10Robert Murat

Life was good for this British property consultant. He lived comfortably in southern Portugal, enjoying his work, the mild climate, decent prices, and delicious food. Then, the story about the disappearance of little Madeleine McCann swept the globe, and the notoriously sensationalistic English tabloids smelled blood—Murat’s, to be precise. A British journalist convinced the Portuguese police to include Murat on the list of suspects with a variety of wild accusations, including tips that Murat had been seen outside the McCanns’ vacation home, incriminating DNA had been found, and his home contained a secret chamber. He was soon acquitted when the claims were all proven to be false. Even though Murat’s name had been cleared, his credibility was destroyed, and his personal and professional lives were left in utter shambles. He later sued the tabloids that had hounded him and his family to the tune of £600,000 in libel settlements, but even now, he still feels haunted by the accusations.

9Dmitri Shostakovich

In the Soviet Union, the press was controlled by the state, so being targeted by a media campaign really meant being an enemy of the state. Dmitri Shostakovich, a brilliant composer, was first deemed “decadently bourgeois” in the age of the Great Purges, when his opera Lady Macbeth in the District of Mtsensk was criticized as “muddle instead of music.” At the time, many of his friends and relatives had been sent to the death camps, some never to return. Shostakovich needed to be careful to toe the Party line. Shostakovich redeemed himself first with his “Symphony No. 5” and then during World War II, when the siege of his hometown inspired the name of his magnum opus, “Symphony No. 7” a.k.a. “Leningrad.” But Shostakovich’s genius could not be kept in check by the Party. His interest in Western “formalist” and Jewish music during another bout of Stalinist paranoia meant a second fall from grace. He was not redeemed until he joined the Communist Party in 1960, well after Stalin’s death.

8Steven Jay Hatfill

Days after the September 11 terror attacks, a series of letters containing anthrax spores targeted at senators and members of the media showed up within the US Postal Service. As a result, 17 people were infected by anthrax, five of whom died. After a desperate scramble to link the letters to jihadism turned up nothing, the suspicions of the press fell upon Native American biologists, especially those involved in biological warfare research. Steven Jay Hatfill had lived in Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe) during an outbreak of anthrax infection, which influenced him to research its effects. Subsequently, circumstantial evidence picked up by amateur detectives contracted by the press, especially The New York Times and Vanity Fair, pointed at him. The wannabe sleuths convinced the FBI to take their suspicions seriously, unleashing a Kafkaesque hell upon Hatfill. The charges, of course, were found to be baseless. In a series of lawsuits, Hatfill was awarded $5.8 million from the US government and undisclosed sums from The New York Times and Vanity Fair. The case is currently still unsolved and will likely remain so, as the top suspect, Bruce E. Ivins, has committed suicide.

7Diego P. V.

This Spanish man from the Canary Islands was falsely accused of abusing and killing his girlfriend’s three-year-old daughter. In a textbook case of yellow journalism, he was not even given the benefit of the presumption of innocence. His face was shown prominently on the front page of national newspapers, under headlines such as “The gaze of the killer of a three-year-old-girl.” This was a practically unprecedented event in Spanish journalism, which had previously been known for its restraint, always careful to use the word “alleged” (presunto) in its coverage of criminal cases. Their new fondness for smear tactics backfired, since Diego was proven innocent after the girl’s autopsy revealed that she had died accidentally due to a head injury from falling off a swing.

6Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Sakharov was a brilliant Soviet nuclear physicist, but he is better known for his campaigns for human rights and freedom of speech in the USSR. When the Brezhnev government started a repression campaign against fellow scientists and then intellectuals in general, he started writing open letters that were increasingly critical of the Soviet state. In 1970, Sakharov founded the Moscow Committee for Human Rights. That prompted the state to initiate a media campaign of denunciation in 1973, smearing his good name and accusing him of treason. The campaign also targeted Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. One of the prominent Soviet citizens who signed some of the letters was Dmitri Shostakovich, probably under duress and already in delicate health. Nothing deterred Sakharov. He went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975, but he didn’t stop there. His criticism of the invasion of Afghanistan led to his internal exile to Gorki (now Nizhni-Novgorod, Russia), which was lifted at the onset of Perestroika.

5John Stoll

John Stoll was one of the people found guilty in the infamous Kern County child molestation case that started the daycare child abuse hysteria of the ’80s. He was given the longest sentence of all the defendants. His ex-wife was furious about sharing custody of their son, whom Stoll was accused of molesting. Wild accusations of satanism and debauchery were soon fabricated and spread by the media. Fueled by the false testimony of other misled children, he spent 20 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. He was ultimately exonerated and awarded $700,000 in compensation.

4Dolores Vazquez

After Dolores Vasquez parted ways with Alice Hornos, she thought the worst she would experience was heartache. After Hornos’s daughter went missing, however, she found herself in the middle of a destructive media circus on trial for murder. Although she adamantly maintained her innocence and even provided an airtight alibi, she was convicted of the murder of Rico Wanninkhof by a popular jury. While Vasquez was in prison, however, another young girl disappeared. After her body was discovered, it was found that the DNA evidence at the scene matched that near Wanninkhof’s body. The real killer of both girls was identified as a man named Tony Alexander King, and Vasquez’s conviction was overturned. She now lives a quiet life in Essex, England.

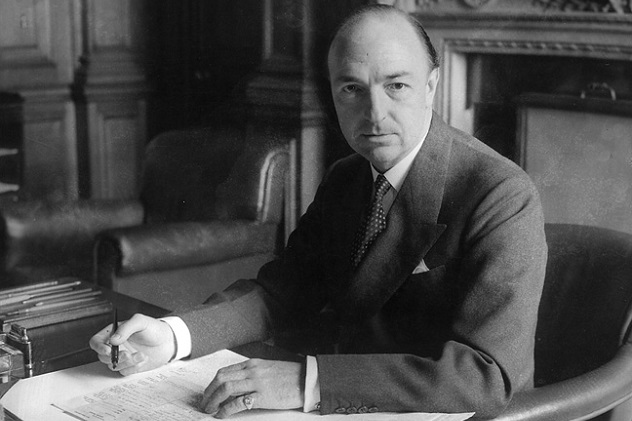

3John Profumo

In 1963, British politician John Profumo was the Secretary of State for War and a member of the Privy Council when scandal arose. It was discovered that the respectable war veteran, married to film star Valerie Hobson, had an affair with a woman named Christine Keeler. Since Keeler was also the lover of senior naval attache at the Soviet Embassy and GRU agent Yevgeni Ivanov, the British public was concerned that Profumo might have shared government secrets with Keeler. Although he swore that no such secrets had been shared, he was forced to resign. Profumo went on to lead a quiet life of charitable work in London’s East End for 40 years, cleaning toilets in a soup kitchen that he later managed. He was ultimately decorated by the queen for his charity and attended Margaret Thatcher’s 80th birthday party as an honored guest.

2Thomas Kossmann

For most of his career, this German-born Australian bone surgeon was a respected figure in the medical community. That all changed in 2008, when he was accused by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and other outlets of “harvesting” his patients for money, charging for unperformed operations, and performing unnecessarily risky surgeries that endangered lives. The probable spark for the case was internal politics: Kossmann was a shooting star in the medical establishment and wanted to reform the management of the Alfred Hospital. In the end, Kossman was acquitted of any malpractice. After he was cleared by every investigation, he demanded full apologies from the media, and his life was put on hold for three years while he endured lawsuit after lawsuit. The Alfred Hospital dropped charges against him and apologized, and he went on to fund his own clinic with the proceeds of the settlements he was granted.

1Gino Girolimoni

Gino Girolimoni was a photographer from Rome who was accused of raping and killing several young girls in the 1920s. The horror of the crimes was compounded by the tender ages of the victims, the oldest of whom was six and the youngest of whom was barely two. The pressure of the recently established Fascist regime to find a culprit and the righteous rage of the Roman populace made things worse for Girolimoni, who was relentlessly hounded by the press. Luckily, a by-the-book cop named Giuseppe Dosi found several inconsistencies in the accusations. Subsequently, Girolimoni was acquitted, and the crimes remain unresolved. Girolimoni’s story was immortalized on film in a 1972 movie about the case, Girolimoni, il mostro di Roma (or The Assassin of Rome). Nevertheless, he died destitute, mourned by just a few close friends. His name is still synonymous with “pedophile” in the Roman vernacular. A. J. Simonson is a lowly engineering student who strives to be an Oompa Loompa of technology. History, languages, politics, and economy are side interests to his main passion: cars and planes.