10 Operation Downfall

Code-named Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of Japan is a popular source of inspiration for alternate history books, comics, and even board games. Operation Downfall has also served an important political function, justifying the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by contrasting the real-life casualties with the projected loss of life in an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. However, nuclear policy analyst Ward Wilson disagrees. The timing of Japan’s surrender doesn’t seem to match up entirely with the bombings. Plus, Japan suffered far more destructive attacks from conventional bombs earlier on, and these didn’t have much of an effect. So in addition to knowing about the existence of atomic bombs, the Japanese were already accustomed to that level of destruction and weren’t fazed by the loss of life. The Japanese military hoped the high cost of an invasion would impel the Americans to offer better surrender terms. However, they were worried about Soviet movements. The Russians had crushed Japanese forces in Manchuria and seized Sakhalin Island in order to prepare for an invasion of Hokkaido. Fighting two superpowers wasn’t possible, and furthermore, while a potential American invasion was still months away, Soviet forces could be in Japan within 10 days. If Ward’s assessment is true, then Operation Downfall was never going to happen. Either the Japanese were always going to surrender due to pressure from both directions, or the Soviets were going to beat the Americans to the punch, turning Japan into a communist satellite state.

9 Operation Sealion

The Nazi plan for the invasion of Great Britain, also known as Operation Sealion, is such a commonly proposed alternate history scenario that it’s now widely reviled by fans of the genre. Nevertheless, Operation Sealion is the subject of everything from books and movies to TV shows and games. After all, it’s a compelling and disturbing scenario, a situation where the Germans occupy the Channel Islands of Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, and Herm. It provides a tantalizing glimpse into what could’ve happened, but it’s highly unlikely—if not impossible—that it would have ever come to pass. One of the most comprehensive arguments against Operation Sealion’s feasibility was presented by the late Alison Brooks. She explained how the Royal Navy was far superior to Germany’s Kriegsmarine, making any crossing of the English Channel impossible. She also points out how attempts to improvise solutions with pontoons and rafts were doomed to failure. There was also the problem of resupply, and the fact that the proposed landing area was teeming with British and Commonwealth routes. It was also vulnerable to merciless RAF bombings which the Luftwaffe couldn’t prevent. Brooks even went so far as to say the only way a German invasion of Great Britain could’ve succeeded would’ve been through the intervention of “alien space bats.” These “ASBs” have now become shorthand in the online alternate history community for a magical, hand-waving force allowing impossible scenarios to take place. Brooks’s analysis was amateur, but more scholarly researchers have backed her up. Hitler had underestimated the British and hadn’t prepared a solid strategy for invading the British Isles. While the Wehrmacht was dominant on the European continent, neither the Luftwaffe nor the Kriegsmarine could hold a candle to the Royal Air Force or Royal Navy. Thanks to the bickering among the various branches of the German military, coupled with British tenaciousness and radar advantage, the plan was always impossible.

8 Zheng He Discovers America

The Chinese admiral Zheng He was an impressive figure, leading a treasure fleet on a diplomatic mission from the Ming dynasty through Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, and even Africa. However, the idea that Zheng He could’ve reached the American continent has long been popular in alternate history circles where it’s considered something of a cliche. And thanks to the nutty author Gavin Menzies, this theory has been popularized in revisionist history as well. (Full disclosure: This author even played with the idea as a misguided youth, which can be seen in a horribly embarrassing piece of juvenilia that is still online somehow. Don’t judge.) There are reasons to believe that if Europeans had never entered an Age of Discovery, the Americas would’ve eventually been discovered by the Chinese or another Asian civilization. However, there is no chance Zheng He ever got there. A supposed 15th-century Chinese map depicting the Americas has been declared a hoax, even by Chinese scholars who would have an interest in claiming its veracity if there was any doubt. The details on the map—including the coastlines of Alaska, Central America, Australia, and New Zealand—would have required centuries of exploration and cartography of which there is zero historical record. For the Chinese to discover the Americas, they would’ve had to set off into the Pacific Ocean on a massive journey without any reason. Due to geography and wind patterns, it wasn’t too difficult for Europeans to reach the Americas. The Pacific, however, is huge. What’s more, the Chinese had no compelling reason to try such a voyage. They knew all the significant countries of note were in the south and west. They were going to follow existing trade routes and monsoon winds, just as all traders in the Indian Ocean trade system did. A voyage east into the deep blue would’ve been pointless, unprecedented, and completely suicidal. Historian Ian Morris put it best when he said: Europeans’ most obvious geographical advantage was physical: the prevailing winds, the placing of islands, and the sheer size of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans made things easier for them. [ . . . ] [Furthermore] in the fifteenth century economic and political geography conspired to multiply the advantages that physical geography gave western Europe. Eastern social development was much higher than Western, and thanks to men like Marco Polo, Westerners knew it. This gave Westerners economic incentives to get to the East and tap into the richest markets on earth. Easterners, by contrast, had few incentives to go west. They could rely on everyone else to come to them. So if the Chinese didn’t even bother to sail to Europe, why would they fund an expensive expedition westward to nowhere and for no reason?

