10The Mentor’s Cargo

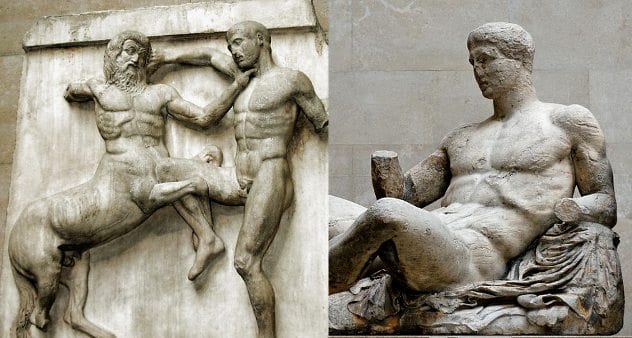

A case of sticky fingers is still being disputed between Greece and Britain. In 1801, Lord Elgin filled 16 crates with marble art he removed from the Parthenon. The next year, the British ship Mentor sailed for London, carrying the loot (or rightful property, depending on one’s view) and Lord Elgin. Near the island of Kythera, it was scuttled by a storm. Shortly afterward, the crates were salvaged and their contents displayed in London’s British Museum. The 17 sculptures and 56 panels that once decorated the Parthenon remain at the heart of an ownership squabble between the two countries. More recently, archaeologists visited the 200-year-old shipwreck to see if it contained more artifacts. They were on the lookout for additional Parthenon marbles that might have been left behind, but the trip was also an attempt to confirm a rumor that Lord Elgin had taken other antiquities from Greece. The two-week survey proved that he did. Divers found a stone vessel and the handles of ancient Rhodian amphoras, some stamped, dating back to the third century B.C.

9Something Like Cheese

While bracing for battle in 1676, the royal warship Kronan accidentally sunk itself. The Swedish vessel swerved too suddenly and tilted deeply enough for seawater to rush in through the gun ports. Flooding was bad enough, but somehow gunpowder on board ignited, and the explosion sent 800 souls to the bottom of the Baltic. After the wreck’s rediscovery in 1980, over 20,000 artifacts were brought to the surface, including brain tissue belonging to the lost sailors. In 2016, Swedish scientists found a black tin jar sitting on the seabed. Inside was a stiff goo smelling of cheese and yeast. Without further testing, the smelly product cannot be identified with certainty. However, researchers are fairly confident it is a dairy product. Since it resembles Roquefort, a granular blue cheese, the favorite treat of mice seems to be the most likely candidate. The icy mud of the Baltic and the sealed container preserved the contents well. If it turns out to be 340-year-old cheese, it could enrich our understanding of what it was like to live on a 17th-century Swedish warship.

8The Encarnación’s Gifts

Archaeologists were searching for pirate Captain Henry Morgan’s lost fleet when they found the Encarnación. She was not treasure laden or well known, but it was still a rare find. In 2011, while scouting for the five pirate ships sunk in a storm, equipment detected metal near the Chagres River, Panama. The location was perfect for the Morgan vessels. Diving down to investigate, they found a merchant ship instead. What made her so precious was that she hailed from the 17th century, a time greatly lacking information about Spanish ships. Most remarkably, the Encarnación’s holds were full. What years and shipworm do not destroy, looters usually carry off. Despite sitting only 32 feet (10 meters) underwater, no dodgy characters ever found the boxes of swords, nails and metal seals that once secured cloth. The cargo allows a glimpse into a time when Spanish colonies were flourishing and needed more wares. Her well-preserved state is revealing how colony ships were built, including the use of granel. A permanent type of ballast mixed from sand, rocks, and lime, the Encarnación might help determine if granel originated from the Old or New World.

7The Arab Dhow

Almost 20 years ago, divers hunting for sea cucumbers between the Indonesian islands of Bangka and Belitung noticed ceramics stuck in coral. It turned out to be Southeast Asia’s biggest underwater archaeological discovery. Nearby was the wreck of an Arab dhow from the ninth century. It is the first Arab dhow found in these waters—and the wealthiest. It carried a massive cargo of over 60,000 handmade items from China. Hundreds of ink pots, jars, and identical Changsha tea bowls testified that Tang dynasty China, much like today, mass-produced goods for export. Some of the Changsha treasures are in brand new condition, something that has never been found before. The goods catered for a big market and were possibly made to order. Decorations included motifs from Buddhism and Islam. White and green pottery, sought after in Iran, was also included. So was the largest Tang gold cup on record. A silver artifact might reveal some of the stock’s purpose; the flask bears two mandarin ducks, signifying a harmonious marriage. Other ornate boxes also show animals in pairs, perhaps made as wedding gifts.

6Story of the São José

Many slave ships once sailed the seas. Even so, finding their wrecks is surprisingly difficult. In 2010, the Smithsonian followed a lead that one could be found off the coast of South Africa. A dramatic paper trail led researchers to the only slave ship ever found on which slaves had perished at sea. Portugal’s archives recorded the departure of one of its ships, the São José, from Lisbon in April 1794. She carried 1,500 blocks of iron ballast. Ballast is significant since it was used to counterbalance a living cargo’s weight. A document from Mozambique, dated December 22, 1794, described a black man sold to the São José, leaving no doubt about the ship’s purpose. A final harrowing record, from South African archives, was an inquest of the Captain who recounted his ship’s final moments. On the 27th of December, the São José came apart on reefs near the Cape of Good Hope. Of the 400 men and women kidnapped in Mozambique, about half survived, along with the crew. The wreck’s identity was confirmed when divers found shackles and iron ballast.

