Some of them died from the infection, while others never caught it at all. Coley couldn’t even explain why his method worked because there was no link, at the time, between microorganisms and cancer. Radiation therapy was also emerging as a cancer treatment around that time. It was much more readily accepted by leading experts, including James Ewing, who was Coley’s boss at New York Hospital and one of his biggest critics. It wasn’t until 1935 that the American Medical Association reversed their position on Coley’s toxins. Coley died less than a year later.

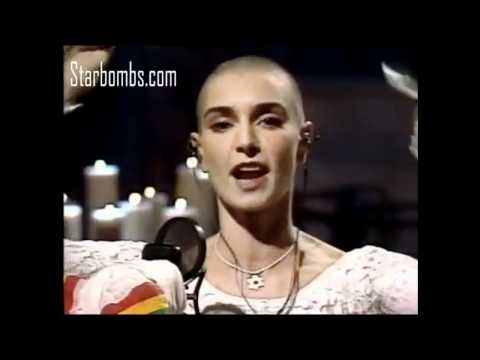

2 The Singer Who Warned Of Abuse Within The Catholic Church

On October 3, 1992, Irish singer Sinead O’Connor appeared on Saturday Night Live (SNL) as a musical guest. She performed an a cappella version of Bob Marley’s song “War” with modified lyrics to make it about sexual abuse instead of racism. At the end, Sinead held up a picture of Pope John Paul II to the camera, tore it to pieces, and said, “Fight the real enemy.”[9] The crowd was stunned. Backstage, SNL executives didn’t know how to react other than not pressing the “Applause” button. O’Connor was criticized by politicians and celebrities and got booed off stage at concerts. The following week on SNL, host Joe Pesci presented a photo of the pope taped back together. Pesci also said that, if he had been there, he would have given O’Connor “such a smack” to roaring cheers and applause from the audience. Nowadays, scandals in the Catholic Church have become commonplace. So is criticizing the Vatican for not only failing to stop these abuses but actively working toward covering up the crimes of its priests. Thousands of victims have been uncovered all over the globe, going back decades. In the early 1990s, though, such criticisms were out of the public consciousness. O’Connor became vilified for her actions, and her career suffered for it.

1 The Doctor Who Tried To Save Mothers

For his efforts in pioneering antiseptics in medicine, Joseph Lister was named the president of the Royal Society, earned the undying respect of his peers, and was given a baronetcy by Queen Victoria. For his efforts trying to do the same thing, Ignaz Semmelweis was ridiculed by the medical community, dismissed from his job, and committed to an insane asylum. In 1847, Semmelweis was working as a professor’s assistant at the maternity clinic of Vienna General Hospital. He came to the conclusion that if the medical staff washed their hands, they could significantly curtail the spread of puerperal fever. He had the interns wash with chlorinated lime solutions, and this reduced the incidence of fatalities caused by the fever from ten percent to one to two percent.[10] Despite the results, his peers were not impressed with Semmelweis’s hypothesis. Unlike Lister, the Hungarian physician didn’t have Louis Pasteur’s advances into microbiology to explain why his idea worked. He just knew it did, but other doctors refused to believe that they were responsible for most cases of puerperal fever. Eventually, Semmelweis lost his position at the hospital and became so scorned in Vienna that he returned to his native Hungary. Almost two decades later, Semmelweis was an angry, bitter man. He wrote furious open letters to obstetricians, calling them murderers. He began drinking and experienced mood changes. In 1865, his family committed him to an asylum, where he died after two weeks. Even today, people question if Semmelweis suffered from a disease like Alzheimer’s or syphilis or if he simply broke down due to the stress of his work.