10 The Helots’ Rebellion464–462 BC

It’s not clear where the helots (ancient Spartan slaves) came from, but they were most likely ancient Laconians and Messenians. They were eventually subjugated by the Spartans and were kept as slaves since at least the eighth century BC. However, a massive earthquake hit in 464 BC and killed an extremely large number of Spartans. Seeing an opportunity, the helots rebelled, fighting against their masters for two years. Eventually, the Spartans asked the Athenians for help, but they soon sent them home, fearing that the more democratically inclined Athenians might help free some of the helots. The rebellion was eventually crushed, and the helots were put under brutal restrictions until they were eventually freed—the Messenian helots in 370 BC and the Laconian helots in the second century BC.

9 The Red Eyebrow RebellionAD 17–27

In AD 17, floods had ravaged the provinces around China’s lower Yellow River, and many of the peasants began to form bandit groups in order to survive. Another reason for their rebellion was that many farmers had to become tenant farmers (people who have to pay to farm their own land) because they couldn’t pay back their creditors. Painting their faces with red war paint to resemble demons, they called themselves the Red Eyebrows and were quite successful in fighting off the forces sent by the Xin dynasty. (Ironically, Wang Mang, the ruling emperor, had usurped the throne from the Han dynasty.) A large army was sent to defeat them, which it did at first, until the Red Eyebrows crushed them in AD 23. Declaring a 14-year-old boy of the Han dynasty as emperor, they actually had to fight another rebel group, the Greenwood Army, in order to capture the throne. Liu Xiu, a different member of the Han dynasty, declared himself emperor and was able to defeat the Red Eyebrows. In a rare act of benevolence, Xiu offered extremely gentle conditions for surrender, which were quickly accepted.

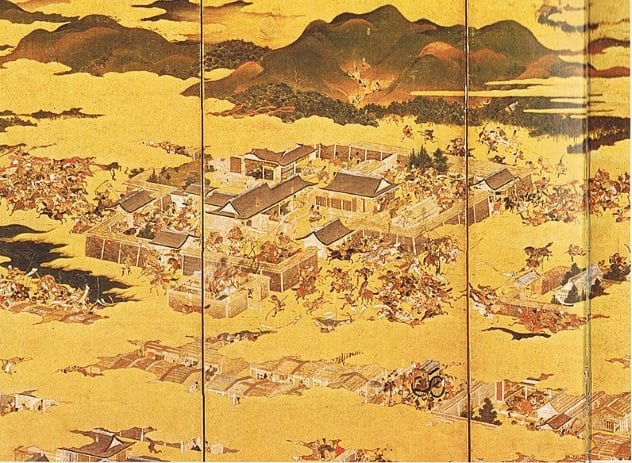

8 The Hogen Rebellion1156

After the death of Japanese emperor Konoe in 1155, a power struggle erupted, mainly between the former emperor Sutoku and his half-brother, the newly-appointed Emperor Goshirakawa. Angered at his loss of power, Sutoku allied himself with some other political enemies of the emperor, and they marched their army on Kyoto. On July 28, 1156, Sutoku and his forces arrived in the city and decided to wait until the next morning to begin their attack. However, Goshirakawa’s army decided to attack during the night, eventually repelling their enemy and forcing Sutoku to retreat. Many of the rebellion’s leaders were either killed in battle or executed shortly after, except for Sutoku, who was exiled. Many historians believe this was the first step in a series which culminated in the first samurai-led government in Japan’s history.

7 The Battle Of The Golden Spurs1302

In 1302, the peasants of Flanders (in present-day Belgium) rebelled against the French forces occupying their lands. As a larger force traveled from France under the command of Count Robert II of Artois, they butchered any civilians they came across, women and children included, which further angered the Flemish people. When the battle began on July 11, it seemed as if the French would be victorious, as their army of over 10,000 men was going up against a poorly armed local militia of about 8,000. However, the Flemish had prepared for this battle and had dug ditches and streams to hamper the movement of the French cavalry. Count Robert II led the infantry and would have won the battle had he not retreated to allow the cavalry to finish the job. When most of them were butchered by the Flemish, the count tried to repel their attack but was unsuccessful. He was later killed in the battle. The battle gets its name because of the spurs which the Flemish took from the dead Frenchmen. It was also the first example of how infantry could easily defeat cavalry and set a precedent for future battles during the Middle Ages. In the end, the French would defeat Flanders in their war, allowing the county to remain independent but not without paying a substantial financial cost.

6 The Cornish Rebellion1497

Near the end of the 15th century, poverty was rampant in Cornwall, especially among tin workers and other laborers. When Henry VII became king, he wished to fight the Scottish, who were terrorizing the border and amassing an army. In order to fund the potential war, he instituted a new tax, which was too much for the people of Cornwall. Led by Michael Joseph, a blacksmith, and Thomas Flamank, a lawyer, the Cornish people raised an army of 15,000 men and marched on London, remaining almost completely nonviolent. (They did kill a tax collector in Taunton.) When they reached present-day Deptford, they were met by the king’s army. Outnumbered nearly two to one, the poorly trained Cornish army fought bravely, but the English army thoroughly defeated them, killing up to 2,000 men and capturing Joseph and Flamank. The two leaders were hanged, drawn, and quartered, and their heads were placed on pikes on London Bridge to serve as a warning. (Being hung first meant they were granted the “king’s mercy.”) As punishment, Henry VII imposed even harsher taxes on the Cornish as well as a series of fines.