7 Invasion Of The Mainland United States

An invasion of the mainland United States by a foreign power has been a recurring fear throughout American history. Perhaps the most famous example is Red Dawn, a 1984 film which pits Midwestern freedom fighters against Soviet occupation forces (not to mention its 2012 remake where the US is invaded by North Korea). Other potential invading forces proposed over the years have included Imperial Germany under the Kaiser, Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and the perfidious Canadians. Watch this video on YouTube However, none of these scenarios had any real chance of succeeding, largely due to the massive military advantage of being protected by two massive oceans on each coast. While Kaiser Wilhelm II dreamed of neutralizing the US Navy and sending German troops to Boston and New York, the Imperial German Navy was simply not up to the task. Making things worse, any German troops would be far from home and facing a furious country led by Theodore Roosevelt, a man unlikely to take it lying down. The Axis powers of World War II came up with a number of schemes to invade the US, schemes that largely required the construction of long-range bombers to soften the enemy. These plans included Japanese invasions through Alaska, California, or the Panama Canal, coupled with German attacks on the East Coast as a distraction. Alternatively, there was talk of the Japanese military linking up with the Germans in the Atlantic to attack the US through Canada, the East Coast, or Brazil. But for all their maps and plans, neither the Germans nor the Japanese possessed the force extension capacity to make any of it remotely possible. The Soviets might have had a shot at invading Alaska with paratroopers and bombers, probably while in the process of invading Western Europe, which led the FBI to recruit ordinary Alaskans into a guerrilla force of spies. But an invasion of the mainland was considered highly unlikely to be even attempted, with attacks on Canada and the US in a war scenario limited to bombing runs and sabotage. Vice even conducted an interview with military analyst Dylan Lehrke on the possibility that the combined armies of the rest of the world could invade and conquer the US. According to Lehrke, America’s nuclear deterrent couldn’t be realistically disabled since it’s based on a triad of land, air, and sea delivery systems designed for counterstrike ability. Even if the nuclear arsenal was magically rendered inert, the world’s combined air- and sealift capabilities wouldn’t be enough to gain a foothold on the US mainland, necessitating an invasion through Canada or Mexico instead. But the technological, logistical, and geographical advantages of the United States guarantee that any invasion—even by everyone else on the planet—is doomed to fail.

6 Lee Seizes Washington

The American Civil War is a popular area of alternate history speculation, and the Battle of Gettysburg is one of the biggest points of divergence from our own timeline. Many believe that if General Robert E. Lee had been victorious, he could have easily threatened or taken Washington, DC, and forced the Union to surrender. In his contribution to the 1931 collection of essays called If, or History Rewritten, Winston Churchill suggested that the Battle of Gettysburg would’ve been won by the Confederates if cavalry officer Jeb Stuart hadn’t made an ill-advised attack on the Union’s rear at a critical moment. In Churchill’s scenario, the Army of Northern Virginia takes Washington within three days, and then somehow manages to declare the end of slavery, securing British support and forcing President Lincoln to recognize an independent Confederacy. Meanwhile, the classic 1953 alternate history novel Bring the Jubilee sees Gettysburg as the turning point in the “War of Southern Independence.” By the early 20th century, the US is a backwater in a world divided between the Confederacy and the Germanic Union. However, American history professor Gary W. Gallagher argues that Gettysburg and other battles occurring in 1863 were not actually vital turning points in the war. Instead, they have developed an exaggerated sense of importance due to the habit of looking backward at history, a tendency he calls the “Appomattox Syndrome.” The defeat at Gettysburg didn’t impact Confederate morale or General Lee’s reputation. Conversely, Lincoln was said to have viewed it as an opportunity squandered, thanks to Union General Meade who let the Southern army escape, thus raising fears the war could be indefinitely prolonged. But while a Confederate victory at Gettysburg would’ve been a political disaster for Lincoln and would absolutely cause military problems for the Union, there was little chance that Lee would’ve captured Washington, which was well defended with forts and guns. Historian Richard McMurray agreed with that assessment, asserting that while 1862 was the high point of Confederate fortunes, things were very different in 1863. The South was losing everywhere except in Virginia where there was a stalemate. Gettysburg developed a mystique because it involved the two most famous armies of the Civil War, was the bloodiest battle, and was fought in a free state near Northern populated centers. But compared to other battles like Shiloh, Chickamauga, Vicksburg, and General Grant’s 1864 campaign, Gettysburg was “a great defensive victory for the North but that is all it was.”

5 Muslim Victory At Tours

It’s a romantic and popular image. The Islamic expansion had roared out of Arabia, conquering the Middle East, Persia, North Africa, and Spain. The Muslim cavalry stood ready to expand north into France and snuff out Western civilization with endless jihad. Only when Emir ‘Abdarrahman sent an army to assault the city of Tours, his jihadis were decisively defeated by Charles Martel’s Frankish forces at Poitiers. Historian Edward Gibbon called Martel the savior of Christendom, claiming that without him, “The interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.” To Martel’s contemporaries, however, it was hardly so significant. At the time, the entire region was wracked with similar battles, usually between Christian princes as the Carolingians fought to establish control over Aquitaine. There had been many battles fought between Muslims and Christians in southern France, some won by each side. One chronicler even blamed the Christian Duke of Aquitaine, Eudo, for causing the battle by seeking to ally with the Muslims north of the Pyrenees in Septimania who themselves were seeking independence from the Arab rulers in Spain. Many of the battles fought by Charles Martel were as much aimed at troublesome Christian princes as they were at Muslim interlopers who were relatively few in number. Most contemporary historians were unimpressed by the Islamic threat to southern France and the Mediterranean, seeing them as pagan barbarians and a nuisance but not an existential threat. There were a number of other factors which led to the halting of the Muslim advance into Western Europe. While they fought in the name of religion, the Muslims at Tours were chiefly concerned with easily acquired plunder. The Franks proved too much of a nut to crack, especially considering there were more easily acquired riches elsewhere. The climate of central France may have been uncongenial to the Arab and Berber invaders who were also reaching the limits of their manpower. Meanwhile, the invasion of Spain was not even complete as resentful Visigothic princes in the northwest remained resistant to the Islamic invaders. While a Muslim victory at Tours would likely have had some significance and possibly led to a longer period of Islamic forays into southern France, it was only one of many battles fought in the region during this time period. In fact, it’s likely the Muslim tide would’ve died off regardless, absent larger historical divergences.

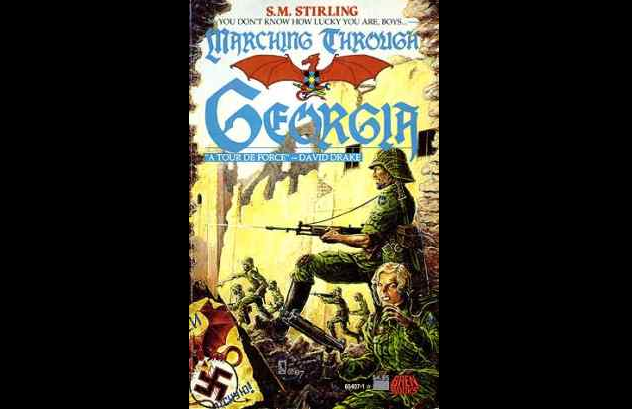

4 Draka

One of the most popular and successful alternate history series is The Domination of the Draka by S.M. Stirling. The plot involves British officer Patrick Ferguson, the man who invented the breech-loading rifle, surviving the American Revolutionary War. At the same time, the Netherlands attacks the British during the conflict. In the aftermath, Loyalists from America are settled at the Cape of Good Hope in a colony called Drakia, so named after Sir Francis Drake. Over the next few centuries, the Draka develop into an aggressively militaristic, xenophobic, and racist society that dominates the African continent, eventually defeating the Nazis and Soviets to rule Eurasia. The Draka become a Nietzschean superpower of atheistic, bisexual sadists. The series ends with the American-led democratic nations fleeing the planet which is now under the complete control of the Draka. All other non-Draka left behind are reduced to servitude. The series has always had a core of passionate fans, though even Stirling confessed to being disturbed by “people who wanted to move” to his fictional country. However, the series has an equal number of detractors who believe that the descriptions of the rise of the Draka are unlikely at best and creepy wish fulfillment at worst. An online cottage industry has even sprung up where people write their own takes on the Draka timeline, stories that usually involve more realistic setbacks and failures. Ian Montgomery wrote in detail on the implausibility of the Draka timeline. Britain is unlikely to have allowed one of its colonies to develop into an autonomous slave state in a time period when attitudes toward slavery had turned decidedly frosty in Great Britain. The Draka expand quickly and develop their technology and industry rapidly, despite having an economy based on slave labor with the majority of the population remaining uneducated. The Draka are depicted as militarily superior in all circumstances, and they’re never attacked by other powers. All in all, it’s a constant string of impossible good luck. John Reilly argued that while the Draka were an extension of other societies that existed historically—like apartheid South Africa and the Confederate States of America—societies based on slave economies were less economically dynamic. A servile economy where a minority dominates would find it difficult to maintain an expanding economy without tearing itself apart from internal contradictions. One explanation is that the Draka are insane (which is actually implied), and Stirling uses genetically engineered subspecies to explain the continued domination of the human race by the Draka in later novels.

3 Japanese Invade Hawaii

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, fears of a full-blown invasion were so high that US currency in Hawaii was emblazoned with the state’s name in block letters. This way, it could be rapidly devalued if the islands were taken by the Japanese. Harry Turtledove explored the idea of a Japanese invasion in his Day of Infamy series in which the Japanese infantry lands on the islands and forces the US military to surrender outside Honolulu. But while fears of such an eventuality were real, the actual risk of an invasion of Hawaii was negligible. One commonly proposed scenario involves the Japanese scoring a decisive victory at the Battle of Midway, wiping out most of the US carrier fleets, thus allowing the Japanese to seize Hawaii in one fell swoop. The problem is that such an undertaking would’ve been nearly impossible and incredibly risky. By early 1942, there were 100,000 US troops on the islands who would’ve been well-prepared and possessed better knowledge of the terrain. Unlike the Japanese invasions of Malaya and Luzon, the strategic targets were in a compact and easy-to-defend area. The Japanese needed to send at least 60,000 troops to have a hope of victory. However, they didn’t have the logistical capabilities by sea or sufficient air superiority to pull it off. Even if the Japanese had invaded right after the attacks at Pearl Harbor, the only way an operation of that size could have succeeded would’ve been by taking troops and hardware away from the active theaters in China and Southeast Asia. As securing the resources of the latter was one of the main reasons for going to war with the West in the first place, such an operation would’ve been detrimental to the Japanese whether it succeeded or failed. Writer Dale Cozort explored the many issues facing a Japanese invasion of the Hawaiian Islands. The Japanese would’ve lacked sufficient ordinance, fuel, transport ships, and daylight. US troops were all over the island, and they could be easily reinforced from the US mainland. The Japanese, on the other hand, would have to commit their carrier fleets to support the costly invasion, allowing the US Navy to take control of the central Pacific unopposed. The loss of planes to US anti-aircraft guns and fighters would’ve been crippling, and even in a damaged state, the battleship guns in Pearl Harbor would’ve devastated any landing force. In short, Cozort says, “The Japanese got in a good sucker punch but that wouldn’t be enough to overcome the logistical and coordination barriers to a successful invasion of Hawaii.”