5The Columbus-Era Shipwreck

In 1503, near Oman, a storm destroyed two ships and their crews. One, the Esmerelda, delighted the British archaeologists who found her. Sinking in shallow waters assured the Portuguese vessel’s complete dismemberment, but thousands of artifacts dot the sand in the bay. The rarest find is a silver coin called an indio, of which only one other has ever been found. Initials engraved on stone cannonballs confirmed the ship’s captain was Vicente Sodre, an uncle of the famous explorer Vasco da Gama. A mysterious metal disc displays the emblem of Portugal’s King as well as the country’s coat of arms. Well crafted, it was clearly important, but nobody knows what it is. Experts are guessing it is part of an unknown navigational device. Despite delivering the rare and unknown, the significance of the Esmerelda lies not as much with the artifacts as her age. She is one of the earliest ships to be recovered from the time when Europe began exploring maritime routes as far as Asia. The Esmerelda sank a mere decade after Columbus found the New World in 1492.

4The Lahore Carpet

Texel Island, in the Wadden Sea, is a veritable ship graveyard. It was a busy stop-over for vessels leaving or heading towards Amsterdam. The lane was often marred by heavy-duty storms that pulled many sailors to the bottom of the sea. In 1642, the Royal English fleet navigated from Dover to the Netherlands when the weather got grumpy near Texel Island. One of a dozen ships lost that day was found near the island in 2014. Dubbed the Palmwood Wreck, she preserved something that does not usually survive 400 years in the ocean—a delicate carpet made from wool and silk. Decay was kept at bay because the wreck was entombed in sand. The rare textile was in pieces, but the rich flower and animal designs can still be seen clearly. To determine where it came from and when it was woven, art historians studied the carpet’s colors, patterns, and manufacturing techniques. They found that it was made sometime in the 17th century in Lahore, which today is Pakistan.

3Lady Kerr’s Dress

In addition to the carpet, the Palmwood Wreck turned up the most valuable maritime find in the Netherlands. A look at upper-class fashion dazzled researchers when they found a 400-year-old wardrobe belonging to an elite woman. Cloaks, bodices, and stockings in near-perfect condition were adorned with large amounts of silver and gold thread. The highlight was a plus-sized gown made of Japanese damask silk. Retrieving clothing from the 1600s after being underwater for centuries was remarkable, but a name would be even more so. Good detective work identified the owner—a middle-aged spy in the court of James I. There was no name tag on the elaborate garments, all made for a largely proportioned woman, but a letter pointed historians in the right direction. Written in 1642 by Princess Elizabeth Stuart, it mentions how the English Queen Henrietta lost her baggage ships and that her two ladies-in-waiting lost their wardrobe. The matronly style of the gown belonged to an older woman, and the oldest was 56-year-old Jean Kerr, Countess of Roxburghe and informant for Spain.

2Roman Eye Medicine

Most knowledge about ancient medicine comes from old writings. In 2004, archaeologists got the chance to hold the real deal in their hands. The remains of the Roman vessel, the Relitto del Pozzino, was found near the coast of Tuscany in the 1980s, but it was not until later that the 2,000-year-old ship gave up its prize—the location where a doctor’s chest once rested on the seafloor. The box was gone but wooden drug vials, a mortar, surgery hook, and tin containers remained. An x-ray of the latter found what appeared to be five round tablets inside one of the vessels. The flat, gray pills remained dry and intact thanks to the sealed capsule. This allowed an in-depth chemical analysis of what Romans used in medicine and possibly what malady the tablets were supposed to treat. The ingredients included starch, iron oxide, beeswax, and pine resin. This made scientists tentatively theorize about a possible eyewash or remedy. The Latin name for eyewash, collyrium, derives from the Greek for “small round loaves” which also fits the shape of the mystery medicine.

1Atlantis Ingots

In southern Sicily, near the coast of Gela, a ship sunk around 2,600 years ago. In 2015, marine archaeologists discovered two Corinthian helmets, a jar, and many lumps of a mysterious metal, known only from Greek mythology and Atlantean legends. Orichalcum was described as a precious red metal second only to gold, and Plato’s writings claimed that it was mined in Atlantis, and it coated nearly every surface of Poseidon’s temple. Recently, in February 2017, the same wreck produced 47 more ingots of the ancient alloy. Together with the 39 bars found two years earlier, the accumulated deposit is one of a kind, but regrettably not valuable. The alloy consists of up to 80 percent copper, 15-20 percent zinc, and smaller amounts of lead, nickel, and iron. Even so, it does not diminish the mystery that still shrouds the real age and origins of orichalcum. Little is known about the ship that returned the fabled metal to the world. It most likely came from Greece or Asia Minor. Researchers are pretty sure the destination was the opulent city of Gela and that the ingots were headed for the workshops specializing in sought-after ornaments. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages