What people have come up with over the years are a series of names, most of whom were either professional or amateur archaeologists in their own time. Some have proven controversial, such as the occultist and unwilling Nazi scientist Otto Rahn, while others seem far-fetched. This list is an attempt to shed light on Indy’s ancestors and maybe even the man (or men) who gave Indiana Jones the breath of life. Some names might be familiar to you, while others may be a complete mystery.

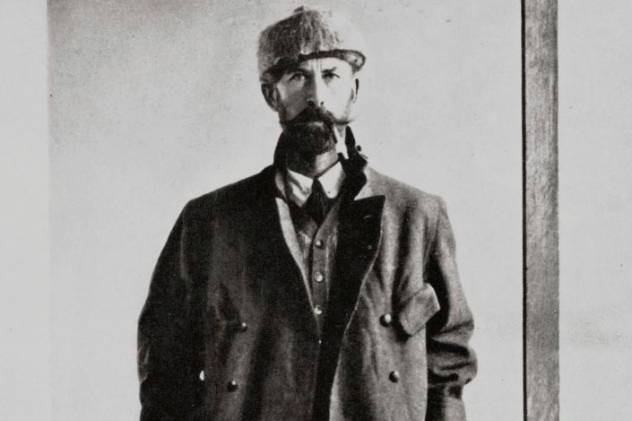

10 Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews was a celebrated explorer for the American Museum of Natural History who famously explored the Gobi Desert using a fleet of Dodge cars. While there, Andrews and his team unearthed numerous complete skeletons of previously undocumented small and large dinosaurs, as well as the remains of several insect species and the bones of large mammals. In the 1920s and 1930s, Andrews’s exploits were celebrated in the world press. After retiring in the 1940s, Chapman became a popular writer of children’s books about dinosaurs. Andrews is also the man most commonly associated with Indiana Jones. Like Jones, Chapman was a lean yet muscular man who took to the field wearing a slouch hat and sporting a pistol. Andrews wasn’t afraid to use his weapon on occasion, and the books he wrote about his own travels in China and elsewhere are littered with shoot-outs and fight scenes that would not be out of place in the pulp magazines of his day. Andrews said that in his life, the threat of death was an almost constant companion: In [my first] fifteen years [of field work] I can remember just ten times when I had really narrow escapes from death. Two were from drowning in typhoons, one was when our boat was charged by a wounded whale, once my wife and I were nearly eaten by wild dogs, once we were in great danger from fanatical lama priests, two were close calls when I fell over cliffs, once was nearly caught by a huge python, and twice I might have been killed by bandits. Like Indy, Andrews was a well-educated and gifted archaeologist who preferred action to cloistered study. The two also share a preference for revolvers and an antipathy for snakes. In regards to the latter, Jones has an irrational fear of snakes, while Andrews gained his loathing after vipers, who were fleeing the nighttime cold of the Gobi Desert, found their way into his camp. When they realized what was happening, Andrews and his team killed 47 highly venomous snakes in a fashion that Indiana Jones would have approved.

9 F.A. Mitchell-Hedges

Most Indiana Jones fans will agree that Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was disappointing. However, the story of the Mayan crystal skulls, which conspiracy theorists and dime-store Forteans believe supposedly foretell the end of the world, starts with a man worthy of Indiana Jones. Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges was an English traveler and writer who decided to seek a life of adventure instead of attending university or any other institution that would give him a reputable name. Beginning at a very early age, Mitchell-Hedges began exploring the Canadian wilderness, war-torn Mexico, and Central American coast in search of the lost city of Atlantis. Mitchell-Hedges wrote about his travels, and along with his wife Lilian-Dolly and his adopted daughter Anne Marie Le Guillon, Mitchell-Hedges became a celebrity during the height of adventure journalism. Mitchell-Hedges’s greatest find, the crystal “Skull of Doom,” is a point of controversy. For his part, Mitchell-Hedges claimed that he found the eerie skull in the 1930s. Anna refuted this and claimed that she was the one who had found the skull underneath a Mayan temple in British Honduras (modern-day Belize). Going even further, Anna claimed that a Mayan priest had previously used the skull to kill his enemies, while in the hands of nonbelievers, it brought bad luck. Whatever the true story, Mitchell-Hedges believed that the skull was evil, and its finding has become the source of many legends and silly predictions.