2 Nazi And Japanese Nukes

Axis victory scenarios are often justified by having either Nazi Germany or Imperial Japan develop an atomic bomb before the Allies do. While it’s true that both Axis powers were interested in atomic weapons, it’s highly unlikely they would’ve developed such weapons before the Allies ground them into dust. In 2005, German historian Rainer Karlsch caused waves when he claimed Nazi Germany had tested three nuclear weapons in March 1945, but there is little to no proof of these claims. The American Manhattan Project was a huge undertaking, involving 125,000 people, the equivalent of $30 billion, and an R&D area the size of Frankfurt. By contrast, the German nuclear weapons program was overlooked and barely funded by a handful of physicists. The idea of a fission bomb had been developed as part of the combined research of radiochemist Otto Han and the Jewish Austrian physicist Lise Meitner who’d fled when the Nazis invaded her country. In 1939, prominent German physicists formed the Uranverein (“Uranium Club“), led by Werner Heisenberg, to investigate the possibility of atomic weapons. But the German government was only vaguely interested, and there was no centralized effort like the Manhattan Project. Responsibility for the project passed through various departments. Meanwhile, nuclear physics as a discipline suffered under an authoritarian regime prone to disparaging “Jewish science.” Disasters like the destruction of crucial heavy water production facilities, courtesy of Norwegian guerrillas and Allied bombers, also slowed the program down. By the time the Nazis realized the true potential of atomic weapons, they were way behind in the game. In 1944, the German efforts to produce a nuclear reactor were centered in a wine cellar in the small village of Hechingen. Most of the obstacles that stood in front of the German nuclear program boiled down to the very contradictions of the Nazi state. While Germany could possibly have beaten the US to an atomic bomb in the 1940s in a different scenario, it wasn’t going to do so under the National Socialist regime. As for the Japanese atomic weapons program, little is known due to the fact that many documents were burned at the end of the war. However, they were late to the game as well. The Japanese were only at the very elementary stages of research when they ended up on the receiving end. It is claimed that by 1944, the Japanese had a thermal diffusion device that would’ve allowed extraction of uranium-235, but American bombers destroyed their facilities. The chief problem, though, was that Japan didn’t have enough supplies of uranium to pursue a serious nuclear program. In May 1945, a Nazi submarine was captured transporting 550 kilograms (1,200 lb) of uranium oxide to Japan, and this material ended up in the very bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While the Japanese might have eventually gotten their act together, their nuclear program was too rudimentary and prone to setbacks. For either Axis power to develop nuclear weapons, they would have needed time and resources they didn’t have, and they probably wouldn’t have been able to throw anything together until around 1950 anyway.

1 Peaceful Middle East Without Islam

Quite a few people believe that many of the historical and current conflicts around the world can be blamed on the theological teachings of Islam. Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington used this as a central point in his “Clash of Civilization” thesis, in which he argued that the major geopolitical conflicts of the 21st century would be between differing civilizations rather than competing ideologies or interests. He emphasized the bloody conflicts between Muslims and non-Muslims in the Middle East, as well as South and Southeast Asia, concluding that, “Islam has bloody borders.” The obvious conclusion from all this is the idea that if there was no Islam, we would live in a more peaceful world. However, history professor and former CIA analyst Graham Fuller is unconvinced. He argues that the geopolitical fault line between the Middle East and the West is due to “deep-rooted conflicts that still exist over ethnicity or economics or warfare or armies or geopolitics [that] really don’t have anything to do with Islam, and indeed, existed long before Islam came into existence.” For example, the Zoroastrian Persians and pagan Greeks were fighting bloody wars over the Middle Eastern territory that would later be fought over by Christians and Muslims, for many of the same reasons. Even if the Middle East was predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christian, there would’ve been just as much cultural and political impetus for bloody conflicts as there was in our timeline, as evidenced by the bloody Frankish sack of the Christian city of Constantinople in 1204. A predominantly Christian Middle East would’ve been no more accepting of Western colonialism or oil companies, and the economic incentive for Europeans to seize control of resources and populations in the region would’ve been the same. Without Islam, it’s just as likely the conflict between the Middle East and the West would be framed in different terms. Perhaps the division would be between Latin and Eastern schools of Christianity. The geopolitical realities and conflict logic would’ve meant that the borders of the Middle East would’ve been just as historically bloody. Only in this timeline, the bloodshed would have to be blamed on something other than Islam. David Tormsen is one implausibility of our timeline. Email him at [email protected].