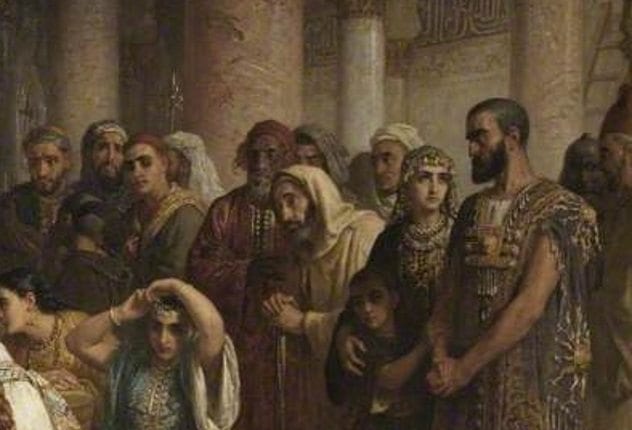

5 The Morisco Revolt1568–1571

Also known as the Rebellion of the Alpujarras, the Morisco Revolt was an uprising by the Moors of Spain. Angered by a series of laws restricting their faith, language, and clothing, the ex-Muslims of Granada rebelled. When it first began, the army was only 4,000-strong, but by 1570, over 25,000 soldiers fought against King Phillip II and his men, utilizing guerilla tactics against the Spanish forces. The Moors were led by Aben Humeya, who was assassinated by his troops and replaced by Aben Aboo, who suffered the exact same fate. More than 20,000 men were sent to fight the Moriscos, and the former Muslims were eventually defeated in 1571. As many as 80,000 were expelled from Spain in 1609 by King Phillip III.

4 Bacon’s Rebellion1676–1677

Fueled by dissent due to declining tobacco prices, a rising cost of living, and recent attacks by the Doeg and Susquehanaug tribes, Virginian settlers banded together to rebel against the governor, Sir William Berkeley. (The Susquehanaug were also attacked because the settlers thought they were behind earlier attacks, which were really perpetrated by the Doeg.) Led by Nathaniel Bacon, the ragtag army looted loyalist properties and burned the capital building. The rebellion would have likely continued for some time had Bacon not mysteriously and suddenly died in October 1676, leaving behind a disorganized mess of rebels who continued fighting until the following year. Troops from England were eventually dispatched, but they didn’t arrive until after the rebellion was over.

3 Dos De Mayo Uprising1808

On May 2, 1808, Napoleon’s army had been occupying Madrid since March and had tricked King Fernando VII into abdicating. He was replaced with Napoleon’s brother, Joseph. Madrid had 55,000 French soldiers stationed, and they were needed when the civilians rose up, thinking the French were going to kill the royal family. After a few hours of vicious urban fighting, the rebellion was crushed, mostly owing to the military superiority enjoyed by the French army. Desperate to display complete control, Joaquim Murat, the French marshal, issued a decree stating that any person with a weapon would be shot. A number of other strict measures were enforced, leading to the execution of hundreds of prisoners. Due to the severity of the French response, Spain unified against their occupiers, driving the French out in the Peninsular War.

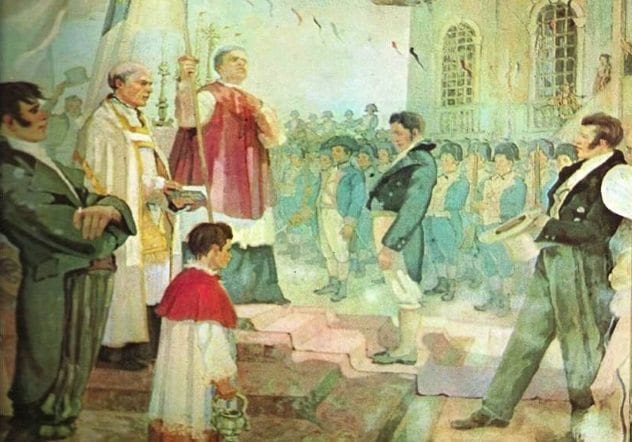

2 Pernambucan Revolt1817

Fed up with Portuguese rule, the people of Brazil temporarily formed a country known as Pernambuco. Located in Northeastern Brazil, it was home to many low-wage workers, who struggled under the taxes imposed by the monarchy. They marched on the capital and even managed to take it over. They declared that they had founded an independent nation, going so far as to come up with their own flag. However, the whole thing was crushed fairly quickly, and the leaders were executed. In total, the revolution only lasted 74 days. To try to prevent similar rebellions, the Portuguese cut the rebels’ heads and hands off and dragged their corpses to the cemetery with horses.

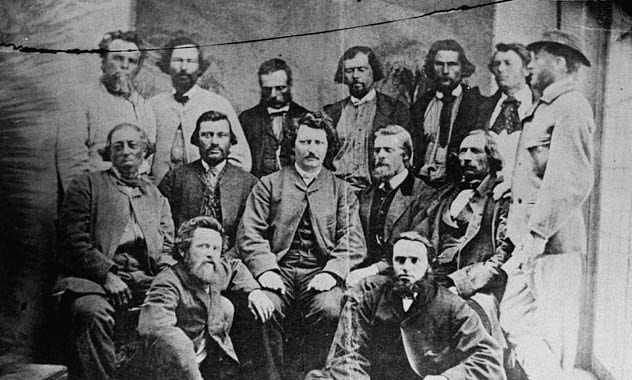

1 The Red River Rebellion1869–1870

The Metis people of Canada’s Red River Colony were worried about their land rights when Canadian annexationist William McDougall was appointed as the territory’s first lieutenant governor. (They had already been at odds with the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had been running the colony.) When the government began doling out parcels of native Metis land, Louis Riel, a Metis himself, organized his people into a fighting force and fought against the Canadian government, seizing Fort Garry, outside of Winnipeg. Riel fled before he could be captured. A treaty was drawn up, which created the province of Manitoba and was supposed to grant land to the Metis people. But it was mismanaged, and the Metis settled further west, where they again fought against the government in the North-West Rebellion, also led by Riel. This time, he was captured and executed.