8 E. Hoffmann Price

Whereas Andrews has been mentioned as a real-life inspiration behind the creation of Indiana Jones on numerous occasions, E. Hoffmann Price has not. Oddly enough, Price not only lived a life worthy of Indiana Jones, but he also wrote the type of stories that inspired George Lucas and Steven Spielberg to create the character in the first place. Described by science fiction writer Jack Williamson as a “genuine solider of fortune,” Price was a California-born graduate of West Point, a veteran of three combat tours (the Pancho Villa Expedition, the Philippines, and World War I), and a well-traveled fencer and boxer who happened to be interested in archaeology, Arabic, and what was then called “Oriental studies.” At some point, Price settled down into a steady job in New Orleans, but he maintained his adventuresome spirit through his fiction. From the 1920s until his death in 1988, Price composed thousands of short stories that spanned several genres, from action-adventure to strange horror stories that were frequently printed by the seminal pulp magazine Weird Tales. Price also has the distinction of being the only person to ever meet writers Robert E. Howard (the creator of Conan the Barbarian), Clark Ashton Smith, and H.P. Lovecraft face-to-face. In particular, Lovecraft and Price maintained a close friendship until Lovecraft’s untimely death in 1937. The pair even collaborated on a short story called “Through the Gates of the Silver Key.” Some of the characters that Price created which may have influenced the creation of Indiana Jones include the Singaporean detective Pawang Ali, Jim Kane (an American guerrilla fighter in the Philippines), and the French swordsman Pierre D’Artois, who often fought evil cult groups like the one Indy faces in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

7 Frederick Russell Burnham

Called “He Who Sees in the Dark,” Frederick Russell Burnham was a US scout and Native American tracker who made a name for himself in Africa as a British spy and adventurer. If he truly helped to inspire Indiana Jones, then Indy would be the second fictional character touched by his larger-than-life legacy. The first was Allan Quartermain, H. Rider Haggard’s heroic big game hunter. (On a stranger note, if history had gone in a different direction, Burnham would be better known as one of the two men who first introduced hippopotamus meat into the Western diet.) Armed with his trusty six-shooter, Lee-Metford rifle, and various indigenous weapons, Burnham became one of the most feared and respected scouts in North America and Africa. In the US, Burnham fought with the Army in the Southwest during the Apache Wars. In Africa, he participated in both the Matabele Wars, which helped to win what became known as Rhodesia for the British South Africa Company. Burnham also fought in the bloody Second Boer War, where he frequently worked behind the lines doing covert operations such as dynamiting Boer infrastructure. Burnham’s exploits in Africa (which include the assassination of Mlimo, the Matabele spiritual leader who fomented the rebellion that helped to spark the Second Matabele War, and his leadership of the feared Lovat Scouts, a Highlander regiment in the British Army) helped to make him one Great Britain’s biggest heroes. Outside of war, Burnham made his mark in other arenas. Besides partaking in the Klondike Gold Rush, Burnham also found time to help found the modern Boy Scouts along with Robert Baden-Powell, whom he had met during the Second Matabele War. While in Mexico with celebrated fisherman Charles Frederick Holder, Burnham uncovered a large, inscribed stone in the Yaqui River Valley that has since come to be known as the Esperanza Stone. The stone, with its bizarre symbols and unknown origin, remains a favorite topic of discussion among Forteans, or the followers of paranormal researcher Charles Fort, who examined the stone as part of his The Book of the Damned.

6 Giovanni Battista Belzoni

Giovanni Battista Belzoni was literally a giant of his age. Standing somewhere around 201 centimeters (6’7″), the Italian-born Belzoni first made a name for himself as a circus strongman in England. Belzoni, almost certainly a polymath, was an accomplished hydraulic engineer who built engines for exhibitions. It was this skill which brought Belzoni to the attention of Muhammad Ali Pasha, the ethnically Albanian former commander in the Ottoman Army who helped to establish modern Egypt. In 1815, Belzoni journeyed to Egypt in order to show the Egyptian ruler his hydraulic irrigation machines, but the Italian strongman and engineer wound up becoming one of Egypt’s great plunderers, ransacking many ancient tombs and temples. What Belzoni managed to accomplish in Egypt is astounding. In 1816, Belzoni, using his great strength and skills as an engineer, retrieved a 7-ton bust of Ramesses II from his mortuary temple at Thebes and sold it to the British Museum, where it still stands today. Next, Belzoni and a team of workers cleared the entrance leading to the great temple at Abu Simbel and entered the site. Belzoni would continue to explore the insides of Egyptian tombs, such as the burial chamber of Seti I, which is still occasionally called “Belzoni’s Tomb.” Belzoni also became the first modern man to set foot inside of the Great Pyramid of Giza. For many archaeologists, Belzoni, who helped to popularize Ancient Egyptian artifacts in Great Britain before dying of dysentery in West Africa, is more of a grave robber than a scientist or academic. Funnily enough, the same charge has been lobbed at Indiana Jones.

5 John Pendlebury

Although an archaeologist by trade and education, John Pendlebury was more of a swashbuckler than anything else. With his distinctive look, which included a glass eye that he received after an early childhood accident, Pendlebury typified the daring British gentleman-adventurer of the early 20th century. Even before entering Pembroke College, Cambridge, Pendlebury was a dedicated classics scholar with an interest in Egyptology. Not long after graduating, Pendlebury became involved in excavations at Akhenaten’s capital of Amarna in Egypt and at Knossos in Crete, which was being overseen at the time by famous British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. By age 25, Pendlebury was already the curator at Knossos and the director of excavations at Tell el-Amarna. Though Ancient Egypt was his first love, Pendlebury made his working home in Crete, where he studied Minoan culture and its ties to the greater Mediterranean world. For years, Pendlebury worked as something of a freelance archaeologist on the island and grew to know every inch of Crete, from the mountains to the coastline. This knowledge would serve him well during World War II, when as a commissioned officer in the British Intelligence Corps, Pendlebury helped to lead local resistance against the German invasion in 1941. Based in the city of Heraklion, Pendlebury and Cretan guerrillas bravely fought against German paratroopers until Pendlebury was wounded by Luftwaffe machine guns. Pendlebury was captured by the Germans, had his wounds dressed, and was then executed and buried outside the Canea Gate. Like the later Indiana Jones, Pendlebury became a hero of anti-Nazi resistance to both local Cretans and Allied intelligence service.

4 Percy Fawcett

The most common belief is that Fawcett was murdered and cannibalized by a local tribe. However, some uncovered evidence may point to the fact that Fawcett intentionally got lost so that he could go about creating his “Grand Scheme,” a secret commune practicing a strange, cultish religion dedicated to theosophy and his own son Jack. Theosophy, which influenced some of the more bizarre aspects of Nazi ideology, is an esoteric philosophy that was incredibly popular among well-heeled individuals during the 1920s. If Fawcett was indeed influenced by theosophy and the desire to create his own religion, then the story of his disappearance would make for an Indiana Jones movie.

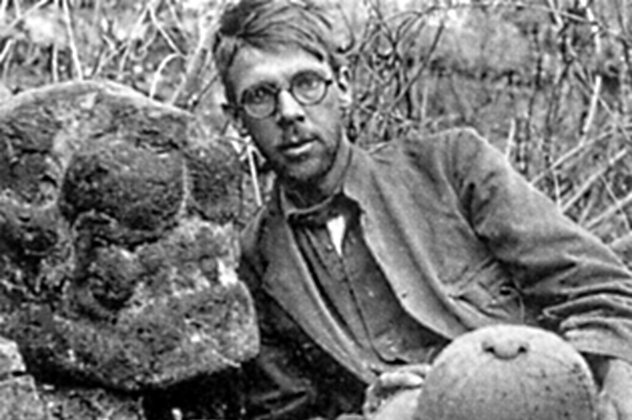

3 Sylvanus Morley

Even though he looked like the typical “egghead” professor, Sylvanus Morley, an American archaeologist for the School of American Archaeology, was capable of brave feats, especially as a spy in Central America for the Office of Naval Intelligence during World War I. Morley, who was an expert on the Native American cultures of the Southwest, first began exploring Mexico in the early 20th century. His interest was the Mayan civilization, and in 1912, he began excavating the city of Chichen Itza. Here, Morley found his bliss, and in 1913, his plan to start fully excavating the ancient city was approved by the Carnegie Institution of Washington. World War I interrupted Morley’s plans, however, but the patriotic archaeologist decided to use his vast knowledge of Central America and his cover of a working archaeologist in order to spy on possible German naval activity south of the American border. Morley proved to be as good of a spy as he was an archaeologist, and even though he never managed to find any evidence that the Germans were hiding U-boat pens along the Central American coastline, he did manage to chart thousands of miles of terrain and even continued to file intelligence reports until 1922. Even before his death in 1948, Morley was regarded as one of the world’s finest Mesoamerican archaeologists.

2 Robert John Braidwood

Like his mentor James Henry Breasted, Robert John Braidwood was an archaeologist, a professor at the University of Chicago, and an expert on the ancient civilizations of the Middle East. Along with his wife and partner Linda, Dr. Braidwood helped to modernize the field of archaeology beginning in the 1940s. One of his most sensational finds was the village of Jarmo, a settlement at the foothills of the Zagros Mountains that began around 6800 BC. On top of this, while working in Turkey’s Amik Valley (then called the Amuq Plain), Braidwood became one of the first archaeologists to rigorously use Willard Libby’s process of carbon dating in order to ascertain the age of ancient artifacts. Although the very image of scholarly modesty, Braidwood did his part during World War II as the director of a meteorological mapping program for the US Army Air Corps. After graduating from the University of Chicago in 1943 with a PhD, the newly minted Dr. Braidwood was hired by Chicago’s Oriental Institute and the Department of Anthropology, where he would remain until his retirement. Throughout his career, Braidwood specialized in particularly ancient and somewhat mysterious sites, such as the Neolithic city of Cayonu in modern-day Turkey, where it is speculated that human sacrifice was practiced. Although not as dashing or larger-than-life as many of the men who have been labeled “the real Indiana Jones,” Braidwood did oversee numerous archaeological digs in the Middle East during the Cold War years, when the Middle East was a battleground, both real and political, between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their competing allies.

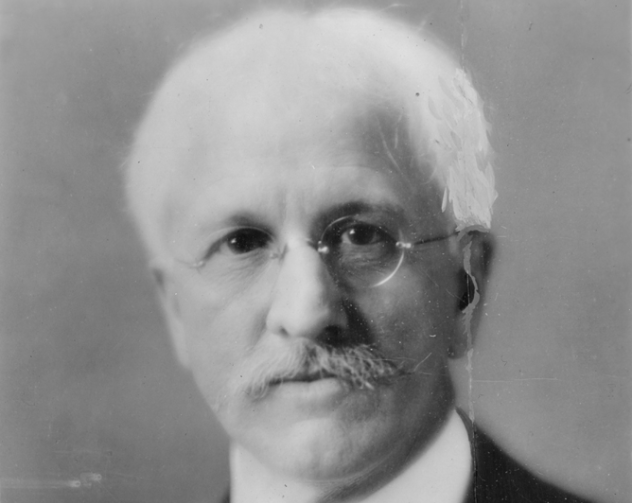

1 James Henry Breasted

James Henry Breasted remains a titan of archaeology. An Egyptologist who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago (which also has a connection with the character of Indiana Jones), Breasted is noted for founding the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, as well as coining the term “Fertile Crescent” as a way to describe the verdant splendor of the ancient Middle East. As the director of the University of Chicago’s Haskell Oriental Museum, Breasted contributed numerous artifacts from all over the Near East to the museum’s impressive collection. Breasted’s most famous excavation occurred in Egypt from 1922–23. There, he aided Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon in their efforts to unlock all the secrets of Tutankhamun’s tomb. This action places Breasted smack-dab in the middle of one of archaeology’s greatest urban legends—the curse of Tutankhamun. Breasted’s role in helping to unearth King Tut’s body not only provided fodder for the sensationalist press (which in turn helped to create films such as 1932’s The Mummy), but also started a craze for all things Ancient Egypt in Europe and North America. It’s safe to say that Breasted played a role in popularizing the idea of the glamorous archaeologist, and even though he lacked the often heedless enthusiasm that so many of us associate with Indiana Jones, he did contribute greatly to the field and even to Sigmund Freud’s understanding of religion. Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, VICE, Metal Injection, and others. His currently blogs at literarytrebuchet.blogspot.com. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet